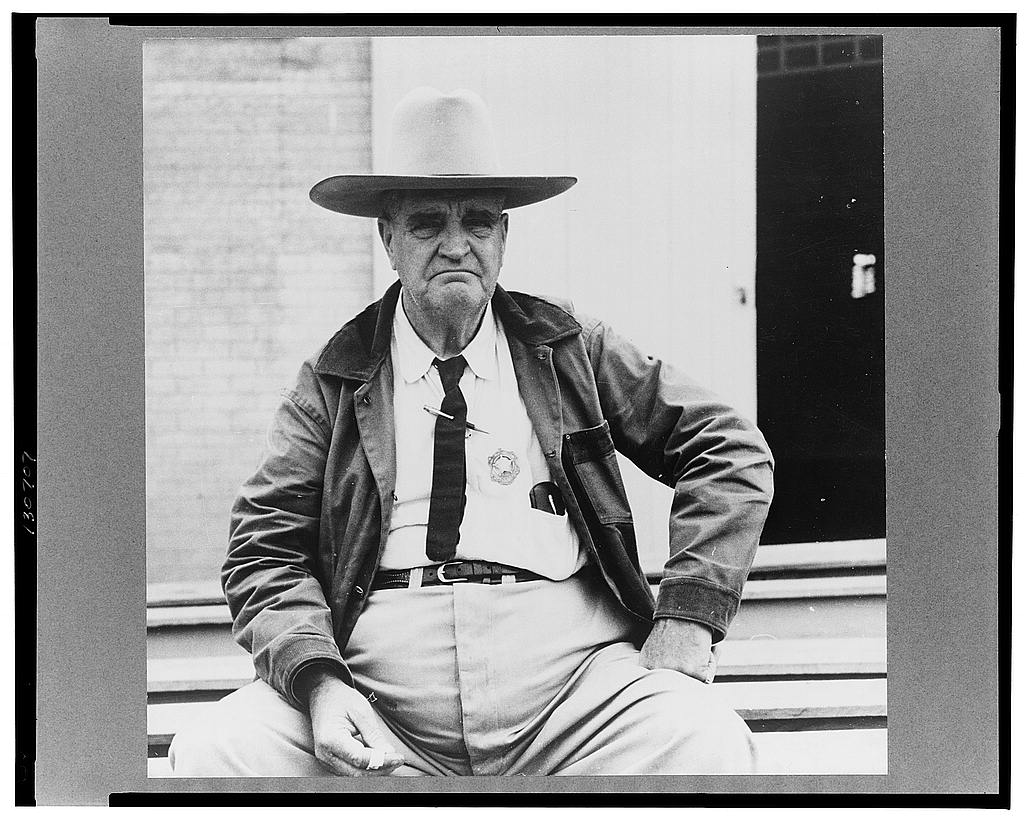

Deputy sheriff at county fair, Gonzales, Texas. Photograph by Russell Lee, 1939.

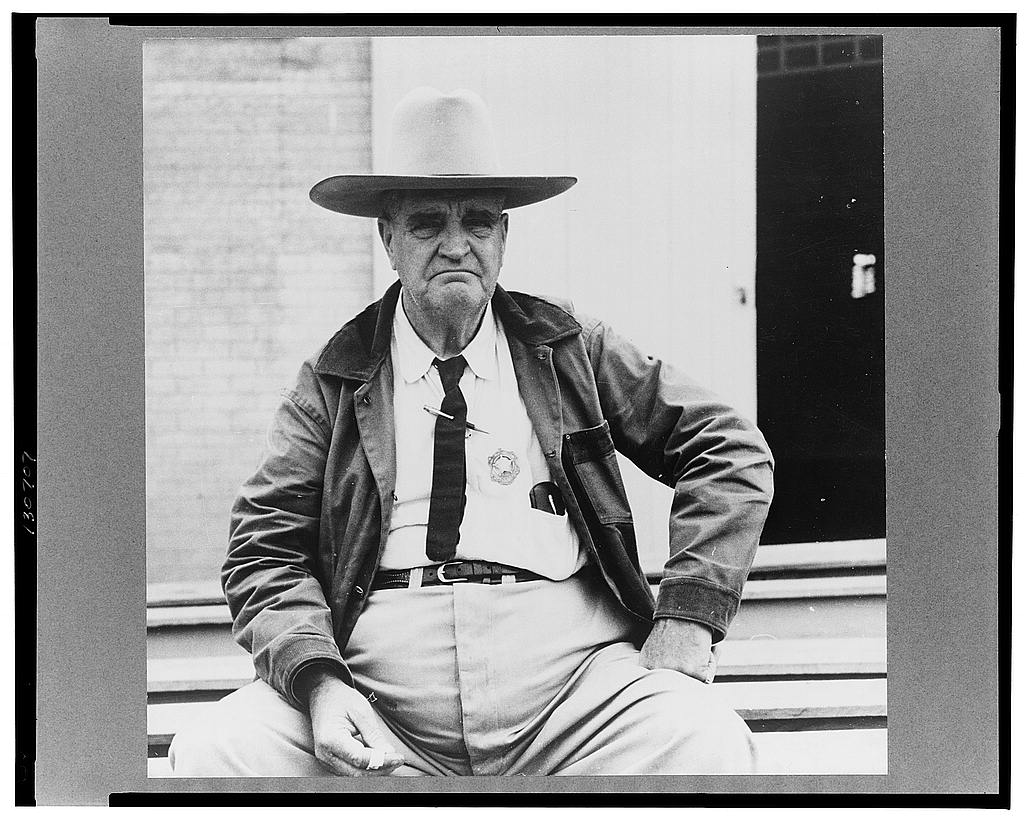

Deputy sheriff at county fair, Gonzales, Texas. Photograph by Russell Lee, 1939.

Big Harris Rood had spent his life growing cotton on a plantation near Lumpkin, Georgia. He had been free from bondage for less than a year when three white robbers arrived outside his cabin late one night in early 1866. After a brief argument, Rood killed the leader, driving an ax into his skull. The next day, the dead man’s father swore out a warrant and traveled to the Rood Plantation, part of a group of more than seventy white men led by the county sheriff. Both a white supremacist mob and an arm of law enforcement, they were coming to arrest Rood — and sow terror among the neighbors who had helped fight off the robbers.

As the sheriff’s posse approached the plantation, some of the men began shooting at freedwomen and children in the cotton fields. Rood’s neighbors returned fire and killed a member of the mob. The ensuing dustup ended with the arrests of sixteen freedpeople, including Big Harris. One man was shot and killed while in handcuffs by Judge Walton, the justice of the peace who had signed the original warrant. Neither he nor any other member of the posse would face consequences.

Rood, in contrast, was convicted of murder before an openly white supremacist judge and sentenced to hang. But the Freedmen’s Bureau, set up by Congress to assist freed slaves, lobbied the governor and managed to delay his execution. As he sat in a jail cell for two years, violence and injustice across the South led Republican politicians to put Georgia and other Southern states under military rule and extend suffrage to Black men. In the spring of 1868, Rufus Bullock was elected governor of Georgia with the overwhelming support of the state’s Black voters and commuted Big Harris’s sentence. Rood’s life was saved by Radical Reconstruction.

As W.E.B. Du Bois wrote, during Reconstruction, Black Americans “stood a brief moment in the sun,” and multiracial democracy appeared possible. A society that had organized itself around the profits of enslaved Black labor for more than two centuries was — often literally — in rubble, and the former ruling class was unmoored. In the spring of 1865, the twenty-five-year-old daughter of a prominent Georgia family wrote in her diary: “The props that held society up are broken.… The suspense and anxiety in which we live are terrible.” For the formerly enslaved, on the other hand, 1865 was a year of jubilee: a time to imbue freedom with meaning, to start new lives independent of their former masters, to locate friends and family members who had been sold away during slavery.

The South in 1865 was not a blank slate, but an open field for a new battle. This fresh struggle would pit those who embraced Black citizenship and wished to consolidate the gains of emancipation against those who aimed to use the law and the power of the state to continue profiting from Black labor. In the mid-1870s, the federal government retreated from its support of the freedpeople, and white planters violently retook control of the region. The political wing of this counterrevolution was the Democratic Party, but its paramilitary wing was divided in two: in rural areas, it wore Klan hoods; in cities, it donned police uniforms.

This bifurcation of state power across urban police forces and rural sheriffs is one that persists today. Urban police, especially those in our biggest cities, receive the bulk of media attention, but for millions of rural Americans the primary agent of law enforcement is the county sheriff, just as it was for Big Harris Rood in 1866 — a distinction that tends to get lost in contemporary discourse that treats all “cops” as identical. It understandably matters little to a protestor getting beaten whether the person doing the beating is a sheriff’s deputy or a city police officer. But as we begin the process of rethinking American law enforcement as a whole, these structural differences can help us determine what kind of change is possible.

The past few years have seen a growing awareness that American law enforcement — across departments and agencies — is not politically neutral. On January 6th, the nation watched as Capitol Police posed for selfies with white supremacist insurrectionists. Many off-duty officers attended, and police leaders across the country expressed support. Millions more Americans now see the police not as enforcing the law, but rather upholding racial hierarchy and advancing conservative “law and order” politics. Thanks to last summer’s massive Black Lives Matter protests, the range of potential solutions to police abuse has expanded dramatically, and the possibility of defunding or abolishing the police has become a major topic of debate.

As such ideas enter the political mainstream — and as left-wing candidates win elections, often over the objections of police unions — we are confronted with the question of how to translate anti-police energy into concrete policies. This means, in part, deciding which elements of our country’s law enforcement apparatus are necessary, what histories can be unwritten, and what powers must be curtailed or eliminated. To make these decisions, we must not simply attack the right-wing “thin blue line” narrative; we must confront our own myths as well.

Though Reconstruction has recently gained new attention in mainstream media, it is still sculpted to fit a narrative in which slavery is inevitably and immediately followed by Jim Crow. In The New Jim Crow — the twenty-first century’s most influential book on criminal justice so far — Michelle Alexander speeds past Reconstruction in less than a page, declaring, “Sunshine gave way to darkness, and the Jim Crow system of segregation emerged.” In her telling, slave patrols were reconstituted as police forces; Black convicts were forced to build railroads and grow cotton; the Thirteenth Amendment allowed for re-enslavement through the prison system; and Black Americans were left with a largely meaningless freedom. Reconstruction, insofar as it is worth discussing at all, was doomed to fail because white supremacy is the immovable foundation of the American state. Thus, there are no lessons to draw from the accomplishments of Reconstruction and little reason to analyze how it was defeated.

This narrative persists because, on one level, it is accurate: white supremacy has always been central to the economic and political structure of the United States. Its form, however, has never been static. As Malcolm X once said, “Racism is like a Cadillac. They bring out a new model every year.” Jim Crow and, later, mass incarceration were new, innovative instantiations of white supremacy and racist injustice unlike older forms. Moreover, they were the results of conservative reactions against the Black political power won during the first and second Reconstructions, a point that Alexander makes well. But skating over the revolutionary rupture of Reconstruction betrays a fundamental pessimism that denies the possibility of political progress.

Eliding Reconstruction also makes it easy to draw a straight line from pre-Civil War slave patrols to modern policing. Though the perceived continuity between slave patrols and modern police forces holds a central rhetorical position in the fatalistic narrative of the post-Civil War era, the connections between the two are often based on a static and abstract conception of police and law enforcement. Moreover, they do not hold up against the broader history of policing or the way that state power is enacted in the United States. The incarnation of policing most familiar to us today does not trace its roots to Southern slave patrols — police forces existed both in Northern cities and in Europe well before the Civil War. London’s Metropolitan Police, for one, was created in 1829 and modeled on the force that Prime Minister Robert Peel had managed in colonial Ireland. (The British slang “bobbies” refers to Peel.)

Prior to emancipation, a few Southern cities maintained small, primitive police forces. These were distinct from rural slave patrols, which sent rotating groups of white volunteers out at night in search of enslaved people attempting to travel without permission. In addition to slave patrols, the official institutions of law enforcement in rural areas took the form of sheriffs and courts. After the Civil War, Southern states did not create rural police forces, even though the vast majority of Black Southerners lived in rural areas. Instead, they relied on the private violence of the Ku Klux Klan and lynch mobs to support sheriffs, enforce white supremacy, and keep the majority of rural Black families working as perpetually indebted sharecroppers.

Rural law enforcement, in its official capacities, remained relatively weak, allowing the Klan to step in and exercise its own violent and murderous power at will — often with the support or participation of sheriffs. This set up a very different dynamic in daily policing than the one that emerged in Southern cities and persists today. Urban police forces, meanwhile, were built up in reaction to the growth of Black political and economic power that followed emancipation. The Klan descended directly from the slave patrol; Southern police forces were a reaction to Black freedom.

Southern police forces were not reconstituted slave patrols. Rather, they were a new Cadillac: the white supremacist state adapting to the growth of a politically empowered urban Black population. After emancipation, white leaders in Southern cities began to see potential value in robust police forces. Cities that did not have their own forces created them, and those that did modernized and expanded their forces. The explicit goal was often, as the Atlanta City Council held, to manage social shifts “attributable to the changed station of the negro.” As Black men and women moved to cities in search of opportunity and an escape from rural violence in the first decades after emancipation, they encountered heavily armed white police forces that had recently been created to control urban Black labor and attack Black political power.

At times, cities deployed their police forces to carry out brazen acts of paramilitary political violence. In July 1866, Louisiana Republicans attempted to reconvene the state constitutional convention to enact universal male suffrage. One hundred Black men marched in support towards the New Orleans’s Mechanics Institute, where the convention was held. When they arrived, they were attacked by a group of over a thousand white men, including many of the city’s newly minted policemen. The new Democratic mayor had purged the ranks of the force, replacing Union supporters with Confederate veterans willing to use arms to enforce white supremacy. The police-led mob stormed the Institute, shooting the unarmed and cornered delegates; some officers pretended to offer the delegates protection, only to attack them. Union troops stationed in Louisiana did not arrive until well after at least 34 Black men were killed.

A Congressional investigation of the massacre found that police had conspired with white supremacists and Democratic politicians to attack the meeting. Angered by persistent anti-Black and anti-Republican violence throughout the South, Northern voters propelled a Republican landslide in the 1866 elections. Republicans then used their majorities in Congress to pass a series of Reconstruction Acts placing the ex-Confederate states back under military rule and requiring Southern states to guarantee Black voting rights and ratify the Fourteenth Amendment.

A decade later, as gains made under Reconstruction were systematically rolled back, urban police forces underwent a subtle shift. It is this era in which the narrative of a “neutral” police force took hold. With Democrats in charge of every level of government, police no longer needed to be directly associated with the kind of violent and explicitly partisan politics that had attracted the ire of the North. Instead, Southern police moved towards the institutionalized, systemic violence of policing that was needed to support the developing system of Jim Crow. Between the 1890s and 1960s, Southern states used both police forces and the terrorist violence of lynching to uphold the racial hierarchy inscribed in law.

Police forces in Jim Crow cities did not simply respond to reports of crime; as they trudged across their beats in the summer heat and winter rain, they used their power to proactively criminalize citizens. Policy choices made by white political leaders focused policing on Black communities, and the daily grind of arrests and beatings targeted Black residents. Today, the same policy choices in urban policing lead to the same result: disproportionate arrests and violence directed at Black citizens. State violence has never been apolitical, but during Jim Crow, its non-partisan nature helped perpetuate the idea that the police were primarily engaged in enforcing neutral laws — even as they upheld a formal system of white supremacy.

The story of Big Harris Rood contains no police, but it showcases the power, in rural counties, of elected law enforcement officials such as county sheriff and justices of the peace, especially when they were assisted by armed men. Even as the Democrats’ violent takeover of the South proceeded, some Black communities, particularly in rural areas, were able to supplement self-defense with the control of local offices, including that of sheriff — a project made possible by the decentralization of state power in the United States. Contrary to popular conceptions, and even with the radical expansion of the “national security state” since 9/11, state power in the U.S. remains nearly as decentralized as it was during Reconstruction.

Technological advances (the telephone, the car) have changed how sheriff departments operate, and today they resemble urban police forces much more than they did in Rood’s time. Nonetheless, sheriffs are usually elected and have a much broader array of responsibilities than urban police, such as managing county jails. Of the more than 3,000 sheriffs in the United States, most were elected, have minimal training, and receive little to no oversight from county and state governments. Unlike police chiefs, moreover, they cannot be fired. Sheriffs’ plenary authority frequently leads to abuse — but also presents an opportunity for change.

Sheriffs who rise to national notoriety tend to be famous for their brutality. Jim Clark, who served as sheriff of Dallas County, Alabama from 1955 to 1966, ordered the attack on the Edmund Pettus Bridge during the Selma to Montgomery march. David Clarke, sheriff of Milwaukee County, Wisconsin and featured speaker at the 2016 RNC, became notorious after a man imprisoned in his jail died of thirst. Perhaps most infamous of all is Maricopa County, Arizona sheriff Joe Arpaio, who routinely violated the Constitutional rights of his constituents and housed incarcerated men and women in tent cities in the scorching Arizona summer.

Across the country, however, sheriffs with no public profile also abuse inmates and violate the rights of their constituents. Most recently this has been made clear through the horrific spread of Covid-19 in rural jails. Mass incarceration is usually thought of as an urban issue (in part because “urban” is commonly used as a euphemism for “Black”), but in recent years, rural jail populations have been among the fastest growing in the country. By the Vera Institute’s calculation, rural counties and medium and small metro areas have 44 percent of the country’s population but 53 percent of jailed citizens.

Like urban police forces, sheriffs and their deputies have also cooperated with, or been members of, far-right groups. A Michigan sheriff named Dar Leaf defended the men who were arrested for plotting to kidnap Governor Gretchen Whitmer, arguing that they simply wanted to conduct a citizen’s arrest of the tyrannical governor. (Leaf also spoke alongside one of the plotters and the Republican State Senate Majority Leader at a “Liberate Michigan” rally.)

Even more disturbing is the rise of the self-described “constitutional sheriff.” Constitutional sheriffs explicitly embrace a far-right ideology, one that is largely shared by sovereign citizens and other anti-government militia groups and considers the federal and even state governments to be illegitimate. Constitutional sheriffs believe themselves to be the only rightful agents of law enforcement, declaring a refusal to enforce laws such as gun reforms and, more recently, COVID restrictions. Unsurprisingly, constitutional sheriffs have both praised the January 6 Capitol riot and blamed it on Antifa. Like sheriffs during Reconstruction, they place white sovereignty above democratic decisions made in the state house. Many sheriffs take the discretionary aspect of policing to the extreme, embracing the tradition of private white supremacist violence and the premise that the law is what white men say it is.

These sheriffs believe their unaccountable power is legitimate because it flows directly from the people through democratic election. That logic has historically been tied to restrictive visions of white male citizenship, but it need not be. The same unchecked power that has been so often abused by white supremacist sheriffs can be wrested from them at the ballot box and used for radically different ends. As during Reconstruction, we can take advantage of the decentralized nature of law enforcement to protect our communities from white supremacist aggression, whether from far-right groups or the state and federal governments.

So far, much of the focus of police reform and abolition efforts has focused on big city police departments, but these can be the most impervious to change. Urban police unions are often willing to make implicit and explicit threats against politicians who challenge their power. This doesn’t mean that mayors and city councils should not be pushed to change policing policies — indeed, some cities are taking drastic steps to reduce the power of their police forces — but simply that there are more direct ways to change policing and criminal justice policy.

The most prominent electoral criminal justice reform strategy has been to elect progressive district attorneys like Larry Krasner in Philadelphia or George Gascón in Los Angeles. So far, these new DAs have produced significant gains for decarceration, but the power of the office allows them to go well beyond reducing prison populations. DAs can protect elections, target wage theft, prosecute polluters, expand sanctuary city policies, and root out racial discrimination in hiring and housing. In addition, they can marshal their powers against far-right violence — whether by private actors or police — rather than anti-fascist activism.

District Attorneys are not the only local elected officials who can dramatically counteract mass incarceration. Regardless of who controls Washington, D.C., county-level officials manage elections. In much of the country, judges who preside over both criminal trials and lawsuits against the police are elected. Even many coroners, who determine the cause of death in police killings, are elected. In short, there are many levers for activists to change or eliminate policing and mass incarceration. Many local offices need to be filled, and winning those contests is much easier and cheaper than those for federal offices.

In recent decades, sheriff elections have usually been uncontested. Recently, however, these contests have gained more attention from progressive activists, due in part to the tireless work of Daniel Nichanian and Jessica Pishko. In 2020, progressives defeated conservative sheriffs who cooperated closely with ICE in Massachusetts, Georgia, South Carolina, and Ohio, but the office still remains largely absent from discussions about police reform and abolition. Sheriffs have almost unfettered power, which frequently leads to abuses, but also could give a progressive sheriff the ability to, for example, stop making arrests for drug possession. Elected sheriffs choose what crimes to prosecute, how many people to hold in jail, and whether to turn undocumented immigrants over to ICE.

Though wielding power is always fraught with compromise, short of revolution, it is the goal of politics. This does not mean simply telling the police to point their guns elsewhere or putting a progressive sheen on mass incarceration, but spurring a broader shift that uses the power of the state to combat harm, whether it is racial discrimination, tax fraud, or pollution. Even within the structures of the current American government, with its history of brutality and foundation of racism, there is room to drastically reduce the number of people who experience violence at the hands of white supremacists — whether or not those white supremacists are employed by the government.

Jonathon Booth is a PhD candidate in History at Harvard University studying race, law, and policing after slavery.