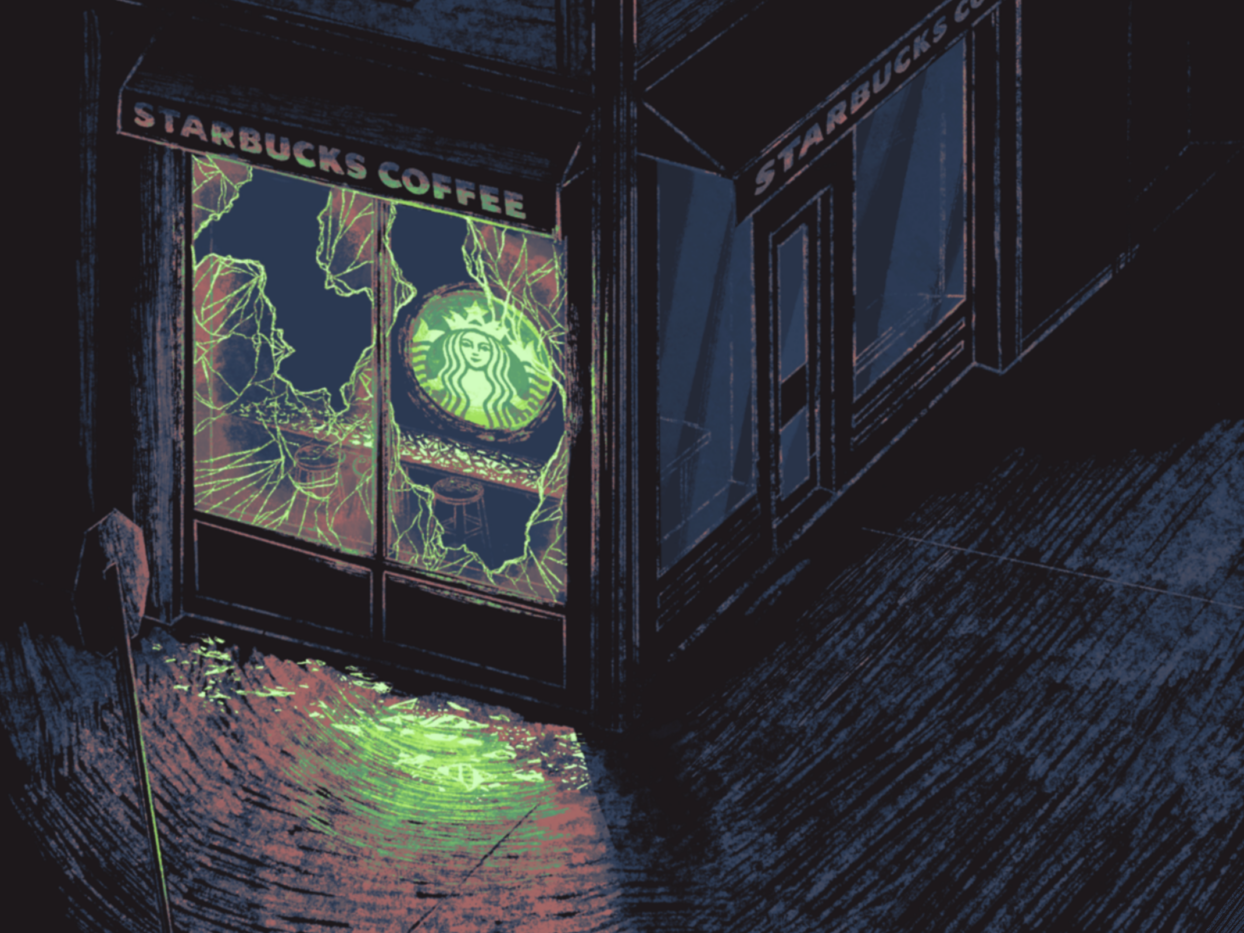

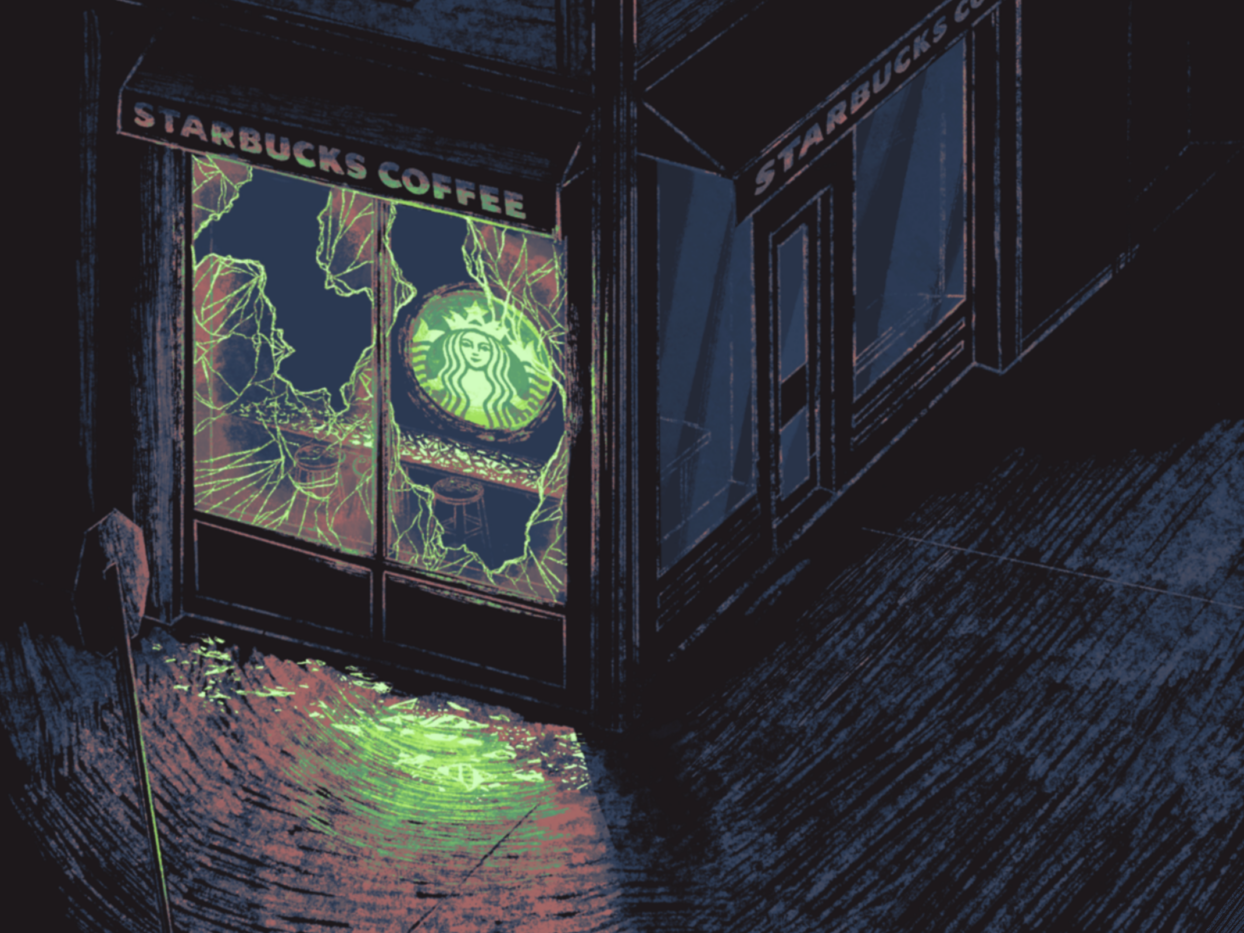

Image by John Kazior

Image by John Kazior

In May of 1985, following the Sandinista National Liberation Front’s final defeat of the Somoza regime, the Reagan administration imposed an embargo on Nicaragua. The White House paired this open economic aggression with more covert forms, channeling money and weapons to counterrevolutionary forces — Contra groups who counted industrial terrorism among their tactics, burning literal tons of product in raids on government-allied coffee cooperatives. This multifront attack made the Nicaraguan coffee industry a Cold War hotspot. Some members of the Third World solidarity movement in the North even volunteered as coffee “brigadistas,” flying down to pick beans in the mountains. To complete the circuit, a few dudes working for a food co-op warehouse near Boston began importing Nicaraguan beans from a Dutch roaster through a loophole in the embargo, selling them at a coffee shop they called Equal Exchange. Thus began the modern American ethical consumption movement.

The ethics of capitalist consumption have plagued us poor capitalist consumers for at least as long as that system has prevailed. In Capitalism and Slavery, Eric Williams detailed the moral appeals made by the original free-traders against the ghastly Caribbean sugar monopoly. Abolitionists in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century attempted to boycott goods produced by enslaved labor, agitating for “free produce.” In the twentieth century, the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union urged buyers to “look for the union label” in what became an iconic jingle. But over the past 40 years, as world capitalism shook off its last rival, bosses appropriated the idea of ethical consumption, too. These days, ethical impact is first and foremost a branding tool. Unwilling to compete on prices or quality in an era of globalization and commodity gluts, producers rely on advertising instead, and conscious marketing has become standard operating procedure, especially for direct-to-consumer brands that cut out the retail middlemen.

The triumph of Margaret Thatcher’s neoliberal slogan that “There is no alternative” (as in, to market policies and government austerity) — commonly known by the acronym TINA — has yielded a corresponding left-wing truism: “there is no ethical consumption under capitalism” or “TINECUC.” As a retort, TINECUC works on capitalists whether they’re using morality to hawk shoes or alleging hypocrisy when they see a communist holding an iPhone. And it works among fellow anti-capitalists who demand collective adherence to rarified purchasing patterns. If TINECUC, then there’s no ethical reason to forego a pandemic Hawaiian vacation or to buy the optional carbon offsets. As a result, most anti-capitalists currently understand consumption to be strictly personal: politicizing consumption only serves to marginalize leftists as picky eaters within mainstream society and welcomes capitalism’s salespeople at the same time. Better to insulate consumption from accountability than to set ourselves up to be played by marketers and bad-faith fellow leftists who see litigating consumption choices as an easy way to jockey for power, prestige, attention, or even money itself.

Adherence to TINECUC allows organizers to focus on building solidarity between workers or community members rather than buyers, whose common interests may be superficial. It is also, in a world system of production based on exploitation, a factually true statement, insofar as no purchase of anything made with exploited labor has any business branding itself “ethical.” But the unexamined phrase isn’t worth using; before people start attributing TINECUC to Marx or Lenin, we should figure out how Sandinista beans turned into Starbucks — and how anti-consumerist politics fell out of fashion on the American left.

It’s easy to see the politicization of coffee as the work of clever activists who then inspired even cleverer advertisers. But it’s not a coincidence that the battle centered on this product in particular. Beginning in the early ’40s, under FDR’s “Good Neighbor Policy,” the United States settled on a series of agreements with Latin American coffee-producing states. Seeking to undermine the appeal of fascism and communism in the Americas, the U.S. propped up the price of beans via planned export quotas. After World War II, the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) of 1962 established a sort of coffee OPEC, with exporting countries working with their importing counterparts. As a carrot to the nonaligned Third World, the Western bloc cooperated to keep prices high. But in the ’80s, with the Soviet project on its last legs and the United States opting for the stick over the carrot in Central America — e.g., the Contra war — the world’s biggest coffee consumer pulled out of the ICA and the country quotas ended. Bulk coffee prices collapsed, as did wages in the industry and, as a result, whole regional economies, foreshadowing free trade reforms to come.

By the time Equal Exchange came on the scene, then, coffee was already political: the Reagan administration used American coffee consumption as a weapon in the Cold War, the country’s citizens destroying the viability of socialist projects one cheap cup at a time. For coffee purveyors and their customers — especially at the left-wing shops that had been hubs for the anti-war movement during Vietnam — ethical consumption was a form of conscientious objection to America’s economic assault on the Third World.

In the ’90s, activists leveraged a consumer boycott of Folgers to pressure the right-wing government of El Salvador into a peaceful settlement of the country’s civil war. The boycott was led by the San Francisco-based peace group Neighbor to Neighbor, which was the brainchild of Fred Ross Jr., a second-generation organizer with the United Farm Workers. The UFW’s triumphant grape boycott of 1965-1970 provided the model, and Neighbor to Neighbor was able to enlist celebrities and politicians to promote the campaign –– especially Catholics, thanks to well-publicized Salvadoran military atrocities against church personnel. “Escalating the coffee boycott will reinforce the economic message we are sending to the right wing in El Salvador that they cannot with impunity undermine the efforts for a negotiated political settlement to the conflict there,” Neighbor to Neighbor’s local congresswoman, Nancy Pelosi, told the press in 1991.

Around the country, local solidarity groups organized to implement the boycott within their coffee communities. “Many area merchants, restaurants, and distributors have broken the death squad habit,” announced the Latin America Solidarity Committee of Ann Arbor, Michigan in a 1990 print advertisement, pointing to 21 local stores that had taken Folgers off the shelves. Neighbor to Neighbor’s labor roots ran deep, and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) heeded the boycott call, sealing off ports in California, Oregon, Washington, and Vancouver to Salvadoran coffee for nearly two years. The movement didn’t get Folgers to ditch murder beans, but it reduced U.S. consumption of Salvadoran coffee by a third and succeeded in putting pressure on the government through the big importers. After the signing of the Chapultepec Peace Accords in 1992, Neighbor to Neighbor ended the boycott, which is widely considered a winning campaign. The fluid movement between ethical consumption efforts and organized labor continued: one of the organization’s leaders, Rob Everts, joined Equal Exchange, soon rising to codirector. Fred Ross Jr. led a group of campaign veterans into the western cadres of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which has been at the forefront of low-wage labor organizing.

At the same moment, the reigning commodity brands were undergoing an identity crisis. In the spring of 1993, Marlboro cigarettes announced a significant price cut, which the markets took as a signal that even the strongest names would snap under globalized price competition. They called it “Marlboro Friday,” and, as Naomi Klein writes in her book No Logo, it heralded an emergency: “Study after study showed that baby boomers, blind to the alluring images of advertising and deaf to the empty promises of celebrity spokespersons, were breaking their lifelong brand loyalties and choosing to feed their families with private-label brands from the supermarket — claiming, heretically, that they couldn’t tell the difference.” These companies could no longer count on their buyers to pay a premium for labels; the only hope to avoid a race to the bottom was to win the attention of a growing cohort of younger consumers, one that marketing consultants named “Gen X.” No one did that better than an Italian clothing company called Benetton.

In the ’80s and ’90s, under creative director Oliviero Toscani, Benetton used its provocative ads to promote awareness of such social causes as world hunger and gay rights, as well as celebrate the new era of global integration and gender and racial equality. Toscani’s pictures harmoniously juxtaposed archetypical white, black, and Asian people, or to get at the same message, three similar human hearts labeled “white,” “black,” and “yellow.” One image showed a smooch between a priest and a nun, another a bunch of condoms. Some ads consisted of decontextualized, unlabeled scenes of violence from around the world. “The car bomb, the refugees, the dying man,” wrote Artforum editor Carol Squiers about the ads in 1992, “become the occasion to consider not the social and political relations that have caused the detonation, the flight, the death,” but the mundane security of new clothes. Benetton and the many brands that followed its lead weren’t operated by Third World solidarity activists, yet they bet on the appeal of a similar conscious, worldly vibe, one appreciated by Gen X customers. Pepsi successfully launched a redo of its ’60s “Pepsi Generation” ads, now declaring itself the drink of a “New Generation,” and up-and-coming Apple sold its Mac as the anti-IBM computer for thinking individuals.

The branding ended up being much more popular than the underlying politics, and this shift toward the post-Cold War youth market coalesced a decade later into what sociologist Keith Brown calls the “ethical turn” of the early ’00s. In his book Buying into Fair Trade: Culture, Morality, and Consumption, Brown describes this mainstreaming of ostensibly socially responsible brands that back their progressive branding with philanthropic programs or specific environmental benefits, including “fair-trade products, pink-ribbon-endorsed products, Newman’s Own line of food, hybrid cars, energy-efficient light bulbs, Product Red and other ‘green’ products.” In this unipolar environment, some American consumers felt (with good reason) like they were a little bit responsible for everything that happened in the world. The appeal of these ethical items reached beyond the original youth target demo: their accounts buoyed by expanding consumer credit, middle-aging liberals — including, by then, some of the eldest Gen Xers — paid extra to offset the spoils of Cold War victory.

Or at least they tried to. With the accession of China to the World Trade Organization in 2001, the suppression of nearly all the left-wing armed liberation movements, and the final emergence of planetary capitalism, it was rarer for progressive Americans to happen into authentic opportunities for solidarity. (If that sequence feels a tad rushed, that’s because it was.) Instead of using their coffee dollars to support socialist self-determination in Central America, U.S. consumers began participating in a sort of opt-in version of the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) via “fair trade,” buying from roasters that promised to voluntarily pay a stable, higher rate. These better beans bore the certification of the Fairtrade Labeling Organizations International (FLO) via its national affiliate, TransFair USA. But the goodwill of American consumers couldn’t substitute for the ICA, and “fair” coffee has only ever represented a tiny percentage of the market — not enough to support a way of life for farmers anywhere, though it has been a thin lifeline for some small cooperatives around the world.

As professional activists like Rob Everts struggled to find a place for themselves between ethical consumption and the burgeoning nonprofit industrial complex, a new, younger cohort attempted a withdrawal from the same systems. Punk and DIY ethics encouraged young people to eschew anything that was dirtied with capitalism: print your own ’zines by sharing the employee codes to copy shop machines, make your own music, get clothes from Goodwill or military surplus stores, consume as little as possible. These anarchists formed the hard core of the anti-globalization movement, shaped by and shaping in turn the post-Soviet conditions of disillusionment. They hopped from international summit to summit disrupting the meetings, smashing windows, and black bloc battling with police downstairs while capitalist flunkeys negotiated a new order of free-trade agreements and permanent Third World debt upstairs. The anarcho-propagandists of the CrimethInc. Ex-Workers Collective opened their 2001 handbook Days of War, Nights of Love with a one-page anti-ad warning that “THIS BOOK WILL NOT SAVE YOUR LIFE!”

Anti-consumerist tactics suggested by the popular tract include shoplifting, public sex, printing your own movie tickets, and forgoing deodorant. In this subculture, “freegans” who ate only free food — often “dumpstered” from wasteful grocery stores — took their ethical place ahead of consumerist vegetarians and vegans. Instead of using Benetton’s rainbow of colors to define their individuality, anarchists wore anti-individualist black, a smart choice when it came time for the police to file individual charges for property destruction, another favored tactic.

The preferred windows for smashing belonged to an emerging coffee chain, one that began in Seattle in the ’70s, became publicly traded in 1985, and benefited from the post-ICA collapse in bean prices. Starbucks quickly spread nationwide, joining a soft, vintage coffeehouse feel to the dual injunctions of branding and growth. During the ’90s, the chain jumped from around 100 stores to around 2,000. As part of its expansion plan, Starbucks targeted the small independent cafes that had been organizing hubs for the U.S. left, earning the ire of indie owners and their devoted customers. The anarchist antipathy for Starbucks solidified after the epic 1999 World Trade Organization protests in Seattle, where the locally headquartered company became a perfect punching bag for demonstrators’ ire. They left multiple locations smashed and looted.

Breaking a Starbucks window, the Crimethinking went, was a performative refusal of consumerism as the boundary of political action. “Don’t buy at Starbucks” was shopping; “smash Starbucks” was politics. Though their level of commitment varied from merely aesthetic to eco-terrorist, you could find a corner full of these punks in every American city and most of the suburbs.

There was insight in the anarchist intransigence: Starbucks had structural advantages over the independent shops, and well-meaning customers could hardly thwart the chain’s rise by making better purchases. Starbucks took that move too, bamboozling unsophisticated buyers with pictures of smiling coffee farmers. Facing down an adversary that refused to recognize any opposition, that claimed to unite us all beneath capitalism’s multicultural rainbow, the anarchists declined to play a rigged game, and they brought antagonism and the zero-sum nature of capitalist development to the fore at a time when many Americans imagined that a rising tide was lifting all boats.

Broken glass wasn’t going to halt the chain’s advance or stop the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, but neither was ethical consumerism, or for that matter, the largest street protest movement to that point in history. With the collapse of the Soviet project and the death by a thousand cuts of the Third World liberation movement, mere endurance was a serious challenge for anti-capitalists. In America, fighting back against Starbucks asserted the existence of a conflict in the first place. What these small anti-consumerist insurrections could and did do was preserve “hatred of capitalism,” a phrase the left-wing publisher Semiotext(e) used to title its pessimistic 2002 reader, which reflected on the previous period of political-ideological struggle, one they assumed was closed. The edited volume, which is heavy on French philosophers like Jean Baudrillard, Michel Foucault, and Paul Virilio, begins with the dedication, “To the Memory of an Era (1974-2002).” American Marxism fell to its nadir in these days, retreating to the academy and drawing most of its theoretical inspiration from so-called “Continental” (as in non-anglophone western European) philosophy via a handful of university publishers. And then there was Zizek, the man to whom we should attribute TINECUC, even if he never said it.

The Slovenian theorist Slavoj Zizek became an unlikely U.S. pop culture figure in the first decade of the 21st century; about as close to a celebrity as any far-left thinker could come, especially after his starring turns in the American documentaries Zizek! (2005) and The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema (2006). A bearded communist slob who leans into his accent, Zizek combines unapologetic Marxism with psychoanalysis and applies it to Hollywood movies as well as politics and the news of the day. His digressive, comedic style is unusual and alluring, like if Jerry Seinfeld were released from years locked alone in a cage full of books and VHS tapes and immediately thrust onstage; he has felt compelled to deny rumors of cocaine abuse. Zizek’s counterintuitive lines charmed a small but, considering the anti-intellectualism of the times, impressive slice of the country, and his prodigious output of books kept the left-wing publisher Verso afloat during this low tide.

Zizek’s daring endorsement of the revolutionary terror of Stalin and Mao was captured most distinctly in his 2008 book, In Defense of Lost Causes, with its guillotine cover — the daring being the real point. Though Zizek had hardly been a hardliner in the state socialist days, he now wielded the previous century’s red flag like a sign spinner outside an auto dealership. In the 21st century, he insisted, we can only defend true liberal values by unconditionally rejecting the exploiters who wear them as a mask. If capitalism offers us human rights-branded coffee, Zizek argued, we must reject not just the brand, but the idea of human rights. These lines appealed not least to high-school debaters, who used Zizek’s arguments to break their opponents’ conventional binaries. And though he was for a moment the most famous intellectual who strove to keep the communist tradition alive, Zizek wasn’t alone. Lost Causes was dedicated to the French philosopher Alain Badiou, whose book Ethics — another Verso title — was a popular read among American Marxists in this retrenched period. Ethics called for “fidelity” to the revolutionary socialist “events” of the past century, even as it seemed likely that they had no future.

As philosophers, Zizek and Badiou assessed Marxism’s fortunes at an ideological level. Analyzing the specific details of capitalism’s victory lap — who faced increased exploitation, where and how — went out of fashion in favor of psychological accounts of the mindset of the age. And like many other consumers, the theorists got distracted by advertising. A new “cultural capitalism,” as Zizek described it, presented ethical consumerism as a replacement good for left-wing politics, and for him that made it the worst kind of consumerism. As if to emphasize the point, Zizek wrote “anti-consumerist,” Benetton-style advertising copy for a 2003 catalog of the preppy mall clothing retailer Abercrombie and Fitch, claiming it was more ethical than working at a university. By 2009, when he published First as Tragedy, Then as Farce, he was so accustomed to making “better is worse” claims that he could say something like, “The worst slave owners were those who were kind to their slaves and so prevented the core of the system being realised by those who suffered from it, and understood by those who contemplated it.” This provocatively stupid line wasn’t really about chattel slavery, a historical phenomenon of which Zizek seems to be ignorant except as an instance of Hegel’s master-slave story; he was talking about Starbucks.

As Starbucks overcame the independent coffee shops, the chain wore its fair-trade ethic as a costume, and it was this camouflage more than the fallout from the ICA collapse that made the company outstandingly offensive to Zizek. Rather than attack the legitimacy of Starbucks’s ethos, he paraphrases it: “the price is higher than elsewhere since what you are really buying is the ‘coffee ethic’ which includes care for the environment, social responsibility towards the producers, plus a place where you yourself can participate in communal life (from the very beginning, Starbucks presented its coffee shops as an ersatz community).” It’s not clear to what degree Zizek is repeating these as claims or statements of fact, or if the distinction is even relevant to him; what matters most is to see the sales pitch as a sales pitch. Readers who truly understand Zizek and shape their ethics accordingly don’t avoid Starbucks. Rather, they order their coffee with the knowledge that it doesn’t matter where they shop and what kind of coffee they get, because their consumer choices are irrelevant. They might in fact start going to Starbucks to demonstrate awareness of the ideological nature of the very idea of “ethical coffee,” ending the kind of residual grudge against corporate java some still held from the ’90s. After all, there is no ethical consumption under capitalism.

When I began writing this essay, I started looking for the origins of TINECUC. That turned out to be more difficult than I first imagined, and the search dead-ended at the howling vortex of Tumblr. The best I could come up with was a November 2013 meme of Clippy, the Microsoft Word virtual assistant, featuring the text: “IT LOOKS LIKE//THERE IS NO ETHICAL CONSUMERISM UNDER LATE CAPITALISM.” And it is certainly possible that this post is indeed the original use of TINECUC and its variants. But I believe the proximate source of the idea behind the meme is Zizek, specifically a YouTube video in which he appears.

The British Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce (known as the RSA) launched a YouTube channel in 2009 with a video of an RSA-hosted lecture by the pop philosopher Alain de Botton (4,900 views to date). In March of 2010, the RSA uploaded a lecture from Zizek about his new book, First as Tragedy (119,000 views to date), including the bit about Starbucks. But it wasn’t until the RSA animated a ten-minute section of the talk — specifically focused on ethical consumerism — that the lecture went viral, racking up over 1.8 million views as of this fall. Though it’s unclear when those views were accumulated, it was certainly one of the most popular pieces of anglophone Marxist media in the pre-Occupy 21st century.

One of Zizek’s skills is making his written texts sound like rants when he reads them aloud, and the Starbucks section of his talk comes right out of the book — this critique of “capitalism with a human face” is likely his best-known work. “The proper aim,” he says, for the left, “is to try and reconstruct society on such a basis that poverty will be impossible, and the altruistic virtues [of ethical consumption] have really prevented the carrying out of this aim.… It is immoral to use private property in order to alleviate the horrible evils that result from the institution of private property.” (It’s worth noting that Zizek is mostly talking about charity and ethical consumerism here but that he applies the same logic to social-democratic reforms — that part of his critique has fallen out of common understanding.) Zizek concludes that anti-capitalist misanthropy is at core a more prosocial personal disposition than ethical consumerism. Without a national-scale left-wing project, it was easy for some Americans to think those were the only options, that there wasn’t a third choice.

In the decade-plus since Zizek’s video, the situation has changed, and the third choice is clearer. Following a series of national uprisings over the past decade, as well as two strong primary runs from Bernie Sanders, blaming the capitalist system is now a social pastime so prevalent it threatens to turn cliche. A new generation of self-described socialists has even sent a couple members to Congress. Verso no longer depends on Zizek and, in fact, hasn’t published any of his fifteen books since 2014’s Absolute Recoil: Towards a New Foundation of Dialectical Materialism. When the author of, among other provocations, Violence was asked about the newly popular phenomenon of Nazi-punching, he surprised interviewers by saying the really violent thing would be to refuse recognition to fascists, to ignore them. His claim that Trump could well be a better candidate for the working class than Clinton marked a hard end to the usefulness of his contrarian shtick.

And yet, the wisdom of TINECUC has become increasingly conventional. As anti-capitalism moved from the fringes to the mainstream, one of the few immunities the newer left inherited was to ethical consumerism. “The individualism of ‘ethical’ consumption,” wrote the editors of the short-lived but influential pre-Occupy journal Turbulence in 2008, “leads to an implicit antagonism with those who make the ‘wrong’ choices, and/or to ‘militant lobbying’ of governments and other authorities to impose the ‘right’ choices on people.” A new revolutionary movement couldn’t waste time converting everyone away from Starbucks, nor should it provide ammo to austerity regimes that seek to control workers’ consumption as part of an attack on the class. Unlike decades of suppressed Cold War history, TINECUC was also an easy line for newcomers to learn, not that far away from mainstream cynicism. And TINECUC became a way to signal to the unconverted that leftists aren’t a cult of weirdos who will force you to learn a litany of inscrutable restrictions — something like the way a Unitarian minister might casually reference the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue.

Now, over a third of Americans consistently report a negative opinion of capitalism. In the millennial and emerging post-millennial cohorts where anti-capitalist opinions are normal, TINECUC has become a standardized line of argumentation whenever there’s a political disagreement related to consumption. It has acquired mainstream meme status, popping up all over TikTok. Now, in 2022, it’s impossible to wade into any of the many college newspaper debates about the fast-fashion brand Shein, for example, without hearing TINECUC invoked — not incorrectly — to mean its inverse: there is also no particularly unethical consumption under capitalism. Here the phrase is exculpatory rather than an indictment. And there’s a certain truth there, especially in an era in which consumption can no longer support the world socialist project in a direct way, as the Sandinista coffee did. But it’s suspect that the Marxist line Americans have been quickest to adopt is the one that excuses them to buy stuff and, by extension, be assholes.

Zizek’s mistake was to accept the corporate purveyors of ethical consumption at their word: By making Starbucks into the poster-child for the concept of fair trade, as they wanted to be — rather than post-ICA “free” trade — he makes his job too easy. Starbucks marketing implied a humane supply chain and they offered some fair trade certified bags of coffee, which allowed them to benefit from the visual presence of the certification in front of the counter while continuing to brew uncertified low-cost beans behind it. Starting in 2004, Starbucks started labeling its coffee under its own “CAFE” standards, which unlike the Fair Trade program are not modeled on the ICA’s guaranteed minimum price system. In February 2022, Starbucks announced it was pulling cooperation with global fair trade organizations to pursue CAFE standards exclusively.

Because Starbucks doesn’t actually do any of the things implicit in its branding, Zizek obliterates the stakes of the issues at the heart of the anti-consumerist critique of the corporate coffee industry. He doesn’t have to talk about the concrete history of the ICA or the Central American coffee struggles or even the importance of independent coffee shops (copy shops, skate shops, music venues, bookstores, cafes, etc.) to left-wing movement ecology. He takes ethical consumption on its own terms. Perhaps that made sense, given how few of his readers had much of a movement to join. But this is a mistake we can no longer afford.

Assume TINECUC. No purchases can fix a system that sells exploitation, and no purchases can make any one of us a good or bad person (whatever that means) when everything is so corrupt and interdependent. Today’s moral philosophers are lining up to debate our overwhelming personal obligations to imaginary future digital consciousnesses, which makes individual ethics and clean-hands morality dizzyingly useless ways to move through the world anyway. Individual ethics, however, is not the only way to evaluate the virtues of a choice. One good reason not to go to Starbucks is that the coffee tastes bad and if that’s all we drink we’ll come to forget that it doesn’t have to taste like that.

Consumption — ethical or not — is a one-sided category that’s mostly unfit for Marxist use because it isolates one moment in our social circuits, mystifying the connection between that moment and all the others: production, reproduction, extraction, waste. A Marxist analysis of the local Starbucks would see it first of all as a site of labor struggle between workers and owners, a view that’s more readily available now thanks to the efforts of Starbucks Workers United. We would also want to understand the chain’s position as a winner in a consolidating, globalizing market, and the particulars of how the firm has raised the level of exploitation in coffee-producing areas and its effects on migration. “Capitalism is always bad” may have been good enough to keep the fire alive, but with anti-capitalism blazing away, it’s not good enough now.

If we are engaged in a collective liberation project, then we can end the debates about the individual ethics of consumption and instead begin to develop a strategic, shared analysis of our movement’s needs. We should eschew super-exploitative gig platforms not because they’re morally dirtying but because a bunch of people who are psychically dependent on underpaid delivery workers for their basic needs are not going to overthrow capitalism. (Only a philosopher could believe the words on the package in which we’ve been sold cheap abundance are a bigger obstacle to revolutionary anti-capitalist consciousness than the cheap abundance itself!) We should avoid ultra-processed foods not because they don’t have the right certification labels — sometimes they do anyway — but because they make us sick and our health is important. If we approach our needs as a strategic, collective concern, it’s not an objection to these “shoulds” to say, for instance, “Life under capitalism is so brutal that workers depend on consumer indulgences to get through the month,” or “Disabled workers have been forced to rely on capitalist products and services to survive in a hostile society.” On the contrary, that’s simply to reiterate the immediate need for different ways to live.

We shouldn’t take that Hawaiian vacation, not because it’s unethical by whatever philosophical standard, but because it undermines the struggle of Kānaka Maoli organizers who are in a specific and urgent fight for the future of their nation, which is part of the world struggle in which the “we” to whom this essay is addressed consider ourselves participants. We need to go see left-wing music and movies (and subscribe to small magazines, of course) not because otherwise we’re lamestream sellouts but because cultural products can ennoble or stultify and the ruling class would rather have us stultified. And we need left-wing cafes not so we can show off our unnecessarily expensive Veblen goods but because we need places where workers can read behind the counter and sneak free stuff to their comrades, where we can meet on purpose or by accident, where we can find help in an emergency.

Malcolm Harris is the author of Kids These Days: Human Capital and the Making of Millennials and the forthcoming Palo Alto. He lives in Washington, D.C.