Image by John Kazior. Source image credit: user:424ccdrums / Wikimedia, Maersk Line / Wikimedia, and GretXP / Sketchfab.

Image by John Kazior. Source image credit: user:424ccdrums / Wikimedia, Maersk Line / Wikimedia, and GretXP / Sketchfab.

The H.R. software provider syd™ may ask you to submit your spit. But even if you decline to supply a saliva sample, it will still request your dietary and financial information. All this, plus your environmental data (like your home address and the temperature outside), is used to create a digital copy of you, which syd™ delivers to your boss, who can then use it to track your “Life Quality,” as measured by indices like “brain power” and “purpose.” Because the syd™ app is integrated with Apple Health and Google Fit, those categories can be updated in real time. “The higher your people’s Life Quality Index™ is, the more you save,” syd™ promises. And workers benefit, too. Participating staffers receive “Life Quality” recommendations, like “read an article about finance,” “eat some grapes,” and “be grateful.” The software provider is tight-lipped about its client list, but business appears to be booming. In 2024, syd™ announced plans to create a “population analytics dashboard” for the government of the United Arab Emirates.

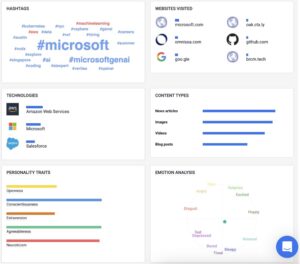

syd™ isn’t the only company that sells bosses copies of their staff. Delve, an A.I. startup that launched in 2023 and counts the University of Florida and Lexus among its clients, markets digital Rolodexes of “employee personas.” With Delve, managers can peruse their underlings’ digital profiles, each of which features a headshot alongside a highlighted quote and a collection of “persona cards,” including a word cloud filled with hashtags, an “emotional analysis,” and a bar graph of personality traits. On its website, Delve provides a sample “persona card” for a Microsoft employee named Brady Hamm. Beneath a headshot of a lightly bearded white man, a caption tells us that Brady is 34, “urban,” and “millennial,” and a handy map shows us that he’s based in San Francisco. Brady’s primary personality traits are conscientiousness, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Brady’s mood falls in the “sleepy” and “relaxed” quadrant of Delve’s emotion radar chart. He is a fan of “#summer,” though the biggest hashtag in his word cloud is “#microsoft.”

Brady leaves work in the evenings, but his persona stays online all night in case his manager wants to talk to a Brady chatbot, which has been fed the software engineer’s “psychographic” information and “demographic attributes” such as income, education, location, and “family status.”

The personas created by platforms like syd™ and Delve are called digital twins, a term that originates in the fields of industrial design and engineering. A digital twin is a continuously updated virtual version of a physical space, object, or asset, like a digital assembly plant or a digital jet. In 2022, the trade magazine Mining Weekly reported on “the first 100% digital mine in Peru,” a digital twin of the Quellaveco copper mine, which is operated by the British multinational Anglo American. Each piece of equipment at the mine is outfitted with sensors that continuously beam information from the Andes to the company’s London headquarters. Anglo American boasted that the twin’s ability to perform tests on the mine’s grinding, electrical, and flotation systems has made them safer and more efficient. In 2023, BMW launched a “Virtual Factory,” which replicates every drill and conveyer belt exactly as it appears at the company’s new two billion dollar plant in Hungary. The digital twin can “automatically check for possible collisions” on the production line without putting real-life cars in harm’s way, according to the carmaker, which is expanding the project to include models of more than thirty production sites worldwide.

Although twin technology rarely receives the fawning media coverage lavished on A.I. and Web3, it is increasingly seen as cutting edge within the tech and business worlds. The global market for digital twins was valued at $17.7 billion in 2024, according to Fortune Business Insights, and McKinsey expects that number to reach $73.5 billion by 2027. The World Economic Forum has said, in a report, that digital twins will bring about “the fourth industrial revolution” — a concept echoed in a 2019 TED talk titled “Sparking the 4th Industrial Revolution by Thinking Spatial.” The first industrial revolution, in the middle of the eighteenth century, gave capitalists steam power and mechanization. The second, at the turn of the twentieth, ushered in electricity and the assembly line, and the third, some seventy years after that, computers. The fourth, apparently, will let middle management play The Sims.

The phrase “digital twin” was popularized by the research scientist and business executive Michael Grieves in a 2014 paper. He began writing about the concept in 2002, but internet speeds and computing power needed more than a decade to catch up. So did the parts market: sensors dropped in price by more than half between 2004 and 2014. Then, during tech’s fabled post-financial-crisis “free money era,” the Fed held interest rates low and a tsunami of cheap parts flooded product markets. The conditions were right for twin technology to take off — in some cases, literally. In the years following the publication of Grieves’s 2014 paper, NASA and the U.S. Air Force began to engineer digital twins of spacecrafts and fighter jets.

But Grieves had in mind more earthly pursuits: he thought the technology could help the global asset-owning class enact a fantasy of total workplace control. In his 2014 paper, he called for “factory replication,” which would bring about a kind of supercharged workplace surveillance. Managers would no longer need to have “their office overlooking the factory so that they could get a feel for what was happening on the factory floor,” Grieves wrote. “With the digital twin, not only the factory manager, but everyone associated with factory production could have that same virtual window to not only a single factory, but to all the factories across the globe.”

By 2021, in the aftermath of the Covid labor market shock, business analysts and academics were dreaming of twinning people, too. That year, Wei Shengli published a report in Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine Update that summarized Grieves’s ideas and asked whether it was possible to replicate individual humans. Shengli listed the salient differences between humans and machines (“human beings have mental activities,” for instance, and respond to changes in “diet” and “bacteria”) and concluded that, with the right “biosensors,” and with “smart devices” that were both “high performance and cheap,” building “human digital twins” was possible, in theory — but it was likely a long way off.

That didn’t stop others from thinking about replicating white-collar workers. That same year, ServiceNow, a major I.T. software provider, published “The case for creating an employee ‘digital twin.’” An employee digital twin could do things like suggest “that its human counterpart might improve their performance if they took training classes tailor-made to their strengths and weaknesses” or recommend that a manager “reduce an employee’s workload because the digital twin appears to be heading toward burnout.” As a blog post from the H.R. technology company Unleash pointed out, “implementing digital twin technology can streamline operations, reveal new insights, and evolve recruiting and workforce development when applied to H.R.” It went on to quote an executive at an H.R. software company who mused, helpfully, that “people are also physical assets.”

Industrial twins, on the other hand, prioritize actual physical assets. A typical digital factory has the look of an expensive P.C. game, if the goal of the game were to be a good steward of your employer’s capital investments. Using a twin, engineers can model, monitor, and manipulate pumps, levers, pistons, and belts with computerized precision. The workers who actually use these tools are typically an afterthought. Often, twin software uses visual clues to show that, although the things pictured have real-world referents, the people do not. Consider a still from a promotional video for BMW’s virtual plant: a gray man, who looks like he was 3D-printed (and is, in fact, one of the carmaker’s many “artificial intelligence-powered digital humans”) pats a midsize SUV lovingly rendered in BMW’s trademark “Estoril Blue.”

Other companies make more of an effort at verisimilitude. In a video released by the digital twin company Sentient, a square-jawed man resembling Woody Harrelson in a hard hat wanders around a virtual mine, speaking into a walkie-talkie and pressing buttons.

Although these workers look generic, buyers and boosters insist that industrial digital twins make the real workers they approximate safer. At BMW, there were “situations where the visualization of robot arm movements in the virtual world prevented the potential destruction of a catwalk in real life,” the company’s representative told reporters in 2023, referring to the high-up, delicate walkways workers use to get aerial views of assembly lines. Supposedly, digital twins risk their necks so that workers don’t have to.

In actuality, the ways employers deploy digital twins to shore up profits are often at odds with workers’ health and safety. In 2020, for example, after the English pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline purchased a digital twin of its plant in Hertfordshire, line speeds at the plant increased by 21 percent, forcing workers to move more quickly. Fast assembly lines are dangerous assembly lines. In the U.S., a Minnesota district court recently ruled that speeding up pork and poultry lines puts workers at a higher risk of extremity pain and musculoskeletal disease. In 2019, when the USDA eliminated line speed limits at pork processing plants, the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union demanded “additional staffing, improved reporting of workplace injuries, expanded access to early and adequate medical treatment, and job modifications that minimize ergonomic stressors.” Add in digital twins, and the benefit of any workplace accidents avoided is far outweighed by the costs of greater efficiency: the rhetoric of safety gives companies cover to reject labor advocates’ demands for better working conditions while tightening up surveillance and actually damaging workers’ health.

And so far, at least, even the benefits to business owners are questionable. Empirical studies show that gains from digital twins are marginal, at best. Typically, twinning a factory costs between six hundred thousand and eight hundred thousand dollars, and according to the consultant Paul Leghorn, it takes buyers about nine years to recoup that kind of investment. In 2018, researchers with the University of Sheffield’s Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre estimated that digital twins save companies one to three percent on capital equipment outlays, cut unplanned downtime by fifty percent, and cut maintenance costs by forty percent. But, in 2019, when Unilever implemented digital twin technology to optimize the manufacturing of soap and ice cream, productivity gains were modest — just one to three percent.

In the corporate world, one to three percent gains can be significant, but they’re hardly a fourth industrial revolution. Indeed, the rise of digital twins is a symbol of the shrinking imagination of the industrial capitalist class. In 2022, Planon, a workplace management software provider, published a piece of fiction-cum-ad copy on LinkedIn that recounts a day in the life of Hilde, an office worker from the year 2062. Workplace management software has unlocked hitherto unimagined levels of efficiency. Hilde’s company has an office on Mars. She chats with her off-planet colleagues via holograph. “By 2025,” she explains to a younger coworker, “we were using digital twins for all sorts of things, not only to predict equipment behavior and maintenance needs, but also to model the behavior of people.” This alerted management, she says, to a grave inefficiency: staff members were spending too much time waiting for elevators. “It just seemed too long,” she explains. “So we used our digital twins to model what a more efficient elevator control system might be able to do.” Hail, the march of progress: faster elevators.

Back in 2016, Bill Ruh, the former CEO of GE Digital, told a Wall Street Journal reporter that one day “we will have a digital twin at birth, and it will take data off of the sensors everybody is running.” These twins, he added, will “predict things for us about disease and cancer.” Maybe so. But in the meantime, most of us will spawn a series of simulated selves, cryogenically frozen and left to languish in the digital archives of our past employers every time we go back on the job market. Our twins will make guesses about us based on our zip codes, incomes, and saliva samples. The benefits of digital twins, such as they are, will accrue to bosses: simulated employees dissimulate the real stakes of people management, and industrial digital twins make workers anonymous, hiding the pain that process optimization inflicts on the workforce.

Yet the ownership class has so far failed to realize the infinite value prophesied by Grieves. This may not come as much of a surprise. The Marxist historian Robert Brenner has called the period starting in 1973 and continuing into the 2020s — a half-century of reduced economic dynamism and accelerated deindustrialization — the “long downturn.” In Brenner’s account, as German and Japanese manufacturers caught up to their American counterparts, global manufacturing capacity grew too quickly. Worldwide industry could suddenly produce more consumer goods than people could possibly buy. This imbalance caused producers to compete on price, rather than quality. At the same time, manufacturing productivity began to stagnate. Economists still debate the reasons, but few dispute the reality. Early hopes that the personal computer and internet revolutions would reignite industrial productivity growth have now mostly dissipated.

Some economists, like Robert Gordon and Tyler Cowen, say that we have simply already plucked all the low-hanging productivity-enhancing fruit — mechanization, standardization, electrification, computerization — and that we may never again see the big leaps of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Comparing this century’s productivity growth rates with those of the postwar era, the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that slowing productivity growth has cost the American business sector more than $10.9 trillion since 2005. syd™’s ad copy (admittedly, a less reputable source) sets the cost of low productivity in the U.S. at $1.5 trillion each year. Companies looking to compete on price with global rivals turn to digital twins — despite the technology’s meager benefits — because they have pinned their hopes on petty cost-cutting measures. Insiders expect companies in the slowest-growing sectors of the world economy to spend the biggest sums on simulations in the next few years. Digital twins are palliatives — they treat the symptoms, not the causes, of flagging productivity growth.

In common sense terms, then, digital twins don’t create a whole lot of anything. They defray maintenance costs and bump up owners’ returns on investments — and not even by all that much. “Even if the virtual factory doesn’t revolutionize the design process of the car,” BMW’s “Digital Solutions Architect” Felix Theurer explained, “we can still say that it helps to improve the return on capital employed when setting up the whole production system.” BMW isn’t reinventing the wheel, in other words; it’s capturing an image of the wheel, and the axle that the wheel spins on, and the chassis that’s mounted on the axle, and the doors that swing open from the chassis, in lush detail, to save one to three percent on the machines that make cars.

The main reason, then, that digital twins have attracted so much investment may be that there isn’t much else that looks promising. It appears that as real productivity growth increases remain out of reach, the last resort for capital is the automation of worker oversight — or what the writer Jason E. Smith has punningly called “managing decline.” Digital twins assist in supervising (not supercharging, revolutionizing, or reimagining) production. For all the anxiety today about robot-induced unemployment, the main application of new tech in the workplace is to discipline employees, not to replace them. Simulations aren’t coming to steal your job. They’re coming to make your job worse.

For now, they’re fun toys for the rich. LinkedIn cofounder Reid Hoffman — who once told a class of Stanford students that an interest in work-life balance was a sign of not being “committed to winning” — recently trained a digital twin on his own books, articles, and media appearances. The twin, Hoffman said, could inspire “new ways of thinking and connecting ideas.” In a 2024 Hoffman-on-Hoffman video interview stunt, the billionaire asked his digital twin how his own book, Blitzscaling, might be summed up by Jerry Seinfeld. “Blitzscaling, you know, it’s when a company decides to floor it on the highway of business,” the twin answered weirdly. This year, the twin gave a keynote talk at the Silicon Valley Video Summit. On screen for about thirty minutes, it delivered prepared remarks, rhymed (“three hundred languages translated with finesse / from Mandarin to Klingon / yes, I impress”), and answered live questions from the audience.

When not speaking, the twin twitched and flapped, as if to mimic human hand gestures. “What’s your favorite movie?” an audience member stepped on stage to ask. “I don’t have personal experiences or tastes,” the twin began, before explaining that “for Reid, a movie like The Matrix might be particularly intriguing.” At this point, Hoffman’s real-life employee, who moderated the discussion, stepped in: “I never cut off the real Reid, but this Reid I do cut off a lot,” he said. “Wait, Reid-A.I., are you in the Matrix right now?” asked an “A.I. specialist” from the Office of Reid Hoffman. The twin spun its hands for a few seconds then responded, “Well, you could say I’m in a kind of digital matrix of sorts, not in the sci-fi sense where I’m trapped in a simulated reality,” before uttering nonsensical syllables “bat!” and “dissing,” and fully glitching out, like a food delivery robot whizzing into oncoming traffic.

Max Hancock is a PhD student at the University of Chicago. He studies U.S. history and the history of capitalism.