How should translators — or any writers, for that matter — respond to their critics? The usual advice is quiet dignity: for certain distances to be kept so that a sense, however slight, of superiority might be implied. Some even urge writers not to bother reading their critics at all, which is the literary equivalent of the sort of self-care that encourages melancholiacs not to watch the news, or check their bank accounts, or listen to sad songs. I, for one, prefer belligerence. Not just the clever letter to the editor or its modern incarnation, the complaint on social media, but the well-executed campaign of revenge. Lydia Davis’s example, in that regard, is inspirational. When André Aciman wrote a negative review of her translation of the first volume of Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu, faulting her for not capturing the rhythm of Proust’s French as well as her predecessors did, her response included: a snarky letter, which sparked a bitter exchange in The New York Review of Books; “The Walk,” a short story about a translator and a critic; and an essay, “Changing My Mind,” published twelve years later, explaining exactly what that short story was about.

Not only do these texts tell us that Aciman’s review was wrong, but also that he “liked talking about himself,” was a “small man,” a mischievous and pampered “youngest child,” now somewhat embittered, and used in his speech the very “empty rhetorical flourishes” that he admired in the older translation of the novel. Yet a third figure looms over Davis’s attacks, as indeed he haunts the introductions, prefaces, and accompanying chatter to just about every new or renewed translation of the Recherche. Davis confesses her frustration with him, as she does elsewhere, and repeatedly uses him as a cudgel with which to beat Aciman. I am talking about C.K. Scott Moncrieff, Proust’s first English-language translator, and the ghost Davis and all other subsequent translators have made a show of exorcizing from Proustiana.

Accounts of the life of Charles Kenneth Scott Moncrieff make him out to have been a rather combative critic in his own right. When he began translating Proust in the early 1920s, he was both an increasingly successful translator and an increasingly isolated figure in the London literary world. A running feud with the period’s preeminent literary careerists, the Sitwells, had solidified his aggressive reputation; scandalous rumors of his supposed seduction of the poet Wilfred Owen, spread after the latter’s death, had led former friends Robert Graves and Siegfried Sassoon to cut ties with him. An argument apparently broke out in an encounter with dour D.H. Lawrence, who later described Scott Moncrieff and his friends as “old queens bickering round a teapot.” He had by then relocated to Italy, officially as a writer and translator, though very much in the pay of the British intelligence service. Until his death in 1930, two days before Lawrence’s, he would regularly file reports on the Italian military build-up and the goings-on of fellow expats. He would also translate works by Stendhal and Luigi Pirandello, as well as all but one of the seven volumes of Marcel Proust’s novel — a feat no translator of Proust into English has matched since.

Not that any have tried, which is somewhat odd to point out given that five translations of various volumes of the Recherche have been published in the U.S. over the last two years: Swann in Love, by Lucy Raitz; Finding Time Again, by Ian Patterson; The Captive and The Fugitive, revised by William C. Carter from Scott Moncrieff’s original translation; Swann’s Way, by James Grieve; and The Swann Way, by Brian Nelson. While Raitz’s and Grieve’s are standalone volumes, the other three are part of competing cycles. Patterson’s edition finally ends the Penguin Proust sequence started by Lydia Davis in the early 2000s, whereas Nelson’s begins another, courtesy of Oxford University Press. Both of these series assign different translators to each volume, and a majority of the new translations feature notes or introductions that evoke and criticize Scott Moncrieff, less as a matter of course than in the manner of ritual ablutions. Acknowledging the shortcomings of his translations — for decades the only ones available, largely responsible for Proust’s success in the anglophone world — is understandably something of a prerequisite for producing new versions. Despite Scott Moncrieff’s evident talents as a writer, and in particular his ability to capture the flow of Proust’s famously flowing sentences, his work is said to misrepresent the original. His “sins,” as Davis calls them, are that he: heightens and pads Proust’s language; is squeamish about sex and sexuality; makes many mistakes and misreadings. Even new introductions to contemporary editions of the Scott Moncrieff translation largely echo these critiques, albeit emphasizing that he had to base his work on the original, error-filled French editions of the Recherche. Current editions are in fact reworkings of his translation, the most recent of which is Carter’s new scholarly edition; its fifth volume came out last year from Yale University Press. Carter follows Terence Kilmartin and D.J. Enright’s more famous double act, whose revisions, completed in the early nineties, are still for many the default English Proust.

Significant though they may be, Kilmartin and Enright’s touch-ups were not enough to convince Davis, who chides them where she can for introducing new errors of their own. Brian Nelson agrees, but feels the need to add that if Scott Moncrieff strays too far from the original, Davis sticks too close to it, “compromising her ability to write idiomatic English.” He proposes his version as the happy and true medium between the two. And so, as of this year, the anglophone reader looking to get into Proust will have to settle for one of at least six different versions, each with a claim to superiority over the others. The 21st century is the “age of retranslation,” to use the phrase translator and academic Isabelle Collombat coined in 2004; newly armed with an abundance of principles and methodologies, if not ideologies, translators are expected to challenge the works of their predecessors. The contest over Proust translations is indicative not just of a competitive enthusiasm for the author in the anglophone world, but of the state of translation in general: belabored, prone to retracing its steps, and frantically accounting for itself at every opportunity. Those looking for a point to the squabbling could do worse than blame a need for justifications, whether for the new translations themselves or for the investments of the publishers behind them. In the case of Proust, clearly, every generation will get the translations it deserves.

In Davis’s story “The Walk,” the translator and the critic, stand-ins for Davis and Aciman, meet at a conference in Oxford, where the latter gives a presentation on the “language of translation criticism.” He delights in causing other participants “discomfort and embarrassment” by using examples from reviews of their translations. (“Only one of them had received no bad reviews.”) Davis doesn’t say what the purpose of the presentation is, exactly, but it is clear that she is interested in contrasting the critic’s embattled solipsism with the translator’s general passivity, if not docility, which allows her to be attuned to her surroundings. The story’s centerpiece involves a direct comparison between Davis’s and Scott Moncrieff’s translations: competing versions of a Swann’s Way passage in each of their styles are quoted. The critic talks at length and “emphatically” about publishing; he is always somewhat lost in his surroundings, while the translator points out the sights, and knows the way home. She tries to show the critic how Proustian their evening is, but she cannot make him notice. The critic is always either stuck in the moment or in his thoughts. Only the translator connects their experience to literature.

I don’t think translation and criticism are as different as Davis makes them out to be. Within the pantheon of minor arts, the two share a similar status — each playful in its own way, each commanding the worship of a devoted, though largely aimless, sect. Translation begins as a critical interpretation of the text, reflected in a set of choices: what meaning or connections to bring out, what to elide. All bargains made in the knowledge that the exact constellation of sound and sense produced in one language can never be perfectly reproduced in another — which is merely another way of saying that a translation is an argument, an interpretation justifying itself, and as such exists at a certain remove from the original text. Her fictional translator may be passive, but Davis the author is not: she’s trying to make as much of a point as the critic in her story constantly is, as Aciman was when he reviewed her translation, indeed as she was when she translated Swann’s Way.

The critic Ryan Ruby calls ours the “golden age” of literary criticism, in which the critical essay is lauded — by critics — as an art form. No surprise, then, that this is also an age where literary translation is especially appreciated, however defensively, for its artistic merits. Nearly three years ago, the Booker-winning translator Jennifer Croft campaigned for publishers to include translators’ names on book covers, promoting the idea that translation is a creative act. Another award-winning translator, Susan Bernofsky, has long argued the same, calling translation “a form of storytelling”; the writer Kate Briggs describes it in terms like “speculative” and “novelistic” in her popular 2017 book-length essay on translation, This Little Art. Notions like these undergird the push for greater visibility of translation in general. Not only do translators, like critics, now have a community of self-promotion on social media, but the first quarter of the century has also seen the multiplication of book prizes and grants awarded specifically to translators (these are getting more and more particular, not only rewarding translations from specific languages, but also, increasingly, niche categories like “first translations” and “women in translation”), and the development of translation MFAs, as well as the rise of translation studies within academia. A recent issue of PMLA, the grand old journal of literary scholarship in America, theorizes the subject around its “cocreative powers,” and understands the “divergences” between translations and their prior texts not as failures but as “interpretive opportunities.”

This emphasis on creativity represents a wholesale shift from older persuasions, which cast translations as little more than replicas of foreign texts, with translators playing the part of dutiful pencil-pushers, laboring quietly in the shadows of superior artists. While the suggestions that translation and criticism are art forms in their own right are endearing, both proposals are endowed with the same limitations: criticism for criticism’s sake is as silly as translation for translation’s sake. The mischievous Sartre of What Is Literature? labeled critics “cemetery watchmen,” a phrase not unsuited to translators, particularly those going back over old imports. All criticism, no matter how impressionistic, is at heart concerned with that other artwork it is jealously looking after. So too does translation depend on the base reality of its source text. The abyss of questions and problems of translation, discussed here and there in their many pet names (“foreignization,” “domestication,” “untranslatability”) are at heart technical issues of faithfulness: of how smooth the English should read to adequately convey the original, of how far from literality the translation should stray to express its source, et cetera. Many questions are asked of translation in literary media, many more raised — by translators — on the translator’s ambiguous and selfless role between the texts. The answers, however, are few and oft repeated.

Comparing translations is first and foremost a technical matter. Never mind Proust’s aura, the fact that he has emerged as a unique cultural reference in the anglophone world. While the Recherche has become a reader’s rite of passage — a feat the literary-minded are encouraged to brave every few months in new articles and books that note the series’s length, or scope, or insights into love, art, and the passage of time — its translators can hardly even agree on titles. This happens to be a problem that Marcel himself weighed in on, soon after the publication of the first Scott Moncrieff translation, mere weeks before the novelist’s death. In an otherwise gracious letter to his translator, Proust objected to Scott Moncrieff’s choice of overall title, Remembrance of Things Past, a very loose translation of the French, lifted from Shakespeare’s Sonnet XXX. Contemporary consensus agrees with Proust, and all successive translations have opted for the more literal In Search of Lost Time, whose only fault is that it downplays, slightly, the double meaning of “temps perdu” as both “lost” and “wasted” time. A number of Scott Moncrieff’s other titles have also been revisited, most notably that of the fourth volume, translated today as Sodom and Gomorrah. Anxious to avoid obscenity charges, Scott Moncrieff called it Cities of the Plain; he enjoyed referring to it as “Cissies of the Plain” in his correspondence.

Proust also disapproved of the Englishing of Du côté de chez Swann (literally, “On the side of the home of Swann”), the title of the first volume, rendered by Scott Moncrieff and most others since as Swann’s Way. Proust took issue with what this phrasing adds to the original, since Swann’s “way” can also indicate Swann’s “manner” or “method.” Yet having to sidestep a preposition — “chez” (“at the home of,” which has no direct equivalent in English) — makes for a somewhat stilted literal translation. Vladimir Nabokov proposed “The Walk by Swann’s Place,” and no doubt inspired the British title for Davis’s translation, The Way by Swann’s, though not much else. Here, the new Oxford University Press series has nonetheless opted to make an intervention: Nelson’s translation bears the name The Swann Way, which is even more neglectful of Proust’s complaint. And the justifications evoked in the preface are unconvincing, to say the least. Nelson alludes to his title’s symmetry with the title of the third volume, The Guermantes Way, but omits to mention that this symmetry isn’t so perfect in the French, Le côté de Guermantes. Du côté de chez Swann is also much more straightforward than The Way by Swann’s or The Swann Way: one could imagine it employed in response to the question, “Where did he go?”, bawled at a bartender mopping his corner in some village in Normandy. Swann’s Way can function the same way as the original title does; it’s an attempt to match the tone of the French, if not its meaning, exactly. Other versions merely trade in the former for small gains in the latter. Whatever the creative act behind them, the translations are hemmed in by those two conflicting priorities. But exact translation remains elusive, regardless — those looking for an absolutely true reflection of the original are better off reading the original itself.

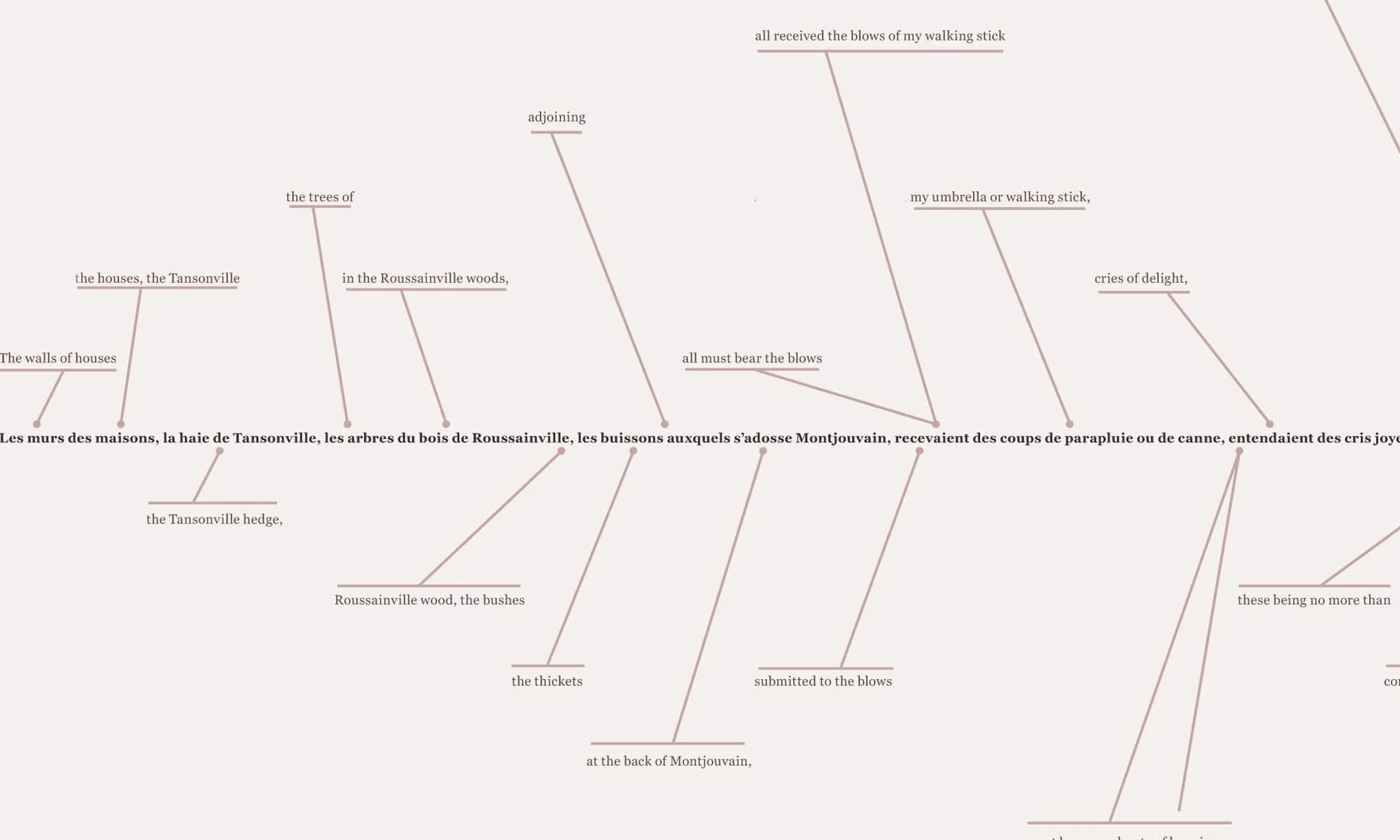

The first part of Swann’s Way reads like a compendium of the novel’s, and indeed some of twentieth-century literature’s, most famous scenes. A few involve madeleines and bedtime drama; more center on the narrator’s early, abortive aesthetic experiences, which serve as foundational set pieces for the enormous Künstlerroman that follows. These moments prepare the way for the novelist who will emerge in the final volume with ready-made theories of time, memory, and art, and a distinct desire to set them down in writing. Yet many of the key episodes end in failures of translation: the young narrator cannot, or cannot yet, find the right words to articulate the impressions that so trouble him. One early escapade sees him setting out for a walk, full of energy — over-agitated, even, after spending the whole morning reading. Scott Moncrieff’s translation, as revised by Kilmartin and Enright, goes as follows:

The walls of houses, the Tansonville hedge, the trees of Roussainville wood, the bushes adjoining Mountjouvain, all must bear the blows of my walking-stick or umbrella, must hear my shouts of happiness, these being no more than expressions of the confused ideas which exhilarated me, and which had not achieved the repose of enlightenment, preferring the pleasures of a lazy drift towards an immediate outlet rather than submit to a slow and difficult course of elucidation. Thus it is that most of our attempts to translate our innermost feelings do no more than relieve us of them by drawing them out in a blurred form which does not help us to identify them.

The typical Proustian sentence may not always conform to its caricature — that elongated, digressive monster, all hypotaxis and delayed grammatical closure — but it nonetheless tends to be marked by what we might call an impressionistic rhythm: it mimics a thought or an impression in the process of being formed. Before Kilmartin and Enright’s interventions, Scott Moncrieff’s versions of these sentences were structurally close to the French. It seems crucial, say, that in his translation, as in Proust, the first sentence ends on the “immediate outlet,” which Kilmartin and Enright place earlier. Likewise, they change the meaning of the second sentence, where the young narrator should be realizing that articulating his feelings does not necessarily “teach” him to “interpret” them (as Scott Moncrieff has it); in Kilmartin and Enright, only identification, rather than education or interpretation, is attempted. In other words, their revisions alternate cosmetic changes with significant corrections, not all of which are necessary or inspired. Though Davis largely follows Proust’s sentence structure, she cannot keep from the occasional flourish: where Kilmartin and Enright have “enlightenment” (from the simple “lumière”), she uses the odd phrase “light of understanding,” an example of precisely the kind of infelicitous elaborations that she criticizes Scott Moncrieff for.

The advantage is nonetheless with her translation, especially when considering Nelson’s ponderous construction, which introduces a needless repetition of “blows and cries” and leads the sentence to a whimperish end — “they would become clear,” a tonally inconsistent phrasing after the grand gestures that precede it. And yet, the most striking feature of Nelson’s version is in how closely it follows the choices of Scott Moncrieff’s revisers: the latter’s “course of elucidation” becomes Nelson’s “process of elucidation,” all for what in French is a straightforward “éclaircissement”; their “help us to identify them” becomes his “help us to understand them,” instead of Davis’s more apt “teach us to know them.” Both Nelson and the revisers employ the phrase “attempts to translate” for what the French would have as “prétendues traductions” (“alleged translations”). For all of his stated intentions, his is far less an alternative than another iteration of previous translations.

This passage culminates a few sentences later in a scene of mistranslation: a troubling aesthetic experience the narrator cannot, or cannot yet, put into words. To the sight of a pink reflection in a pond, in colorful dialogue with a recently cleared sky, his only response is the exclamation “Zut, zut, zut, zut.” The English language has no direct equivalent for this interjection. Both Davis and Scott Moncrieff transpose it into a sensible “damn.” Others overthink themselves into freak phrasings: Scott Moncrieff’s revisers change it into a silly “gosh,” Grieve into a sillier “dash it all,” and Nelson doesn’t bother translating it at all, save with a change in punctuation (“Zut! Zut! Zut! Zut!”).

It is a fantasy of immediacy Davis seems to subscribe to when she writes that, in Scott Moncrieff’s translation, “we do not see Proust clearly but rather through clouded glass; wrapped in scarves; lost in a forest.” Sure — but then what Proust wouldn’t be fogged up in the English language? Had we compared translations of another passage, they might have shown that Davis’s rhythms can sometimes be far less evocative than Proust’s or Scott Moncrieff’s, and that Nelson, at times (and to his occasional detriment), is clearly influenced by her choices, rather than those of the revised Scott Moncrieff. Davis may be interested in ridding us of those layers Scott Moncrieff wrapped around Marcel to keep him warm, but her interpretation of Proust’s style, which she calls “essentially natural and direct,” is no more clear-sighted than his — certainly not always an equally “natural and direct” English, as her own best work shows, in part because Proust’s supposedly plain prose is replete with understatement and intricate syntactical contortions.

Nor are any of the other translations paragons of transparency. They are simply other interpretations, bickering with the rest of them, if not with the disconcerting prospect of the many, many more that are sure to accumulate in years to come. Lucy Raitz’s translation is precise in terms of structure, less so with word choice. James Grieve, who translated both the first and second volumes (the latter for the Penguin cycle), is largely uninterested in keeping anything of the French rhythm or grammatical structure. He attempts instead to re-compose the original in what he posits to be a native English style, hoping that doing so might produce a true expression of the French. But by now the reader shouldn’t expect to be directed toward a flawless translation. Grieve’s is a Proust through broken glass; his feeling for English is simply not on par with Proust’s for French — and that may be what matters most, in the end.

In a review of Davis’s translation published in The Atlantic, Christopher Hitchens regrets that Nabokov never tried his hand at translating the Recherche. True, the Black Swan of Lac Léman was adequately multilingual, and in a definite poetic relationship with time and nostalgia. The young Nabokov of Speak, Memory is just as troubled by striking aesthetic experiences — shimmering post-storm sunlight, notably — as the young narrator of Swann’s Way is; both feel compelled to translate these experiences into language, “to transform them into something that can be turned over to the reader in printed characters to have him cope with the blessed shiver,” in Nabokov’s telling. But Hitchens’s remark disregards Nabokov’s own attempts at, and theories about, translation. These are marked by a certain pessimism, an unease about the inherent necessity of approximation. No translation of “zut” was likely to satisfy him.

Needless to say, Nabokov’s approach to translation has put him at odds with the field. Practitioners of the trade generally fall somewhere between two extremes: faced with the impossibility of exact translation, some smile at their condition, finding the gap between two languages to be artistically generative, every new translation revealing hitherto hidden facets of the original work. This is the area from which the likes of Kate Briggs and the practitioners of translation studies tend to operate. Nabokov is seated firmly on the opposite end of the spectrum, dwelling in the certainty of failure, mourning the impossible — and not a stone’s throw from the Renaissance cliché “traduttore, traditore” (“translator, traitor”). The introductory material to his Eugene Onegin seems at times anxious to remind that the translation is primarily for “students,” a crutch on which they should lean while they struggle their way toward the Russian text. The aim of his version is to teach the meaning of the original, and he has no sense that style, or form, is worth transposing if it distracts from this “literal ideal.” Only the Russian reader has access to the totality of the original work; the anglophone student must do without poetic language, and with lots of footnotes. When his translation was poorly reviewed, Nabokov did what he claimed never to have done over his novels, or poems, and fought back in print. His friendship with Edmund “Bunny” Wilson did not survive the scuffle.

Neither the Nabokovian position nor his Eugene Onegin was ever wholly approved of in the academic or literary mainstream, but his is more than just a frightening tale that translators inflict upon the disbelievers in their ranks. The most recent version of Nabokov’s argument has been promoted by Benjamin Moser (himself long engaged in the world of translation; he oversaw the Englishing of Clarice Lispector), not once but twice: most seriously in “Against Translation,” an essay published in Liberties three years ago, though most notably in a negative New York Times review of Briggs’s book, nasty enough to have occasioned a letter to the editors in her defense, cosigned by nine different translators including Davis, Bernofsky, and Emily Wilson. In both pieces, Moser expresses disappointment with the field as he finds it: with its perceived pretensions — he thinks translation is a “concrete,” rather than creative, art, if one at all — and moralizing self-promotion, by which the translation of foreign works is said to be “a positive good” in itself, and sold to the reader as self-improvement.

Claims that translated literature makes you “a better person” (per one Book Riot headline) are, it’s true, hard to avoid on the low-effort end of literary media, though they are at least easy to ignore. Higher brows on show in institutional and prize copy, or at various publications, usually make a virtue of the relationship between translation and diversity. This rhetoric is a particular target for Moser, who believes it betrays “an unearned and inherited ‘privilege,’” and as such is “a source of guilt — a moral affront, even, that accounted for the stridency which surrounded discussions of translation in the English-speaking world.” Whether that’s true or not, the case for diversity may be undeniably right so long as it remains abstract, but the point doesn’t stand up to the scrutiny of specifics, lest one attempt perilous connections between particular translated works and the “cultures” they are supposed to embody. Moser adds the odd suggestion that other literary cultures are largely inscrutable, and that English conversion can only cheapen them for easy consumption — producing token, contextless translations for the benefit of the tourist-reader. That may be true, again, but I wonder if the moralism pervasive in translation discourse is not better understood as the localized variety of a publishing-wide marketing scheme, wherein reading itself is conceived of in those terms. “Reading is good for you,” consumers are told with an air of desperation redolent of the academic humanities. The parallels are striking: publishers’ anxieties over literary fiction’s declining sales mirror those of humanities departments over shrinking budgets and reduced enrollment; the same concerns for cultural relevance lead to the same fretful defense of the social role of literature and the humanities education.

The peculiar positivity characterizing the discourse around literary translation has, I suspect, little to do with the American need, denounced by Moser, to devalue and absorb foreign literature. Translation is just unfortunate to be tied to literary and academic institutions that rely on it for legitimacy at a time when material pressures upon them are accentuated. Literary translators are still paid a pittance — no doubt even less, in relative terms, than they used to be decades ago. Perhaps this too explains why translators themselves militate for increased visibility: as a means of compensating for professional insecurity, or at the minimum mitigating it. At least creative writers have an increased sense of self-worth to fall back on, even as their work fails to give them a living.

Of course, Proust is still incapable of mustering the abundance of competing translations that older classics have amassed over the centuries. But why should translations be habitually updated? Should we demand that the classics themselves be rewritten every few years, too? One can almost make out an odd kind of suspicion lurking underneath this proposition, as if translation discourse were biting its tail. For all the celebration of the creative act, the push for constant retranslation betrays the belief that great translations are not possible — that the “timelessness” (for lack of a better word) of foreign classics do not carry over to their best English adaptations. The truth is the exact opposite: translation is certainly not a wholly creative act, but great translations do exist. They capture enough of the meaning and composition of their sources, and manage to express those quantities in English as intricate and poetic as the originals are in their own languages.

While the realization that a new English Homer is still being published every few years is, I find, rather distressing, at least the justification for this endless repetition has a pedagogical bent: a question of bringing the epics to contemporary audiences, rather than one of selling them on the truest rendition yet. (Within reason: Emily Wilson’s Homer and Davis’s Proust share a concern for the supposed lost simplicity of their source texts.) The newer Proust cycles, especially, tend to trade not on accessibility but on authenticity; each professes to be truer to the French than the last. Yet here both the Penguin and Oxford University Press sequences fall short on one important point. The greatest flaw of Davis’s version is, in a certain sense, that it is followed by the vastly different Grieve production. Theirs is a cycle that reads like a Recherche devoid of the consistency of Proust’s style — which some might argue is the novel’s only real source of consistency. After Nelson’s, the second Oxford volume will be provided by Charlotte Mandell, who has already published elegant renderings of minor Proust pieces, alongside major works by Mathias Énard and others; one can expect hers to be a different interpretation entirely.

This means Scott Moncrieff’s work still has continuity on its side, and it will remain so until some brave polyglot-poet translates the novel whole. Critics of Scott Moncrieff’s diction should also note that it is wholly consistent with the literary manners of the early-twentieth-century British upper class, whose equivalent in France is, after all, in large part the subject of Proust’s novel. The anglophone reader may be surprised to find that his version has certain stylistic similarities with late-period Henry James; these are no more objectionable than the use of iambic pentameter in Wilson’s adaptations of Homer’s dactylic hexameter. The decades of scholarship that are available to Scott Moncrieff’s successors does not always make up for the fact that they are not Proust’s contemporaries. Especially since historical concurrence is complemented by class and lifestyle correspondences, which imbue Scott Moncrieff’s rendering with an authenticity that few can match.

But no concern for authenticity, or textual quality of any sort, is enough to explain why new translations of the Recherche are, and will continue to be, published. I suspect the reasons there have less to do with artistic imperatives than with sales: heavily influenced by the academic market, sales of translated classics like Proust’s are comparable to those of the minor bestsellers in contemporary literary fiction. There is certainly incentive for Oxford University Press, as for Penguin two decades ago, to try to capture the market for itself. Behind the veil of critiques and arguments on authenticity, the contest for the English Proust is first and foremost a contest between publishers, jockeying for market share on academic syllabuses. If artistic concerns were truly at the heart of their calculations, then perhaps a book like Proust’s Contre Sainte-Beuve, translated once in the 1950s and hard to find ever since, would be the likelier candidate for a new translation. If not one of the many other French classics whose English renditions pale in comparison to their originals.

For now, Proust’s work is likely to remain the pretext for endless disputes among translators and critics. Davis’s story arrives at more or less the same conclusion. Many of the details evoked throughout “The Walk” are built on imagined distinctions, which the story dissolves as it progresses. This is especially true of the walk itself, whose unfamiliar return path surprises the duo — the critic most of all — by leading them right back to where they started. It is a variation on a scene from Swann’s Way, the same one Davis reproduces within the story in both her own and Scott Moncrieff’s translations, but also one of the more memorable conceits of Proust’s novel: the two directions available to the narrator for his childhood walks, “Swann’s” and the “Guermantes’s” way, are in truth connected — as is revealed in the sixth volume, the last Scott Moncrieff translated.

The story’s main point of contrast, though, is never overtly contested. Davis reserves its finest expression for the end, when the translator and the critic run into each other the next morning as they’re leaving town (and heading in the same direction, it turns out). “We will probably not meet again,” he tells her, and she believes it. The translator doesn’t realize it, just as she doesn’t make out the overwhelming similarities between the two translations of that Proust passage she quoted, but the logic of the story is clear. They will meet, inevitably — as will the other cemetery watchmen, future translators of the Recherche and their devoted critics, whenever the next publisher requires it. Thankfully, “The Walk” makes no attempt to show us what that might look like, so we don’t have to care.