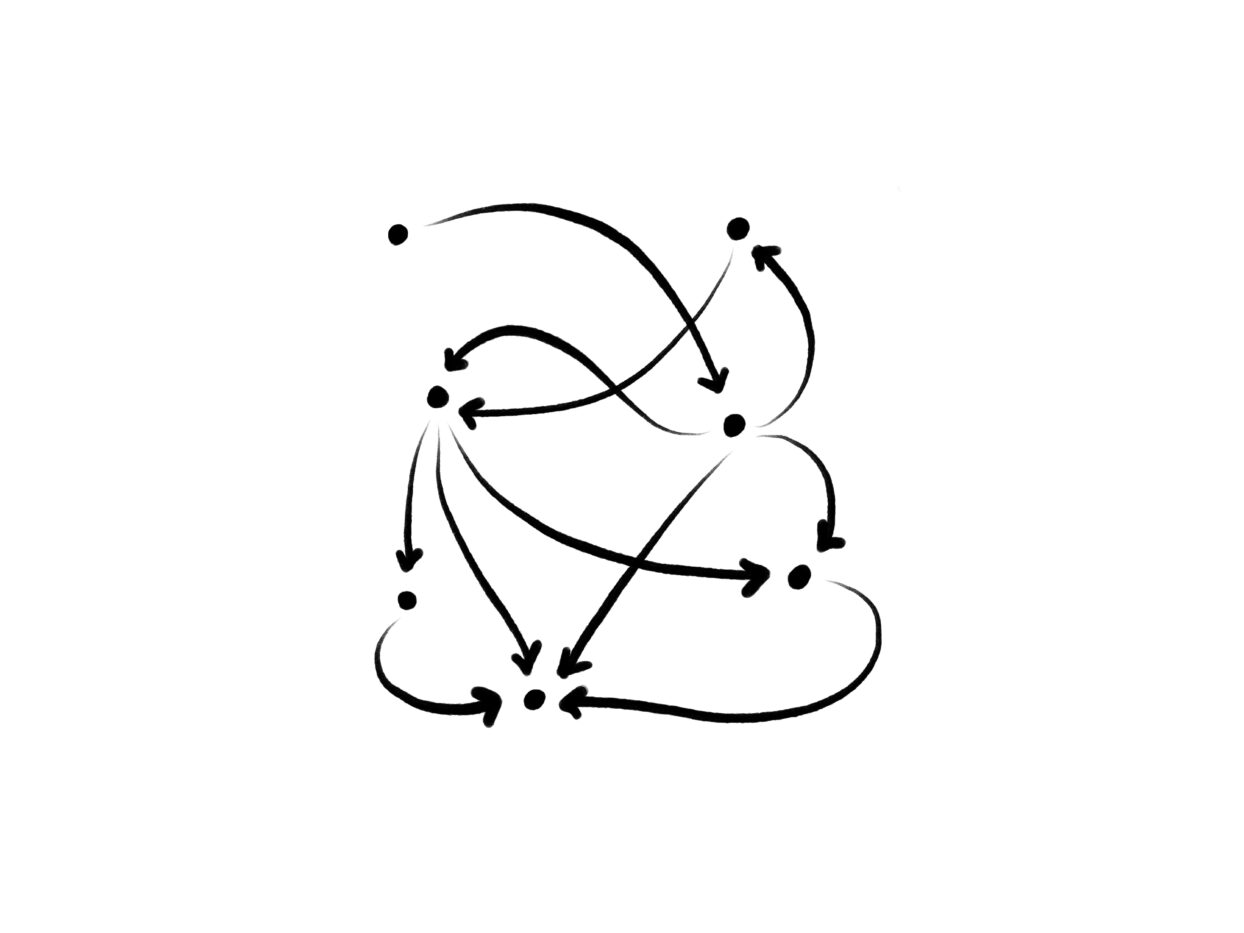

Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

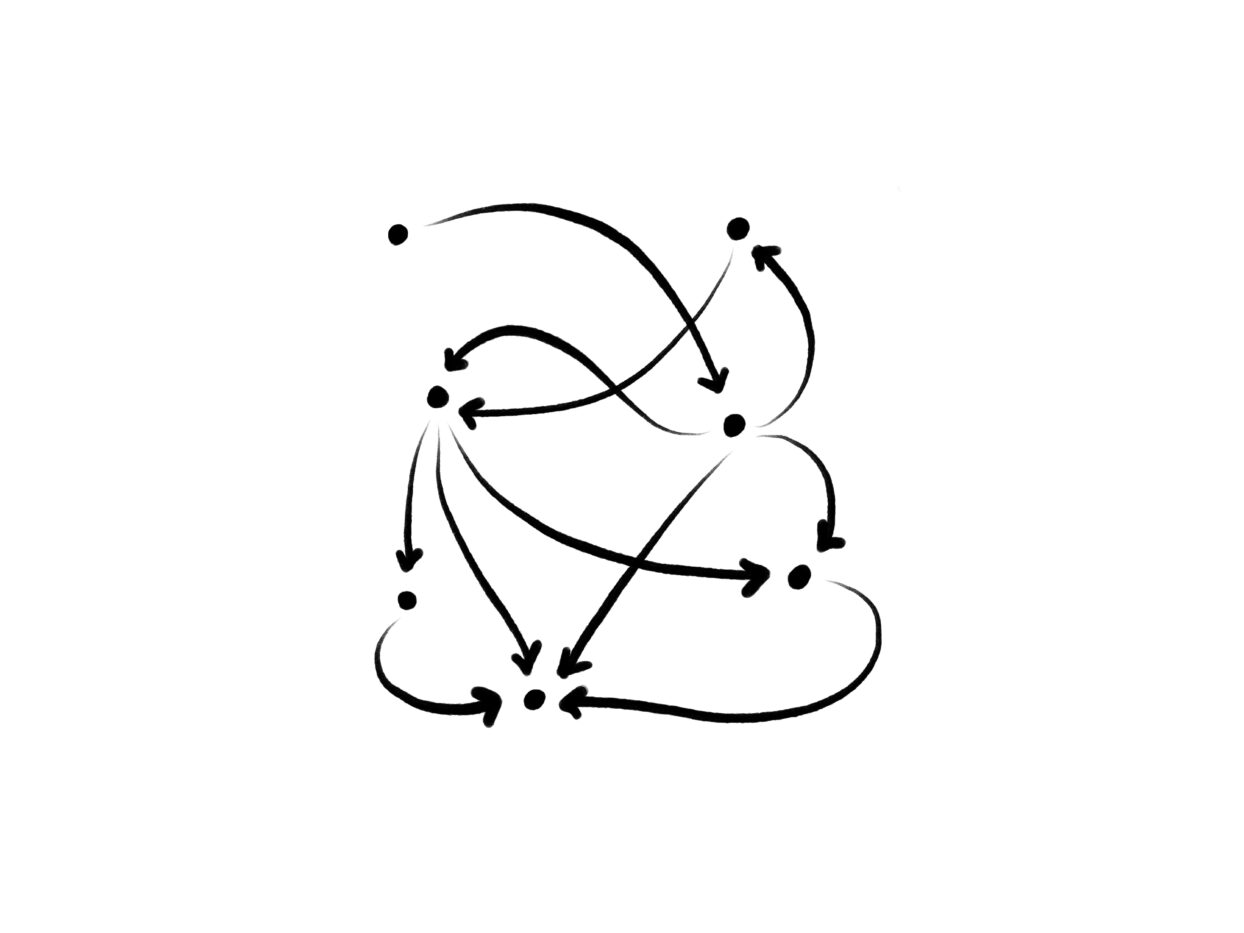

Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

Since the outbreak of war in Sudan in April 2023, nearly thirteen million people have been internally displaced and prices in Darfur have soared. In El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur, basic food items cost more than eight times what they do in other parts of the country. In the mountains of South Kordofan, people resort to boiling grass and leaves to feed their children; in El Fasher, people survive on animal feed and animal hide, bartering smuggled rations. Fields once lined with sesame, groundnuts, and sorghum lie fallow. According to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, which is produced by an international consortium including the U.N., nearly 25 million Sudanese are now trapped in “acute food insecurity.”

Starvation in Sudan is not the result of drought, or bad luck, or even the chaos of war. Both the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) — Sudan’s national army — and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) — which evolved from the Janjaweed militia responsible for the Darfur genocide of the early 2000s — have learned that hunger kills more quietly than bombs and more efficiently than bullets. Even before the fall of El Fasher to the RSF in late October, traders were priced out at internal checkpoints by its “taxation” requirements. The paramilitary had surrounded the city for over five hundred days, choking off aid. Both the RSF and the SAF have blocked trucks carrying aid from Chad, leaving millions in western Sudan without access to food or medicine. RSF units have seized World Food Programme warehouses, redistributing supplies to fighters and selling goods at extortionate rates on the black market. Meanwhile, the SAF’s Humanitarian Aid Commission buries cross-border shipments under mountains of paperwork, despite marginal aid delivery improvements in areas under its control. Convoys of food and medicine sit idle; trucks loaded with sorghum and lentils bake in the sun as bureaucrats debate permissions. Each side blames the other while civilians waste away.

When the warring parties use scarcity as a domination strategy, they draw from a playbook written by previous rulers of Sudan stretching back to the colonial era. Under Anglo-Egyptian control at the end of the nineteenth century, subsistence farming was deprioritized, and resources were directed away from Sudanese households and toward British cotton mills. The Gezira Scheme, established by the British in 1925 and often celebrated in development textbooks as one of the largest irrigation projects in the world, was in practice a vast mechanism of extraction, redirecting water for empire.

Post-independence governments and opposition forces have, unfortunately, inherited this legacy. Some academics argue that the government of modern Sudan began to weaponize hunger as early as its founding in 1955. During the Second Sudanese Civil War of 1983 to 2005, leaders in Khartoum privileged the Nile Valley and its elites, treating peripheral regions — Darfur, South Kordofan, Blue Nile, and what is now South Sudan — as hinterlands to be disciplined. When droughts and famines struck in the 1970s and 1980s, they were met with governmental indifference and even outright manipulation. An estimated 250,000 people died of hunger between 1983 and 1985. The government under President Jaafar Al Nimeiri delayed acknowledgment of the crisis and blocked aid in order to consolidate power; the opposition forces of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement did the same in regions under their control. Beginning in 1989, the military dictatorship punished political dissent in the South and in the Nuba Mountains with starvation. Humanitarian corridors were closed, grain supplies were diverted, and the SAF bombarded farmlands.

International humanitarian law, codified in the Geneva Conventions and Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, prohibits the starvation of civilians as a method of warfare, yet enforcement is negligible. Although the ICC has jurisdiction over Darfur, indictments proceed at a glacial pace. Without consequences, warring factions can continue to restrict food access with impunity. The result in today’s Sudan is a grotesque deadlock: armies block food, civilians starve, aid agencies issue press releases, and the global system shrugs.

Geopolitical rivalries compound the problem. Western governments issue statements of concern but hesitate to confront regional partners like the United Arab Emirates, which has been accused of funneling arms to the RSF in exchange for gold. Meanwhile, Qatar, Turkey, Egypt, and Iran have supplied the SAF. China maintains its quiet stake in Sudan’s oil infrastructure, seemingly uninterested in humanitarian fallout despite directly or indirectly providing arms to both sides of the conflict. At the same time, aid agencies have softened criticisms of abuses for fear of losing their already minimal operating abilities and further endangering their staff. (By mid-2025, dozens of aid workers had been killed in Sudan, making it one of the most dangerous aid environments in the world.) Trapped between donor fatigue and the whims of armed actors, humanitarian organizations are incapable of providing a lasting solution.

In late October, the RSF committed ethnically motivated massacres, with bloodshed so severe it was seen on satellite images. The RSF dug mass graves while seizing El Fasher and burned bodies to hide the evidence. The militia’s control has intensified both the displacement and starvation of the city’s — and country’s — residents. The only durable response to Sudan’s famine lies with its civilians, who must be empowered to resist the militarization of hunger. Sudan’s land remains fertile; its farmers remain skilled. Until the SAF regained control of Gezira earlier this year, farmers in the region hid seed stock for the next season, even as the RSF stole their crops. In displacement camps, grassroots organizations continue to lead food distribution centers and community kitchens, provide medical assistance at Emergency Response Rooms, and negotiate emergency evacuations for those facing persecution by the RSF and SAF. What is missing is the stability that comes from foundational capacity-building. Emergency aid must be paired with investment in agriculture and infrastructure: seeds, irrigation systems, roads that connect harvests to markets. And grassroots organizers must be included in peace talks. Strengthening civil society groups — such as resistance committees, unions, and youth movements with deep community roots — offers the best chance of building a Sudan where food is not a weapon but a guarantee. Charity will not end the hunger in Sudan — only justice will.

Shahad Elfaki is a Sudanese-Canadian writer and organizer based in Toronto and Nairobi. She is a member of the Sudan Solidarity Collective, a volunteer collective based out of the University of Toronto, dedicated to resourcing grassroots civilian formations at the front lines of relief efforts in Sudan.