We begin in a forest. The camera pushes through a clutch of trees to a clearing that reveals a drop into a ravine. “The owner of this watch has taken a hard fall,” Siri says. We’re listening in, apparently, on an automated 911 call on behalf of Bob B., who crashed while mountain biking and went unconscious. She provides “an estimated search radius of 41 meters” in her familiar clipped dialect — presumably saving the day. Although this is an ad for the Apple Watch, neither customer nor product is seen even once; we’re meant to assume that both are lying somewhere below our field of vision, the latter more active and alert than the former. The implication, underlined by a moody score, is that in a moment of crisis, technology can come to the rescue.

Through a growing focus on healthcare monitoring in recent years, Apple has positioned its wearables as essential accessories for the technophile and the casual hypochondriac alike. In another video called “Dear Apple,” users read letters addressed directly to Tim Cook, crediting their Apple Watches with saving their lives in various emergencies. Several are cardiac in nature, but others involve adventure-related injuries — falling through river ice, slipping on the job, confronting a bear. In some cases, the Watch’s specific health functions alert the user to medical issues, though the device also comes to the rescue simply by virtue of its function as an unlosable phone — a wrist-bound conduit to 911. By conflating crises looming inside the body with external menaces lying in wait, Apple pitches its Watch as the ultimate asset in a hazardous and uncertain world.

As a marketing strategy, fear works. When it launched in 2015, the long-hyped Apple Watch seemed like a failure: sales dropped 90 percent in just over two months following release, Fitbit was winning the wearables space, and even celebs were taking their Apple Watches off. (A Fast Companyarticle — headlined “Why the Apple Watch Is Flopping” — winkingly called out early endorsers like Beyoncé and Karl Lagerfeld for appearing to have ditched the accessories in a matter of weeks.) The tide turned when Apple marketers lit on the idea of branding the Watch as a way to ward off mortality, rather than just another symbol of ambient luxury. Though the first model featured a heart-rate tracker and fitness rings gamifying basic activities like standing and walking, Apple slowly increased its focus on health and fitness over subsequent releases, eventually introducing manual period tracking, an electrocardiogram (ECG) feature, glucose logging, and a redesigned Health app that could better integrate with other devices and third-party fitness apps. By late 2017, Apple Watch sales had surpassed those of Fitbit, and today, Apple owns about a third of the wearables market. In the process of securing its market dominance, the company has helped to turn obsessive physical monitoring from a niche hobby of the rich and fit into a commonplace ritual, with tens of millions of customers opting in.

But acclimating the public to the project of technological management of the body requires more than a few years of shrewd marketing. For decades, the American medical establishment has championed electronic medical devices as acceptable complements to, or even replacements for, more familiar treatment modalities, transforming yesterday’s harbingers of an impersonal cyborg future into today’s gold standard of “care.” And these devices have spawned a global industry with a market cap in the hundreds of billions. In the U.S. alone, millions — including me — live with electronic medical devices like retinal implants, insulin pumps, and pacemakers, relying on them for everything from improved sight to moment-to-moment survival. More than a million pacemakers are embedded worldwide each year, with some 200,000 in the U.S. Over 100,000 implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), battery-powered devices that can shock a heart out of irregular rhythms and prevent cardiac arrest, are inserted stateside every year, around half of the estimated global total. And one calculation puts the number of U.S. users of continuous glucose monitors at over two million.

It’s tempting to see constant self-monitoring as a way to avoid the worst pitfalls of the healthcare system. But as medical technology reaches beyond the very ill and into the realm of the ordinary consumer, companies like Apple and Google exploit both the logic and the deficiencies of professional healthcare in their efforts to bring everybody under their surveillance. Implantable devices embody the drawbacks of financialized healthcare, with medicine outsourced to private industry and placed in the hands of profit-motivated consumer-technology manufacturers. Meanwhile, manufacturers of these supposedly tightly regulated devices are allowed to behave like everyday tech companies — skirting accountability, dropping products without notice, leaving customers stranded — which should complicate our willingness to let existing tech companies move so seamlessly into the business of monitoring and treating our bodies. Rather than liberating us from the problems of the healthcare system, commercial wearables are furthering one of its central trends: the merging of patient and consumer into one compliant subject.

When Barbara Campbell was in her thirties, a genetic disease left her blind. In 2009, she became a “patient” of Second Sight, which manufactured a pioneering retinal implant called the Argus II. The implant was a wonder, helping Campbell regain a limited range of sight. But in 2013, Campbell was transferring between subways in New York City when the device failed without warning. “I was about to go down the stairs and all of a sudden, I heard a little ‘beep, beep, beep’ sound,” Campbell told the tech publication IEEE Spectrum. Second Sight tried to repair her device, but nothing came of its efforts. Not wanting to face the risks of an invasive surgery, Campbell chose to live with the broken implant in her left eye. Campbell lost her sight twice — first by illness, and then by mechanical failure. Since then, her body has been host to a piece of defunct technology.

She’s not alone. In 2019, Second Sight discontinued the Argus II, and the following year the company announced it would wind down operations completely. “No letter, email, or telephone call,” Ross Doerr, another Argus II patient, posted on Facebook. He heard the news from his stepson, who found out from a friend who’d come across the press release online. Doerr, who had been completely blind for decades, received the implant in 2019, only months before the product’s discontinuation. Around the time of Second Sight’s press release, he began experiencing severe vertigo — possibly related to the dizziness the implant sometimes caused — and his doctor recommended that he get an MRI to rule out a brain tumor. Like many electronic medical implants, MRIs can interact dangerously with Argus IIs, so MRI providers are supposed to contact Second Sight before patients undergo the procedure. But there was no one left to contact; the company didn’t answer Doerr’s calls, and it felt too risky to go forward with the scan without their sign-off. In July 2020, Doerr used his Facebook account to beg for “help in locating any doctor affiliated with Second Sight medical products in California.” He told IEEE Spectrum last year, “I still don’t know if I have a brain-stem tumor or not.”

Meanwhile, in July of 2022, Second Sight merged with California-based Nano Precision Medical, Inc. — a developer of subdermal drug-delivery implants which may eventually replace shots, and possibly oral medication as well — and reconstituted itself under the name Vivani Medical. It’s a familiar plot: a med-tech company appears boasting a grand proposal to conquer a new section of the body; a combination of press-generated enthusiasm and opaque science succeeds in attracting venture capital or boosting share prices; and sometimes there’s even enough money to buy smaller med-tech companies like Second Sight.

Elizabeth Holmes may have been sentenced to eleven years in prison for faking Theranos’s blood test method — and only because she defrauded investors; charges that she defrauded patients didn’t stick — but her style of posturing doesn’t seem to be disappearing anytime soon. In a recent demonstration about his brain-implant company Neuralink, Elon Musk described the implantation procedure as “like replacing a piece of your skull with a smartwatch.” But the event was mostly a recruitment gambit, Musk admitted, and so far Neuralink has only invented a more expensive way to kill macaques. (Still, he insists the product will be ready for human trials this year.) Sometimes, this Barnumesque approach to scientific development yields genuine advancement, but often it seems to siphon attention and resources away from more functional, less sexy approaches to the problem of illness — root-cause investigations, preventive medicine, and social and environmental mitigation. In the case of Second Sight’s merger, a flashy pitch and the subsequent influx of money swallowed an already-approved technology and spat out its customers. For now, Argus II patients remain physically hostage to defunct technology from a company that — legally, at least — no longer exists.

Medical-device manufacturers have swept a significant history of failures, injuries, overprescription, and misuse under the rug. They claim that downsides are minimal and problems rare, but recently, FDA recalls of medical devices as a category have soared — by 150 percent between 2003 and 2021, according to reports from Medical Design and Outsourcing and the FDA’s own Center for Devices and Radiological Health. In the past two years, the three leading manufacturers have needed to issue Class I recalls (the most serious kind) for some twenty models of pacemakers and other heart implants, which caused at least 188 injuries. Each of the recalls, which together comprised over 900,000 individual devices, raises the possibility of more harm beyond the reported data. Despite these figures, manufacturers manage to put their thumbs on the scale. A 2020 study found that 96 percent of first-time ICD and cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator patients received devices from doctors who had been paid by at least one manufacturer. Researchers have also concluded that informational materials given to candidates for left ventricular assist devices (LVADs), implants that can extend the lives of people with heart failure, were biased — no big surprise — in favor of implanting; patients were far less likely to agree to implantation when they were asked about the possible quality-of-life tradeoffs it could entail.

While devices can get patients out of the hospital in the short term, they can also impose an extreme, often lifelong dependence on the broader healthcare system. Cardiac devices require surgical replacement every five to ten years (opening the patient up to potential infections, mistakes, and future diseases) in addition to the far more frequent required checkups. Doctors might argue that for a patient with serious health troubles, intermittent checkups and surgeries are a reasonable price to pay for a prolonged life. Yet the imperative to extend life at all costs can encourage practitioners to bypass half measures in favor of more extreme or invasive ones, while minimizing potential side effects, complications, and quality-of-life concerns. As the Second Sight case shows, when devices fail, there is often nowhere to turn. Commercial manufacturers are for-profit companies, and they can go out of business or discontinue support for a particular device at any moment.

Even when companies don’t flame out, they are not always held accountable for harm and malfunction. In the 2008 Supreme Court decision Riegel v. Medtronic, Inc., the court voted eight to one in favor of the medical-device company Medtronic after a married couple sued because a balloon catheter burst during the husband’s angioplasty — setting a precedent that makes it difficult to sue manufacturers of medical devices that, like pacemakers, ICDs, and the Argus II, have undergone FDA premarket approval. And, historically, FDA oversight has been both fragmentary and late: the agency didn’t begin regulating medical devices until almost two decades after the first pacemakers were implanted. Increasingly advanced tech products are being implanted in our bodies — as instruments of healing, but also as tools of profit — and our legal and regulatory systems have still not caught up. Manufacturers may call implantees “patients,” but our pedestrian vulnerability to the whims of capital betrays our true status as customers.

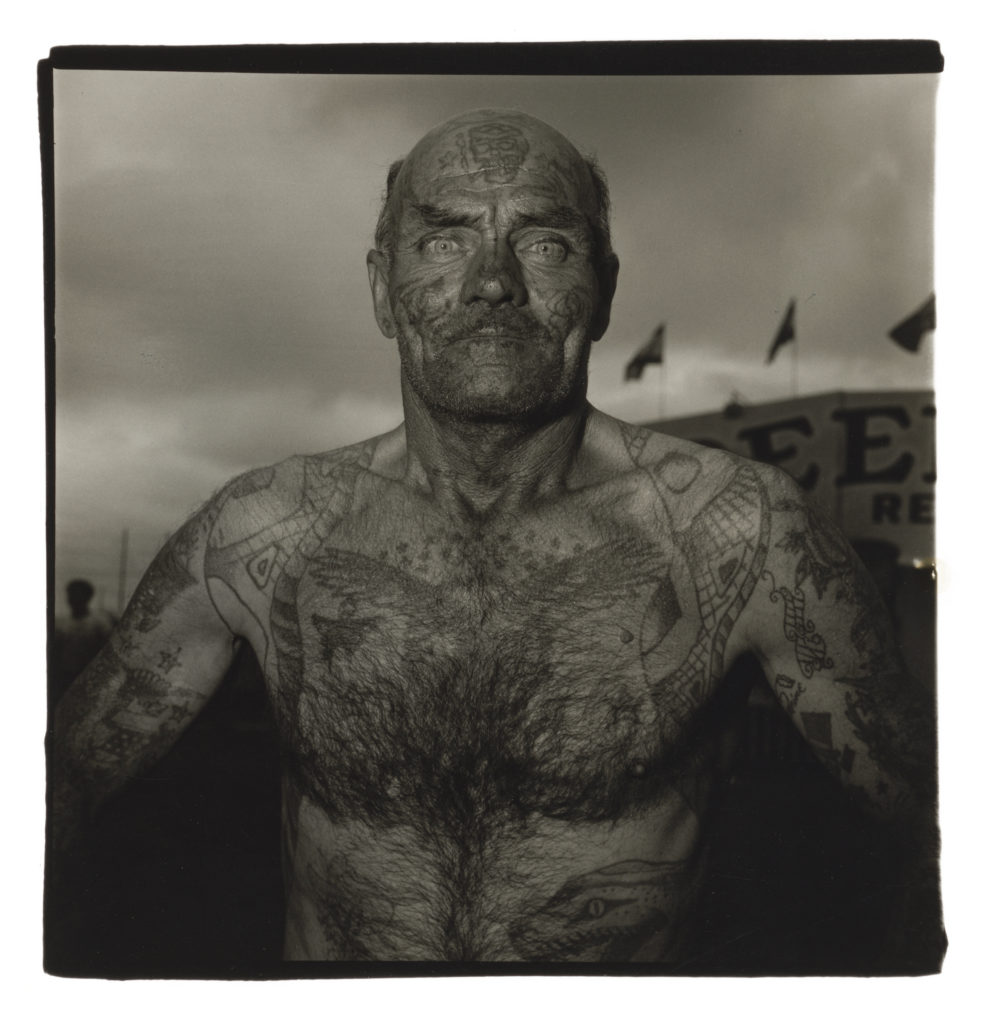

Implantable medical devices are, we’re told, conduits to unprecedented levels of personal freedom. Marketing materials feature Rockwellian photography of life in motion: customers play tennis, jump rope, attend work and school, mingle with friends, and play with children and grandchildren. A Medtronic pacemaker brochure promises, “Together, helping you lead a fuller life.” Another company’s materials assure us that the ICD is “THE PATH TO YOUR BEST POSSIBLE LIFE.” Almost never is a person pictured in a hospital setting or with any visible sign of the devices themselves, and steps like diagnosis, surgery, and follow-up appointments are conveniently absent. Every medical device arrives in a patient’s body after complicated processes of negotiation among device makers, hospital systems, and insurance companies, but doctors often downplay the variance between different brands. Whether a patient receives a device from company A or company B may seem like a small concern — until complications, like the one I experienced in June 2005, intrude.

I was about to turn twelve and had been living with my first pacemaker, installed to treat a sluggish heart rate, for a little over two years when my mother received a voicemail with an urgent message: on a home interrogation (the clinical term for a hardware examination), my device had shown an alarming lack of battery. My pacemaker was now in “end-of-life mode,” meaning that if it was not replaced soon, it would shut down permanently. The Guidant pacemaker had been meant to last an additional three years; at the time, my doctors told us that it was failing because it had been poorly installed. They’d had trouble finding space on my scar-knotted heart to fit the connecting electrodes, and, per their theory, my pacemaker was forced to work inordinately hard to deliver treatment, overtaxing its battery. Weeks later, in August 2005, my surgeon replaced my Guidant pacemaker with a Medtronic, just before the machine would have failed. Over the past nineteen years, I’ve undergone six surgeries for device upkeep and implantation, and in 2017 I switched from a pacemaker to my first ICD. Each successive implant brings the possibility of fresh complications, and during routine interrogations of this latest device, a new problem has emerged. One of the standard tests triggers a momentary gap in the algorithm, during which my heart is left on its own. For five to ten seconds, I am brought to the edge of unconsciousness, as my heart reverts to its naturally uneven and low pace — like a flyer in a trapeze routine, waiting to be caught by their partner before plummeting into an abyss.

Implant users may find themselves in free fall far more often than they’d expect. Clinical guidelines for ICD implantation have liberalized dramatically since the technology’s birth, leading to soaring usage rates. But studies have shown that as many as two-thirds of ICD customers do not receive so-called “appropriate therapy” in the first five years after implantation. To correct an irregular heartbeat (an arrhythmia), the device must deliver a shock at precisely the right moment; in one study, just a third of customers received any shocks at all, with about seven percent of the total sample experiencing both appropriate and inappropriate shocks, and nearly eleven percent of customers receiving shocks exclusively when they shouldn’t have. The authors of a paper in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences argue that “shocks have an arrhythmogenic effect,” meaning that a treatment intended to terminate arrhythmias may end up contributing to more of them. Though many ICD customers’ lives are saved, in other words, others might receive nothing but harm — and some might not need the devices at all. It’s possible that ICDs have become what cardiologists Bernard Lown — one of the inventors of the modern external defibrillator (and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize) — and Paul Axelrod feared when they co-wrote a 1972 op-ed in a journal of the American Heart Association warning against them: “an imperfect solution in search of a plausible and practical application.” Regarded without the rosy filter of marketing, cases where the devices work can begin to seem frighteningly dependent on good luck. The trapeze artists catch their partners cleanly every time — until the day that they don’t.

In March 2005, for instance, Joshua Oukrop, a 21-year-old man living with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a thickening of the heart muscle that can cause serious arrhythmias, was on vacation in Utah with his girlfriend. Since 2001, he had lived with a Guidant ICD. While the couple was mountain biking, Oukrop experienced what was likely a cardiac arrest, but due to an undiscovered glitch, his device failed to deliver a life-saving shock, and he died. Soon after his death, Oukrop’s doctors uncovered reports in the FDA’s database indicating that Guidant had known since 2002 that there were problems with its ICDs and continued to sell them anyway. Months before Oukrop’s death, the company had disclosed the issue (including reports of 26 “adverse events”) to the FDA, but no one had communicated the information to doctors, patients, or the general public. “The FDA should have been on top of this,” one of Oukrop’s cardiologists later told CBS News.

A hundred thousand Guidant defibrillators were recalled in the months after Oukrop’s death, but only because his physicians brought their findings to The New York Times. (A week before the Times published the story, Guidant’s chief medical officer sold $3.3 million in stock.) By the end of 2005, nearly 80 percent of the company’s active devices had either been recalled or were under a safety advisory, and the company had disclosed six additional customer deaths and many more documented device failures. (Lest his death sound like too much of an edge case, Oukrop’s brother — also an ICD customer — was subject to a separate recall of faulty electrodes that, according to manufacturer Medtronic, resulted in at least thirteen customer deaths.)

In 2011, the Justice Department fined Guidant nearly $300 million in criminal penalties, in what was reported to be the largest criminal decision against a medical-device manufacturer in U.S. history. (Not long after the 2005 recalls, the company had been acquired by Boston Scientific, which paid the tab.) Separate civil settlements of nearly $240 million were awarded to more than 8,000 customers in late 2007, before Riegel limited customer recourse. Citing Guidant’s own statements, Judge Donovan Frank wrote that medical devices “generally have a very high rate of reliability,” and, despite Guidant’s criminal obfuscation, device failures themselves were not evidence of criminal conduct. “Advances in medical technology have, unfortunately, inflated the public’s expectations,” Frank argued. According to this muddled logic, devices are mostly safe, but failure should come as no great surprise, since devices could never be entirely safe. Both makers and the press rehearse the line that, across all medical devices, less than one percent fail, but this data is difficult to verify, and accountability for manufacturers remains hard to come by. Citing Riegel in 2011, a U.S. district court judge threw out one of the many class-action patient lawsuits pertaining to the 2005-2006 Guidant recalls. It wasn’t until last year, while researching this essay, that I learned one of the final Guidant recalls included my own device.

The modern pacemaker is flush with bespoke features, allowing a doctor to calibrate a heart’s sensitivity to movement and even monitor it remotely. Today, most companies allow for data from pacemakers and ICDs to be sent directly to apps on doctors’ phones. Patients, meanwhile, are left in the dark, denied access to the medical information generated by their own bodies. Device manufacturers claim that customers in possession of medical information might not know what it means — and the FDA has agreed. In 2012, a spokesperson said, “In the current format, the data collected from implantable cardiac devices should be relayed through the physician to ensure proper interpretation and explanation.”

These restrictions may sound reasonable to the uninitiated, but, as a variety of patient activists have argued for years, allowing patient-customers to obtain the information on their own devices has the potential to significantly improve health outcomes and quality of life. Medical devices, like consumer electronics, come installed with factory settings, but each patient’s disease is specific and variable. Patients in possession of their own data can more intimately understand the relationship between their daily lives and their devices’ activities than their doctors (who typically spend only minutes with each patient every few months). Researchers have found that some forms of ICD misfires can be reduced by more accurate, customer-specific settings. And having some measure of control can alleviate the psychic burden — the powerlessness and uncertainty — of living with an implanted device. If bodily autonomy is truly a human right, disability and patient activists insist, then it extends to the management of medical devices. Manufacturers remain stubborn. As a Medtronic executive told The Wall Street Journal in 2012, “Our customers are physicians and hospitals.” That is, not patients.

The intransigence of manufacturers has spurred some customers to get creative. Hugo Campos, for instance, had been living with an ICD for four years when he and his husband lost their employer-provided insurance in 2011. Knowing he would be uninsurable due to his cardiac diagnosis and his device — the preexisting-condition provision of the Affordable Care Act wouldn’t take effect until 2014 — Campos decided to learn how to interrogate his own implant. “I was disillusioned. I thought, ‘Nobody’s looking out for me,’” he told me. “‘I can’t really trust the healthcare system. I have to take matters into my own hands.’” Campos traveled from his home in San Francisco to Greenville, South Carolina to attend a two-week cardiac-rhythm-management program. While there, he accessed his own device for the first time, capturing and reading its data just like a doctor would. He soon purchased a Medtronic programmer on eBay, along with an arsenal of decommissioned cardiac devices that he used to perfect his testing skills, and continued to self-monitor until his device was replaced in 2016. Throughout that period, he maintained intricate spreadsheets mapping interrogations and arrhythmias, trying to determine how certain lifestyle choices — everything from how much sleep he’d gotten to whether he’d consumed coffee — might have precipitated his episodes. He believes that his method has led to improvements in his health, while also allowing him to gain a degree of control over a system that had alienated him from his own body.

Other homegrown strategies have found wider application. In 2015, the married software designers Dana M. Lewis and Scott Leibrand created a free, open-source artificial pancreas project for the management of diabetes. Their tinkering began several years earlier, when they’d built an app to better customize the volume of the alarms on Lewis’s continuous glucose monitor, which were too quiet. Over time, the couple began adding more features, building in a predictive algorithm that could account for her daily activities and food intake. Their experiment worked: soon Lewis was spending more time “in range,” maintaining desirable glucose levels. By the end of 2014, Lewis and Leibrand had programmed what they now called the DIY Pancreas System (DIYPS) to funnel communication between her continuous glucose monitor and her insulin pump. In the years since the invention of the DIYPS, commercial versions of the same closed-loop system, known as automated insulin delivery, have become available. Still, Lewis and Leibrand have continued to share their work through OpenAPS, giving others the tools to build similar systems. The pair estimates that, as of July 2022, there were more than 2,700 OpenAPS users worldwide, and multiple small studies of self-reported outcomes among users have shown improvements in their health.

At first glance, commercial fitness tech looks like another way to surmount the barriers that prevent customers from managing their own medical devices. An Apple Watch can serve as the monitoring interface for OpenAPS. AliveCor and Apple Watch’s ECG functions can be used to check for arrhythmias when the data on an implanted cardiac device remains out of reach. Bringing in a personal device can, in fact, be a useful stopgap measure, a way to wrest back some agency from a dysfunctional healthcare system. But to reach their goals of continuous growth, companies like Apple are spreading their wearables far beyond those who really need them. They are normalizing commercial medical tech among the healthy — or those who may have considered themselves healthy at first.

Since Apple first began pivoting its Watch toward health and fitness applications, commercial wearable sales have grown skyward. The devices are currently used by a quarter of Americans, and market watchers expect the sector to expand more than threefold — from just over $52 billion in 2021 to $186 billion in 2030 — within a decade. The technology’s impressive sales record stems in part from its success in building habits in its users. Apple Watch functions become deeply integrated into wearers’ daily routines. Among the most ardent of these users are so-called “biohackers,” who monitor the ebbs and flows of their own bodies in attempts to optimize themselves like computers and delay death. For everyone else, these devices are pitched as something between frivolous wellness accessories and essential components of “preventive medicine.” (The two might even go hand in hand: your neuroticism could help you exercise your way clear of risk factors for disease.) Strategically, Apple seems to be trying to have it both ways, positioning itself as an alternative to the healthcare system even as it increasingly infiltrates it. This is, of course, a good way to maximize profit.

Many of Apple Watch’s loftiest promises depend on its ECG capability, a simplified version of a standard heart rhythm test that can find arrhythmias and other warning signs of sudden cardiac death. The Watch can periodically check the user’s pulse for signs of irregular heart rate; when notified, the user can then initiate the Watch’s ECG function to test for atrial fibrillation. The irregular rhythm monitoring is technically optional, but the software (and the advertising) encourages users to keep it enabled.

But if you’re healthy and young, should you? There are currently more than 100 million Apple Watch customers worldwide, and people aged 18 to 34 are, for now, buying more than any other age group. (Atrial fibrillation is most common in people over 65.) A 2018 statement by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force concluded there was insufficient evidence for the benefits of preventive ECG screening. Moreover, such screenings could be “associated with small to moderate harms, such as misdiagnosis, additional testing and invasive procedures, and overtreatment.” On its website, Apple touts FDA clearance for its ECG feature, but clearance is a process distinct from approval, which requires clinical trials and safety testing. Clearance, by contrast, can be granted to devices if they’re sufficiently similar to other, previously cleared products. Another rule allows manufacturers to alter components of existing devices without going through the hurdles of full approval; Medtronic was able to bring its faulty ICD electrode, the one that Joshua Oukrop’s brother had, to market without being required to complete new clinical trials. But all the nuances of the FDA’s endorsement gradations are easily elided in shrewd marketing, and companies can take advantage of the system’s opacity. What Apple usually fails to note when trumpeting its clearance is that the FDA also warned that the company’s ECG test “is not intended to replace traditional methods of diagnosis or treatment.” When the ECG function does identify an irregular rhythm, the Watch’s messaging encourages customers to seek further medical testing, potentially shuttling them towards the clinical cardiac realm and the prospect of future implantation. Some might see this as a positive, but there are profound risks attached to funneling ever more customers into a system so full of error.

Like any other medical device company, Apple pitches directly to physicians: “The future of healthcare is in your hands,” reads a banner on its public-facing healthcare website, above a photo of a doctor holding an iPad. The company is already promoting ways for doctors to use their products to improve performance inside hospitals, such as digitizing medical records via iPads and iPhones, and to extend their reach beyond it — say, by facilitating home surveillance for “at-risk” patients with Apple Watches. Apple is not offering an alternative to traditional med-tech manufacturers; its third-party developer platform is actively helping some of them with research and product development for things like portable ultrasounds and blood-loss measurement tools. And, of course, it is positioning iPads, iPhones, and Apple Watches as the natural interfaces for these new capabilities. This kind of expansion casts doubt on the utopian vision of a post-hospital future conjured up by so much of the industry’s marketing.

Apple is not the only tech behemoth getting into the health space. Amazon has its own fitness tracker, Halo, and recently acquired the private primary-care startup One Medical. Google bought Fitbit in 2021 (which had 29 million active users the year prior) as just one part of a multi-billion dollar investment into healthcare — including a slew of new research-and-development initiatives with hospital systems all over the country. Google also runs a health biotech company called Calico, which leads initiatives in anti-aging and extending human lifespans.

And other companies have emerged to capitalize on the demand for wearables. Whoop, valued at $3.6 billion, tracks a staggering number of signals from skin temperature and respiratory rate to heart-rate variability and sleep cycles, supposedly to improve the user’s fitness recovery and minimize strain. Levels, valued at $300 million, markets recreational glucose monitoring so that even non-diabetics can “unlock your metabolic health.” A smartwatch from the French company Withings supposedly checks oxygen saturation and detects sleep apnea; other Withings products, such as blood pressure cuffs, “smart scales,” and “sleep mats,” send their data to the watch.

With all this constant monitoring, it’s worth asking where the data goes and whom it serves. Flo, a popular period tracking company, was accused by the FTC in 2021 of sharing users’ personal health data with third-party analytics companies, making it available for targeted advertising. That the Apple Watch can now also track menstrual cycles via temperature sensing is a concerning fact in post-Roe America, given Apple’s track record of compliance with law enforcement and the push in anti-abortion states to prosecute abortions, miscarriages, and stillbirths by any means necessary. By its own disclosures, Apple complied with 90 percent of the law-enforcement requests for data that the company received in the first half of 2021, and, despite technically being medical information, the continuous streams of data collected by wearables aren’t protected by HIPAA.

All this data presents an opportunity for insurance companies. Many have devised partnership programs in which they give away cheap or free wearables to customers who agree to keep them on and exercise with a prescribed frequency. UnitedHealthcare has boasted that employers who opt in to its Apple Watch program may pay less in health-insurance costs, ostensibly because of improved health. But it’s not so hard to envision how wearables companies might capitalize on the willingness of customers to provide regular data on their health and fitness. “They’ve got a wealth of personal health data through Apple Watch,” Ben Wood, an analyst at the tech analytics firm CCS, told Forbes. “If they join some of the dots together [Apple] can become a very competitive health insurance player.” These sort of predictions, like the data wrung from a body, are endless and unreliable. But a good rule of thumb: when evangelists start envisioning the same future that skeptics fret over, take note.

For all the marketing bluster about improving healthcare access and outcomes, it’s difficult to see the expanding wearables market as anything other than an attempt to further privatize an already privatized system — turning customers into the host bodies through which capital flows and mutates. In an opaque, expensive, and often inadequate medical system, commercial health tech is able to market itself as an alternative — all while acclimating the public to round-the-clock body surveillance. Sickness and health may be quantifiable up to a point, and medical implants may be helpful for some, but constant self-monitoring can invite harm as much as prevent it. Arming ourselves with medical devices, we can lose sight of our bodies’ intuitive ability to self-monitor, to tell us when and if something is wrong; we can forget that doses of leisure and even risky pleasures can also add up to a good and healthy existence. When the mechanisms of care have lived behind a paywall for so long, surrendering to the consumer health-tech complex provides the illusion of control. Yet in trying to evade our own mortality, we instead devise solutions that remind us constantly of its boundaries. Nothing could be more human.