Illustration by Emma Kumer

Illustration by Emma Kumer

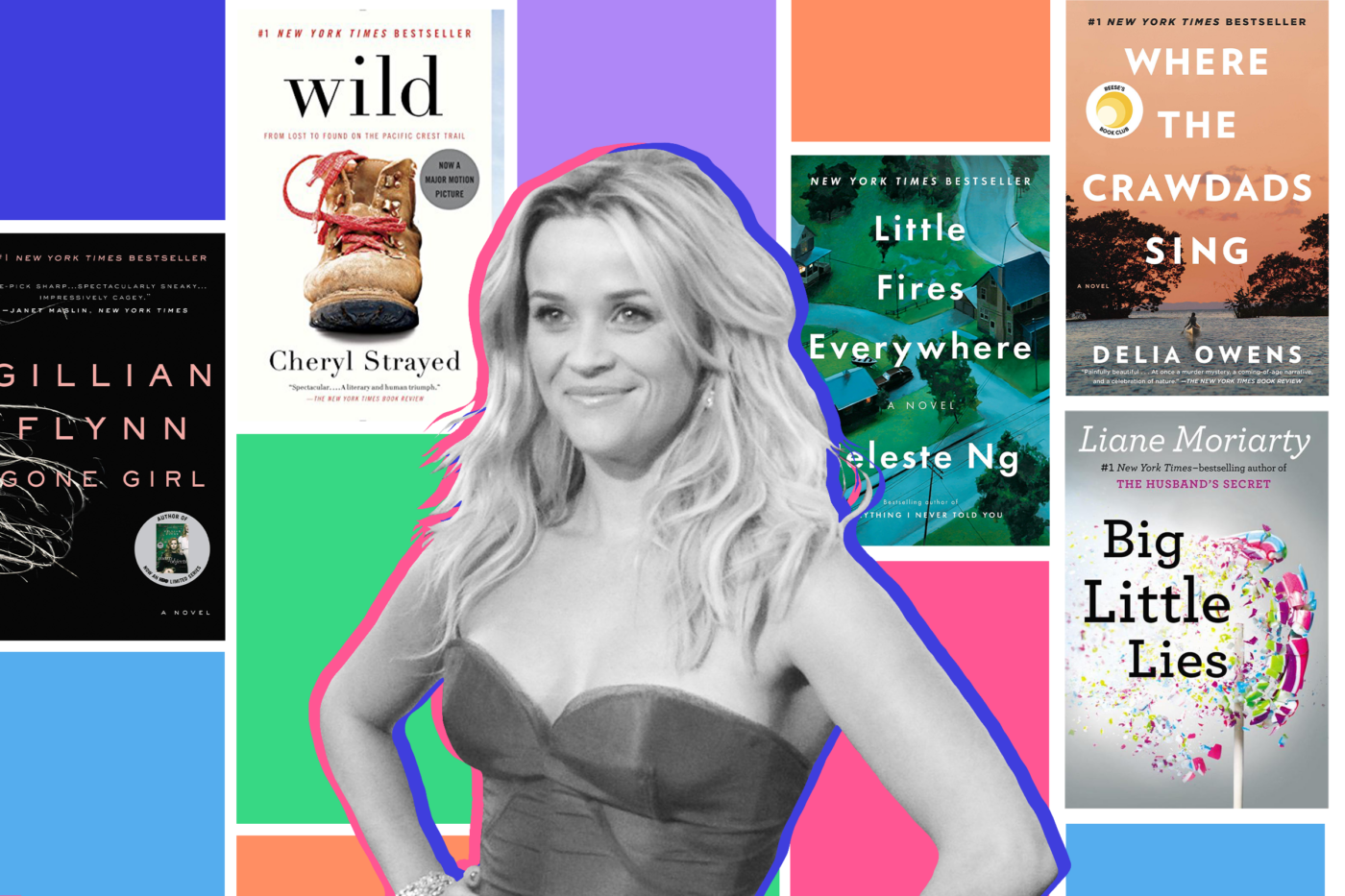

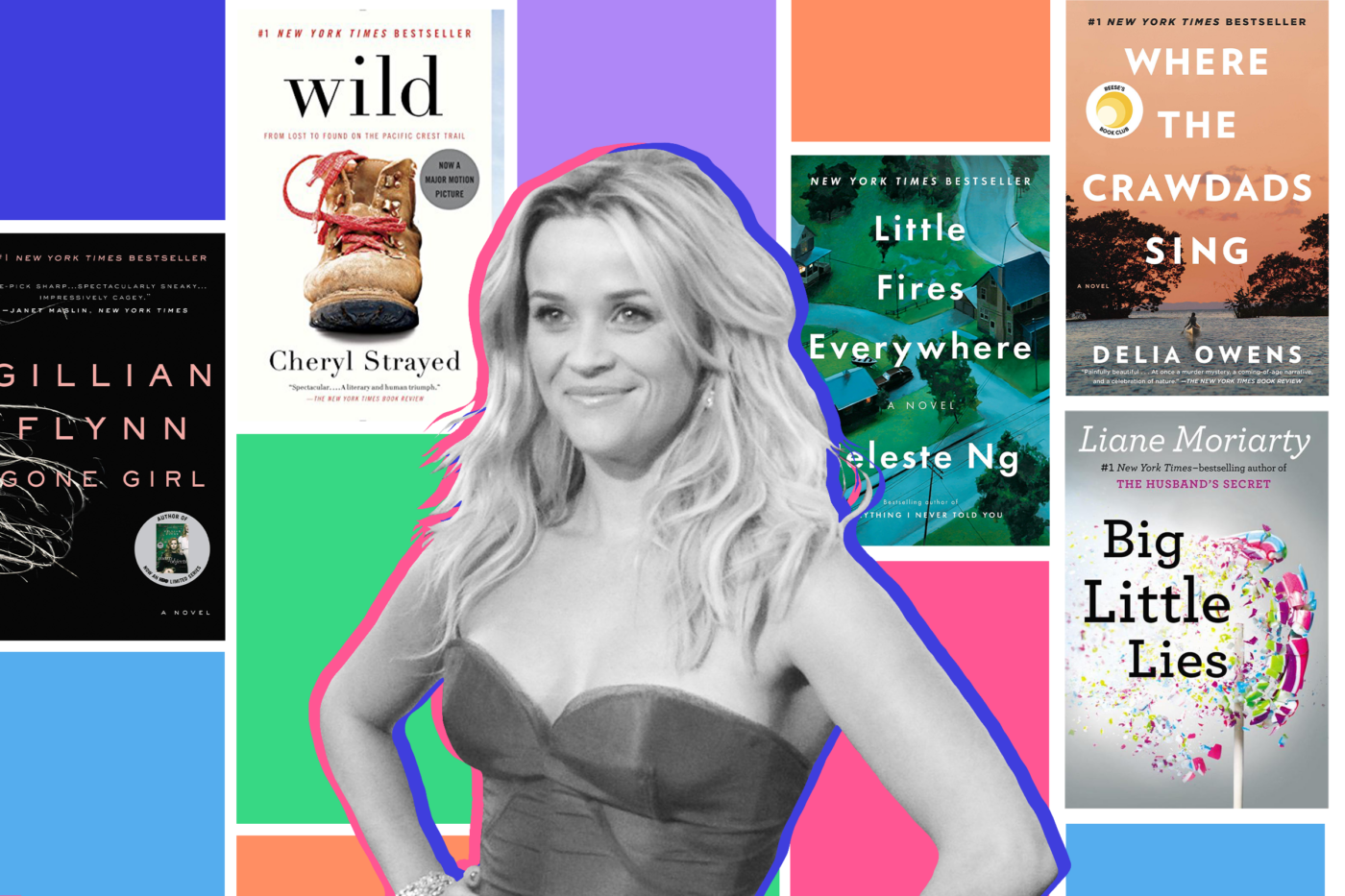

In 2012, Reese Witherspoon was thirty-six years old and sick of Hollywood. Her acting career had slowed since her Oscar win in 2005; she had filed for divorce in 2006 and appeared in a few box office duds, and she wasn’t encouraged by the sexist, stultifying scripts she was receiving. Witherspoon requested meetings with studio bigwigs, and was disappointed to find that they didn’t care about developing stories with female leads. She decided that if she wanted big roles — challenging, substantive ones — she would have to create them herself. So Witherspoon, a prolific reader with an eye for woman-led page-turners, created a production outlet, and started looking for books to adapt. Two galleys caught her attention: a hiking memoir called Wild, and a thriller called Gone Girl. Enthralled by their gnarly depictions of femininity, she optioned both, and Witherspoon was reborn as a big-budget producer.

In the years since, Witherspoon has established herself as a media juggernaut, best known for her adaptations of dark, twisty books by and about women. Business Insider declared her the “queen of streaming” in 2020, referring to the increasing ubiquity of Hello Sunshine, her company dedicated to “shining a light on female authorship and agency,” on digital video platforms. “Women weren’t going to movies,” Witherspoon told the business magazine Fast Company in 2018. “Digital was winning. The only way was to go where women are, instead of expecting them to come to us in theaters.” One of Hello Sunshine’s most successful ventures has been Reese’s Book Club, which anoints new releases written by women with a buzzy social media campaign and a distinctive Hello Sunshine cover decal. The club has nearly two million followers on Instagram, and being chosen has been compared to “winning the publishing lottery.” For especially fortunate writers, the selection comes with a screen adaptation.

The most famous picks have been Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere, which Witherspoon chose for the book club and later adapted into a Hulu miniseries, and Where the Crawdads Sing, a debut novel by a retired scientist named Delia Owens, which held the Times bestseller list by the balls for more than a year. (The adaptation for that one is still in the works.) Few other selections have seen the level of commercial success that Fires and Crawdads have enjoyed, but like Oprah Winfrey before her, Witherspoon has the ability to transform authors’ careers with her stamp of approval.

In the many profiles that have chronicled her second act, Witherspoon has emphasized that her enterprise is not a fanciful vanity project, but instead the product of long-simmering exasperation. Though she embarked on her second career as a bountifully resourced industry veteran, her story has been written as something like an underdog narrative. Hello Sunshine and its wares are designed for women tired of “people thinking you’re something that you’re not,” or “incapable of something you are,” Witherspoon told The Hollywood Reporter. Comparing Witherspoon to Tracy Flick and Elle Woods, Ng told Fast Company, “People who underestimate her learn their mistake really fast.”

Witherspoon’s producing career predates the 2016 election, but the Trump presidency and its attendant conflagrations have supplied much of the affective atmosphere for her projects. Many books in the Witherspoon orbit are propelled, to varying degrees, by the much-discussed phenomenon of “women’s anger” — anger with idiotic men and the hollow promises of domestic life, with the traitorous cruelties enacted by other women, with the indignities of being overworked and underestimated. Witherspoon’s creative endeavors found a natural compatibility with the liberal feminist energy that animated the Women’s March, #MeToo, and Time’s Up, the last of which included Witherspoon as a prominent member. (The book club pick for July 2019 was Chandler Baker’s Whisper Network, a #MeToo workplace murder mystery that Witherspoon describes as “honest, timely, and completely thrilling.”) After the downfall of Hollywood’s most notorious predator-producer, she was poised to rise as a refreshing alternative.

Nearly a decade after she produced her first big-budget movie, it’s clear that Witherspoon has anticipated and mastered several major forces in the pop-cultural landscape: the book-to-streaming pipeline, the inexorable rise of the celebrity lifestyle entrepreneur, the widespread desire for narratives about women doing ugly things, attractively. The market for Witherspoon’s flavor of woman-led media has become impressively saturated, and her winning formula is best encapsulated by some of her splashiest book selections — Little Fires Everywhere, Where the Crawdads Sing, Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, Liane Moriarty’s Big Little Lies, and Cheryl Strayed’s Wild. What makes these five texts exemplary of Witherspoon’s broader creative endeavor is not just their commercial success but their conception of “female authorship and agency.” They draw their authority, and sense of urgency, from the intimation that women haven’t had the chance to tell the whole story. At first, the journey of the Witherspoon protagonist tends to align with Witherspoon’s producer origin story: she is dissatisfied with the roles society has provided for her, and itches for a different life. The stories diverge, of course, because the characters aren’t movie stars with a preternatural intelligence for the tides of women’s entertainment — their frustrations find release, not in career comebacks, but in acts of destruction and disappearance.

“Everyone in Shaker Heights was talking about it that summer,” begins Little Fires Everywhere, “how Isabelle, the last of the Richardson children, had finally gone around the bend and burned the house down.” The first chapter establishes the novel’s chatty suburban milieu and follows members of the Richardson family as they survey the remains of their home. Of particular interest is Elena Richardson, the matriarch, who observes the conflagration from her lawn, “clutching the neck of her pale blue robe closed.” From that moment alone, we know who Mrs. Richardson is. (Being cold in some sort of robe or shawl is the consummate rich lady gesture.)

Ng situates the incident within the economy of motherly work: Elena “had slept in on purpose, telling herself she deserved it after a rather difficult day.” The preceding day, we learn, involved some drama with Mia and Pearl Warren, the tenants of the Richardsons’ rental property down the road. The unexplained saga culminated with Mia and Pearl wordlessly leaving their keys in Elena’s mailbox and disappearing into the night. “Now it was half past twelve,” Ng explains, “and [Elena] was standing on the tree lawn in her robe and a pair of her son Tripp’s tennis shoes, watching their house burn to the ground.”

Like several books in the Witherspoon canon, Little Fires Everywhere operates in a quasi-forensic mode, beginning at the scene of a crime and tracing the perpetrator’s steps backwards. Gone Girl commences from the point of view of the titular character’s husband, Nick, in a chapter dated “The Day Of.” Big Little Lies starts in the home of a witness, Mrs. Patty Ponder, who hears screams and crashes from the school next door. (“That doesn’t sound like a school trivia night,” she remarks to her cat.) The prologue of Where the Crawdads Sing narrates the discovery of a dead man in a marsh. “A swamp knows all about death, and doesn’t necessarily define it as tragedy, certainly not a sin,” Owens writes. The reeking marsh, an inverse image of a lush, motherly earth, is personified as the murderer’s accomplice.

Even Cheryl Strayed’s memoir Wild, a book whose criminal activities are minor offenses relegated to flashbacks, adheres to this template. The book opens with the author explaining her decision to spend several months hiking the Pacific Crest Trail alone, in a passage that reads like she’s emptying her conscience. “There was the first, flip decision to do it, followed by the second, more serious decision to actually do it, and then the long third beginning, composed of shopping and packing and preparing to do it,” Strayed writes. She leaves her job in Minneapolis, finalizes her divorce, bids her friends farewell, and drives across the country to finish the deed, “at which point, at long last, there was the actual doing it, quickly followed by the grim realization of what it meant to do it, followed by the decision to quit doing it because doing it was absurd and pointless and ridiculously difficult and far more than I expected doing it would be and I was profoundly unprepared to do it.”

In Witherspoon’s chosen books, the question at hand is rarely, “Who did it?” but rather, “Why did she do it?” The texts are permeated by a certain weariness: women chafe under ideals of family and femininity, tire of the performances that their positions demand, and snap under the pressure. (Think of the iconic “Cool Girl” monologue, arguably the most enduring legacy of the Gone Girl franchise.) The universal grievance is the tyranny of types — this type of girl, that type of woman — and the struggle to define oneself in excess of their constraints. It often comes down to mothering, or in some cases, a lack thereof.

A subset of Witherspoon picks belong to a category that one might call the diminutive gothic, whose ironic suggestions of smallness (Gone Girl, Big Little Lies, Little Fires Everywhere) and closely observed depictions of middle-class family life offer answers to the implicit question: “Why would women with such nice, boring lives make such crazy decisions?” In these texts, suburban discontent is sinister rather than melancholy. “Mothers took their mothering so seriously now,” observes a witness in Big Little Lies. “Their frantic little faces. Their busy little bottoms strutting into the school in their tight gym gear… And they were all so pretty.”

Both Big Little Lies and Little Fires Everywhere allow us into the mind of the overzealous mother figure, whose compulsions belie her deep dissatisfaction with her own life. In the screen adaptations of both books, Witherspoon gamely portrays the shrill busybody — in Little Fires Everywhere, Elena, in Big Little Lies, Madeline. Both franchises also provide her with a free-spirited opposite — in Little Fires Everywhere, it’s Mia, the mysterious new artist in town, and in Big Little Lies, it’s Bonnie, the ex-husband’s second wife — and the two figures circle each other like magnets, with the insider straining to discern the interloper’s intentions. Neither book explicitly characterizes this dynamic as one of racial animus, but both screen adaptations introduce the possibility by casting black women — Kerry Washington as Mia, Zoë Kravitz as Bonnie — as the foils to Witherspoon’s alpha-moms. The Witherspoon characters embody some of the most grating stereotypes about affluent white moms: artificial niceness that barely masks overbearance, obsession with matters that seem trivial to everyone else. In these tense, gossipy settings, mothering is an object of endless scrutiny, but it also supplies a disciplinary, censorious way of seeing: women and girls are assigned their types in the matrix of motherly judgment.

Moriarty, who is Australian, takes a bitchy, satirical approach to her subjects (“That’s enough now, Mummy,” says a precocious girl in Big Little Lies), while Ng writes clear-eyed parables of American life. Elena serves as the standard bearer for white suburban orthodoxy in Little Fires Everywhere, and every other character is subject to her assessment. She hates her younger daughter, Izzy, for being a rebellious teenage jerk. She hates Bebe Chow, a Chinese immigrant fighting for custody of her baby in family court, for being poor and making bad decisions. Most of all, Elena hates Mia for being insufficiently jealous of her life and for making art that she doesn’t understand. (“Artists, [Elena] reminded herself, didn’t think like normal people.”) Lest you dismiss Elena’s resentments as petty and ineffectual, she does everything she can to corral the people she deems unfit, including hiring Mia as a housekeeper — indeed, Elena hates Mia so much that she decides to become her boss in addition to being her landlord. By the end of the book, Mia, Bebe, and Izzy have all fled the suburb, or have been successfully purged from it, depending on how you look at it. The twist, of course, is that even Elena suffers under her own stringent paradigm, though she doesn’t realize it until it’s too late.

Yet the absence of the mother figure threatens a similar encroachment of type: the motherless protagonists of Where the Crawdads Sing and Wild are reduced under stereotypes of the fringe and marginal. The original sin of Crawdads is an act of maternal abandonment: after the prologue, the book jumps back several decades, to a six-year-old girl named Kya Clark watching her mother leave their family’s backwater shack in fake alligator high heels, “her only going-out pair,” never to be seen again. After Kya’s mother leaves, other family members follow suit until Kya is left to raise herself. She forgoes formal schooling, survives on the charity of Jumpin and Mabel, a black husband and wife who clothe and feed her with donations from their church in “Colored Town,” and becomes something of an urban legend among children in town — the “Marsh Girl.” In the absence of a mother figure for Kya — Mabel is more a flat stereotype than a real character — Owens directs us, again, to the personified swamp: “Kya laid her hand upon the breathing, wet earth, and the marsh became her mother.”

Strayed, who ventures into the wilderness as a way of coping with her mother’s death, never identifies such a substitute, but it’s implied that she is exercising freedoms that were never available to her mom. “I’ve always been someone’s daughter or mother or wife,” Strayed remembers her mother saying after the fatal diagnosis. “I’ve never just been me.” On the trail, Strayed is no one’s wife or daughter, but she quickly becomes aware of her new role in a diffuse society of hikers — she is a woman traveling alone, which invites both suspicion and concern. Strayed readily classifies the men she meets as recognizable types — the New England blue blood, “charmingly sure of his place at the very top of the heap,” or the northern Minnesota guy, “searching and open-hearted” — but balks at being categorized herself. She spars with a hippie journalist named Jimmy Carter (no relation) who insists on describing her as a hobo. (“Being a hobo and being a hiker are completely separate things,” she insists.) When a trucker asks, “What kind of woman are you?,” she squirms.

Strayed’s thousand-mile hike might be best understood as a quest for narrative control. (The poetically apt “Strayed” is not the author’s given or married surname; she chooses it while filling out divorce paperwork.) She is a writer, and makes room in her heavy pack for books, burning chapters as she finishes reading them in order to lighten the load. It’s fitting that many of the women Witherspoon canonizes have literary and artistic ambitions: their deceptions are acts of creation, and vice versa. We first meet Amy Dunne, a writer and the titular “gone girl,” through her diary entries, which we later learn are fictionalized to frame her husband for her disappearance. Elena and Mia of Little Fires Everywhere are opposites in both disposition and creative output: Mia, the nomadic artist, makes “eerily beautiful” objects out of doctored photographs, reassembled furniture, and secondhand stuffed animals, while Elena inexplicably wears “high-heeled pumps” to work as a reporter for a free community newspaper, covering “city council meetings and zoning boards and who won the science fair.”

Elena feels unfulfilled by her work and pursues something she sees as more rewarding: digging into Mia’s past under the guise of journalistic investigation. She tracks down Mia’s estranged parents and learns that Mia conceived Pearl as a surrogate for a wealthy couple. (She lied about having a miscarriage and has been hiding from the adoptive parents ever since.) This discovery, among other intrusions, drives Mia out of Shaker Heights for good. When she flees, she leaves behind an envelope of symbolic photographs, one for each of the Richardsons, all images of repurposed objects they have discarded: a modified reproduction of Lexie’s discharge form from an abortion clinic, a hockey chest pad with plants growing from it for the perennially guarded Trip, a flock of origami birds for forgotten middle child Moody, a magnetic compass made from one of Mr. Richardson’s collar stays, and, for Elena, a shattered birdcage, cut from one of her articles in the newspaper, with a single golden feather in the center. Ng depicts Mia’s climactic work of art as therapeutic and didactic, a moving last act of service for the Richardsons, as well as a way of getting the last word.

Perhaps the most poignant artistic journey is that of Crawdads’s Kya, who learns to read as a teenager, thanks to the kindness of a young man named Tate Walker. They start their lessons with an almanac, and Kya reads her fateful first sentence: “There are some who can live without wild things, and some who cannot.” Tate and Kya’s relationship quickly becomes romantic, and literacy gives Kya new mastery of her circumscribed world. She learns her parents’ proper names when she sees them inscribed in the family Bible, and she is finally able to label her vast collection of marsh specimens. She also discovers a passion for poetry, and the rest of the book is punctuated with Kya’s recitations of thematically appropriate verses by a writer named Amanda Hamilton.

The drama that carries the second half of the novel involves a love triangle, a death, and a book deal. When Tate breaks up with her, she attempts to fill his absence by dating the boorish Chase Andrews, who lies about his engagement to another woman and attempts to rape Kya when she ends the relationship. After returning from college, Tate leverages his new connections to score Kya a contract for writing reference books about seashells and the two of them reconcile. The book advance subsidizes a makeover for Kya’s decrepit shack, and everything seems to be perfect, until Chase’s body is discovered in the marsh, and Kya is accused of pushing him to his death. Kya has an alibi — she met with her book editor in Greenville on the night Chase died — and her lawyer convinces the jury that the prosecution is weaponizing the community’s prejudices against the “Marsh Girl” to convict an innocent woman.

The ending, which takes place after Kya’s elegant natural death at the age of sixty-four, can only be described as “you have to be fucking with me.” Looking through his deceased wife’s possessions, Tate discovers a shell necklace that proves Kya did, in fact, kill Chase. He also learns that Kya had been secretly publishing poetry under — you guessed it — the pseudonym Amanda Hamilton, and reads one last verse that narrates the murder: “Down, down he falls, / His eyes still holding mine / Until they see another world.” Kya’s science writing supplied the alibi for her revenge; in her posthumous poetry, she gloats that she got away with it. Through this revelation to the reader, the author gives Kya the recognition she never received in her lifetime. It’s a baldly ridiculous plot twist, but it’s also a redemption arc for the female artist: to be recognized is good, and to be underestimated and recognized later is even better. When Tate burns all of Kya’s papers in a fit of disbelief, it almost seems beside the point.

The ending of Crawdads is similar to those of Gone Girl and Little Fires Everywhere in its deployment of a particular trope: the woman whose genius is kept secret. Gone Girl concludes with Amy writing a book, but her true masterpiece is the fiction of her married life: Amy makes herself pregnant by stealing Nick’s sperm sample from a fertility clinic and threatens to keep his child away from him if he doesn’t meet her demands, which include the destruction of a memoir that would have incriminated her. (“He is learning to love me unconditionally, under all my conditions,” she writes.) In Little Fires Everywhere, when the Warrens drive away from Shaker Heights, Pearl asks her mother, “What if those were the pictures that were going to make you famous?” Ng intimates that Mia eventually achieves renown for another work, — something that’s “just a wisp of an idea” at the moment of the family’s escape — but the Richardson photos are, of course, the most valuable to us as readers. We are meant to relish the knowledge that the photos become “uneasy family heirlooms,” sitting in the attic to be discovered by later generations.

In pop-feminist discourse, there are few motifs more salient than the secret knowledge of women — the men whose names have coasted through the whisper networks, the slights that would be undetectable to the untrained eye. Unfortunately for women, it’s a rather sexy motif. The highly lucrative project of telling women’s narratives seems to work in direct opposition to the systems that keep women silent, but really, the two shakily move in tandem. Women’s stories matter because women’s stories have never mattered; the endeavor of telling them would carry less weight were it not attended by the threat of the alternative. Show me a tale about a woman almost forgotten by history, and I’ll click it. There’s no better way to sell a story than to say it nearly went untold.

Marella Gayla is a contributing editor at The Drift and a member of The New Yorker’s editorial staff.