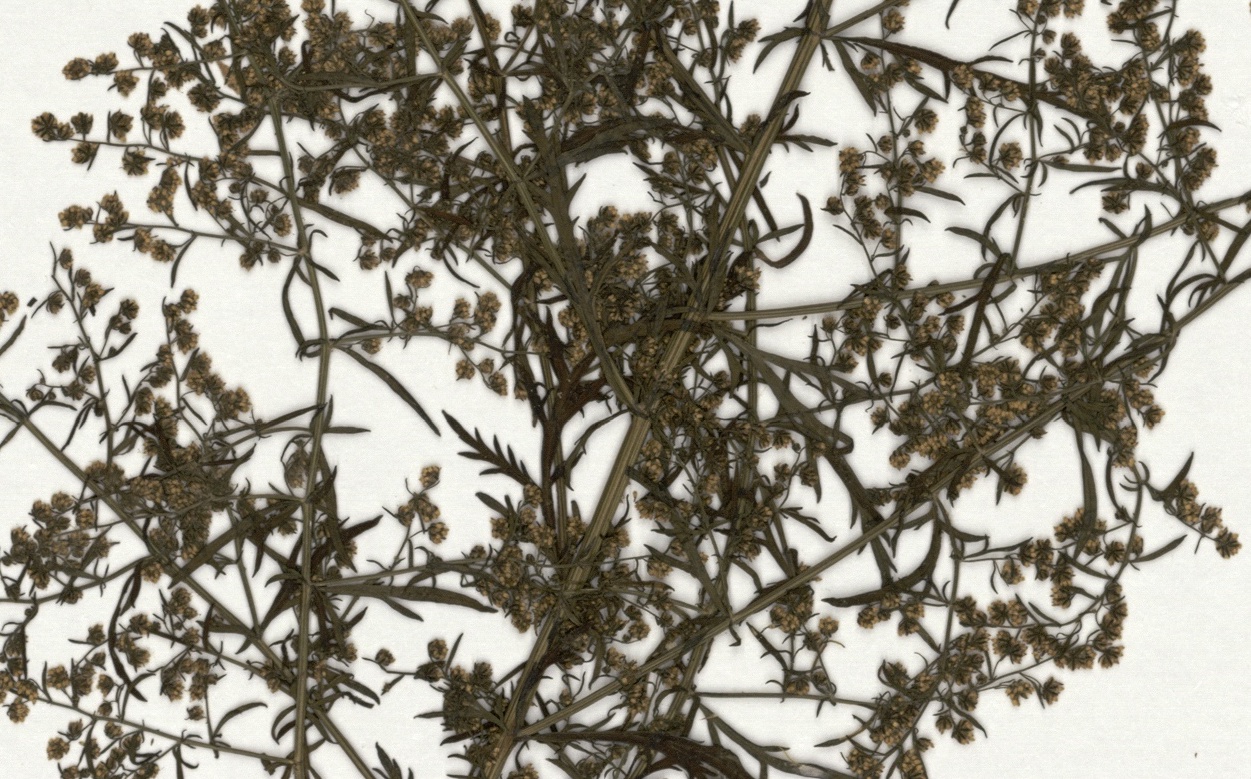

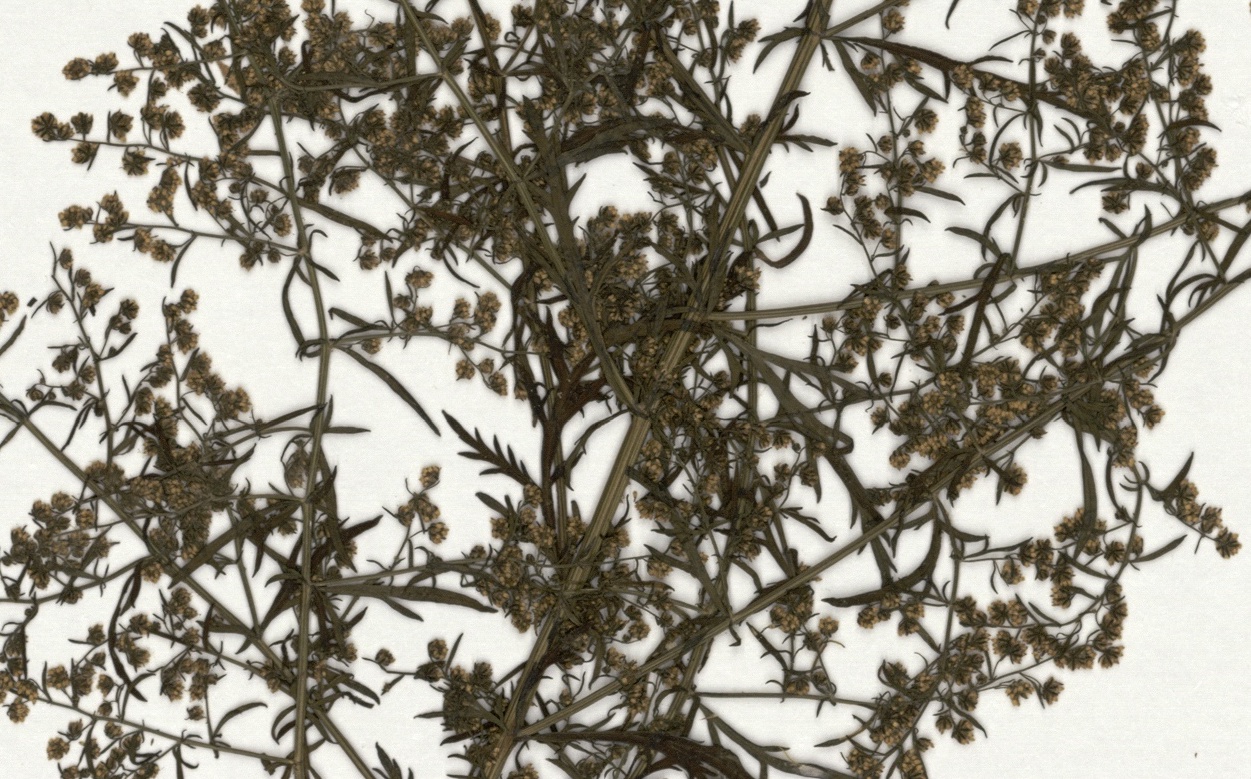

Artemisia annua. Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris (France) Collection: Vascular plants (P) Specimen P04339543

Artemisia annua. Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris (France) Collection: Vascular plants (P) Specimen P04339543

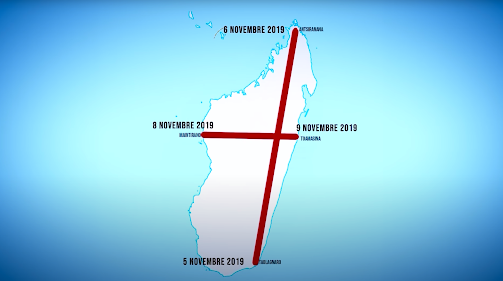

On March 16, Madagascar’s state-owned TV station aired an 18-minute documentary. Narrated by two airline pilots, it re-enacts a November 2019 visit to the island nation by an anonymous Brazilian woman purported to be a prophet. “Joana,” as she is dubbed in the film, crosses the island in two flights, one south-to-north and the other east-to-west, tracing the shape of a crucifix. She has been sent by God, she confides in the pilots, to make a protective cross over Madagascar, and to deliver a warning. The world would soon be besieged by biological warfare, she predicts, and Madagascar alone held a remedy that could protect the Malagasy people and bring desperately needed economic relief to a country where 75 percent of the population lives below the international poverty line. There was one condition: the people had to reaffirm their belief in God.

Over an image of the statue of Christ the Redeemer in Rio, Joana calls on the majority-Christian nation to double down on faith. Flashes of coronavirus panic — statistics, hospital rooms, body bags rolling down a hill in Italy — fade into a close-up of Joana’s face as she cries crocodile tears.

Enter Andry Nirina Rajoelina, Madagascar’s President, who reassures viewers that they will be protected from Covid-19 and insists that the island “manana fanafody” (“has medicine”). In the film’s concluding montage of stock images, a Malagasy woman is seen in a field harvesting rosy periwinkle, an indigenous plant used globally in cancer drugs.

Four days after the documentary aired, the first cases of Covid-19 surfaced in Madagascar. Two women had returned from a trip to France with the virus; another came from the neighboring island of Mauritius. That day, Rajoelina’s government suspended all flights, closed schools, and cancelled large gatherings. A full lockdown followed in the three largest cities, with military and police deployed. Those caught maskless were sentenced to public street cleaning in shame.

Three weeks later, Rajoelina announced that a potential, but confidential, remedy for Covid-19 was undergoing tests at the Malagasy Institute of Applied Research, Madagascar’s national laboratory for the development of traditional herbal medicines. The cure, he declared on Twitter, would “change the course of history in this global war being waged against the pandemic.”

By April 20, the miracle medicine had a name, Covid-Organics (CVO), and an eye-catching package: 330mL bottles labeled in the orange hue of the President’s political party. Speaking on national television, Rajoelina echoed Joana’s rhetoric. “Madagascar has been chosen by God,” he proclaimed, taking a big gulp of the beverage, its ingredients still undisclosed. “I will be the first to drink this today, in front of you, to show you that this product cures and does not kill.”

Rajoelina swiftly lifted lockdown measures, and CVO was distributed by military officers throughout the country and mandated for all students returning to school, striking up debates among the Malagasy people about whether or not to trust the government’s tonic. A friend confided that she kept the soap the government gave her and threw the CVO in the trash.

What came next was a hodgepodge of prophecy, faith, and medicine. Rajoelina called for Madagascar to embrace “clinical observations” rather than “clinical trials” in evaluating the drink. At the time of the announcement, two individuals had taken CVO and recovered from Covid-19. But for a virus with a recovery rate upwards of 90 percent, that statistic is effectively meaningless. When asked how he could be sure of the drink’s efficacy, Rajoelina answered confidently, “History will prove it.”

At the time of CVO’s debut, the global death toll from Covid-19 had just surpassed 100,000, but Madagascar still only had a handful of confirmed cases. By the end of April, the count had risen to 121, and in June cases spiked. A two-week lockdown was reinstated in July to little avail: the number of positive cases surpassed 14,000 in August. As of this writing, that number has climbed to 16,810, with 238 deaths.

Madagascar — a nation still plagued by the legacies of colonialism, slavery, corruption, and extractionist industry — would have been an unlikely pandemic hero. A home-grown Malagasy cure would have upended decades of exploitation of Madagascar’s biodiversity by the Global North, as well as the regimes by which local remedies and traditional wisdom are transmuted into commercial pharmaceutical products the world over. For a brief moment, CVO felt like a turning point, as leaders across Africa and the diaspora voiced support and placed orders for the drink. But the hype was short-lived. Instead, CVO became a case study in how colonial politics still determine the vectors of power and profit when it comes to medical knowledge.

Alternative remedies for Covid-19 have circulated furiously since March — from the Trump-endorsed hydroxychloroquine craze to Instagram debates about Echinacea and Ayurvedic treatments in India. But only in Madagascar have we seen an entire government fully adopt and promote a mysterious and minimally tested herbal cure. The island is a fitting setting for such an endeavor. Isolated from the African mainland, it is considered a biodiversity hotspot — one of only a handful on earth. Ninety percent of its plants and animals are endemic (native and exclusive to the island). This is a blessing and a curse: today, only 30 percent or less of Madagascar’s original natural vegetation remains, primarily because many native plant species are actively useful in agriculture, building, textiles, and — crucially — medicine.

The Malagasy history of traditional medicine, called fanafody gasy, dates back 2,000 years to the arrival of the island’s first settlers. Incorporating native plant and animal materials, fanafody gasy reaches beyond the Western conception of medicine. Demand remains high: The World Health Organization estimates that 80 percent of people in Madagascar use traditional Malagasy plant medicine. Sometimes, herbal remedies are taken in tandem with pharmaceutical drugs, but the majority of the Malagasy people live at least a two-hour walk from a Western healthcare clinic. Meanwhile, the nation continues to face malaria, polio, measles, flu, rotavirus, regional famines, and widespread chronic undernutrition. Outbreaks of the bubonic plague occur annually, as fleas on the backs of rats spread the deadly disease, which is often traced back to the nation’s overcrowded and unhygienic prisons.

Across the island, medicinal plant markets are meeting-places for medical advice and gossip, settings where health, magic, and social life overlap. A patient seeking a diagnosis might consult an ombiasy (spiritual healer), a renin-jaja (sage-femme/midwife), a bone-setter, a massage therapist, a biomedical doctor, or a trusted friend. And, according to the wisdom of these advisors, the illness might have a physical source, but it might also be traced to the psychic or social — caused by jealousy, heartbreak, or misfortune.

Rajoelina’s plan appealed to the national reverence for plant medicine, potent postcolonial nationalism, and ecological exceptionalism. He also ensured that he would profit personally. As he made sure to note publicly, it would be illegal to export the medicine or any of the plants used in the still-secret formula.

Africa’s youngest president, Rajoelina came to power in 2009 after he led a coup against his corrupt predecessor Marc Ravalomanana. In one particularly scandalous deal, Ravalomanana had arranged to lease half of the island’s farmable land to the Korean industrial company Daewoo for the next 99 years. Fed up with development projects that only benefited the elite, the masses rallied around Rajoelina’s agenda. The Malagasy Army stormed the royal palace, and Rajoelina declared himself President. In 2018, he was challenged by 35 candidates including Ravalomanana, but he held onto the seat.

In a nation where two-thirds of the population is under 25, it was not difficult for Rajoelina — a former entrepreneur who skipped college to become a DJ and event planner — to gain cultural cachet. His carefully curated image extends even to social media: he is photographed at parades in festive, traditional lambahoany tops, distributing food in rural villages, making speeches, and more recently wearing a mask as he oversees production of CVO.

The President made an international media splash with the unauthorized tonic, but many in Madagascar hesitated to touch it. Long used to propaganda, these citizens were unfazed by the Joana stunt. When asked directly whether the Joana documentary amounted to propaganda, Rajoelina’s chief of staff replied: “It is necessary to recognize that there are unexplained mysteries in the world.”

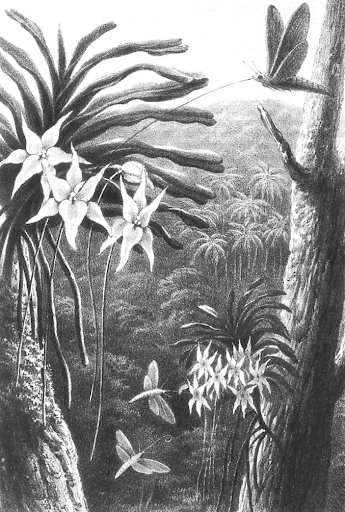

The unbelievable happens in Madagascar all the time, and largely falls under the radar of global attention. The 2009 coup, for instance, was one of the largest peasant land revolts in recent history. There are accounts of ancestral magic melting French colonizers’ bullets into water during the 1947 insurrection. A specimen of the Madagascar orchid Angraecum sesquipedale was crucial to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution because he deduced that a moth with a remarkable proboscis must have pollinated it. That the magical island might harbor a coronavirus cure seemed not entirely inconceivable — and Madagascar’s initial infection rates were miraculously, even suspiciously low.

For some, CVO’s arrival signalled an opportunity to build solidarity among African nations and push back on centuries of tense medical relationships with colonial powers. CVO was always an international project. With the English name “Covid-Organics” (it’s “CVO Tambavy,” in Malagasy) it was well-positioned to tap into the booming holistic wellness market, currently valued at $34 billion worldwide. (In local supermarkets, it sells for 53 cents; online it retails for $100 plus shipping.) But when French doctors began to talk about testing dubious cures on African populations, CVO began to look like a statement of anti-colonial defiance. Another medical abuse posing as a benevolence would not be tolerated by African people; if that meant experimenting with homegrown cures, so be it.

The possibility of forming diplomatic pathways to validate and market traditional medicine among African and African diasporic nations was an early boost to CVO’s appeal. Its first international customer was Senegal. Comoros, Chad, Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, Liberia, and Nigeria soon followed. In total, the leaders of a dozen African nations placed orders. Out of gratitude, the president of Haiti called for African diplomatic alliances “entre pays d’amis.” The President of Tanzania, John Magufuli, sent a plane to Madagascar to fetch the medicinal drink. Madagascar had “made Africans proud,” said the country’s foreign minister Palamagamba Kabudi. “Madagascar is providing… a solution to a global problem,” he added. “We are used to being told it is Europe and Western Europe and other countries who solve global problems.”

“What if this medicine were found in Europe? Would you doubt it so much?” President Rajoelina asked in an interview on France 24. “African and Malagasy scientists should not be underestimated,” he continued. “We are here… We have our own tonic.”

Despite Rajoelina’s nationalist rhetoric, only one known ingredient in CVO is native to Madagascar: Ravensara, a plant that’s already widely used and trusted across the island as a powerful treatment for respiratory conditions and extreme fatigue. But the primary active ingredient in the “enhanced traditional remedy,” as it has been marketed, is not African at all, but rather an Asian import called Artemisia annua.

Relations between China and Madagascar are tinged with colonialism: in 1972, diplomatic arrangements granted China access to drilling, mining, and fishing enterprises in Madagascar in exchange for development aid and medical support. Since 2015, China has been Madagascar’s biggest trade partner. A special envoy of President Xi attended Rajoelina’s inauguration in 2019. And it’s widely accepted among the people of Madagascar that Artemisia was “a gift from China,” but the details of its arrival remain murky.

Part of the daisy family, the Artemisia plant is green-yellow and fern-like in appearance. It is sometimes known as sweet wormwood or sweet sagewort, though both are misnomers. The plant itself is stinky. Its pungent odor comes from terpenoids, the organic chemicals also responsible for the smells of cinnamon and eucalyptus.

In China, where it is known as qing hao, the plant’s medicinal use dates back at least to the Ming Dynasty. Long forgotten, it was rediscovered in 1967 by Project 523, a secret Chinese task force charged with searching for a medication to fight malaria, which was a major threat during the American War in Vietnam. One branch of the group scoured ancient texts from Traditional Chinese Medicine, and their findings on qing hao led to the development of “artemisinins,” a class of drugs that has been found effective against malaria. Though the initial findings were met with skepticism in 1979, chemist Tu Youyou later won the 2015 Nobel Prize for her role in the process. Artemisinins are now, in combination with other medications that enhance their performance, part of the standard course of treatment for malaria. More than 64 million treatments are delivered annually to over sixty countries, including Madagascar — which, like several other African nations, now grows its own supply. On the island, Artemisia is used to treat malaria, fevers, and the flu.

While malaria and Covid-19 share many initial acute symptoms — fever, chills, fatigue, difficulty breathing, headaches — they are not scientifically related. Currently, both are responsible for death at global annual rates of over 400,000 people. While the spotlight is now on Covid-19, widespread infectious diseases such as malaria, HIV, and tuberculosis have not disappeared, especially in under-resourced nations.

The over-use of malaria cures for Covid-19 could not only prove ineffective, but also help breed treatment-resistant malaria strains, a key concern in the development of anti-malarial medications. If the President of a temperate climate nation unnecessarily takes hydroxychloroquine, for example, there is little public health impact. But in high-malaria zones, using a malaria treatment for Covid-19 could have lasting effects.

So who exactly stands to gain from touting Artemisia as a Covid-19 cure and ramping up production — particularly right now, and particularly in Madagascar? As it turns out, the timing and the source of the idea are both suspect: Artemisia is encircled by a complex web of international interests.

Rajoelina was initially tipped off to Artemisia’s potential as a Covid-19 cure by the orthodontist Lucile Cornet-Venet, who runs the Paris-based “Maison de L’Artemisia.” Since 2012, the organization has gained a foothold in 23 African countries while advocating for the use of Artemisia as a standalone malaria treatment, going against the recommendation of the WHO. The island’s Artemisia plantations are run by Bionexx, a French-owned quasi-pharmaceutical company that has established a network of 15,000 smallholder farmers across Madagascar, together producing about 2,000 tons of dry herb a year (100 kilograms of Artemisia yield roughly one gram of artemisinin). Due to increased availability, prices of artemisinin have dropped in recent years, and those who have run into difficulty touting Artemisia as a standalone cure for malaria are looking for other uses of the plant.

Absent from the list of parties that would directly benefit from increased production of the plant, of course, are the Malagasy people.

The invasion of Madagascar in the 1890s was arguably one of the worst medical failures in French military history. As during the American War in Vietnam, more soldiers died from malaria and other medical complications than in actual combat, leaving the French in urgent need of local medicinal resources — and the people who knew fanafody gasy. Even as the invaders portrayed traditional practices as backwards or savage, they simultaneously harvested local knowledge from the Malagasy people.

Today, the French use traditional medicine to fight on another front: aging. Luxury brands such as Yves Rocher and Clarins export Malagasy herbs for detoxification masks, anti-aging eye creams, and wrinkle-fighting lotions — all of which are sold at 150 times the price of the raw herb material in Madagascar, where they’re also used in highly effective face masks. Most Malagasy people share none of this profit, which is not unusual. Bioprospecting — the pharmaceutical industry’s search for novel materials in the traditional medicines of people around the world — is the primary process by which organic materials are selected for commercial products, and the gains rarely trickle down. Instead, traditional healers are cut out entirely.

Madagascar’s national laboratory for medicinal plant research, the Malagasy Institute of Applied Research (IMRA), was founded in 1957, three years before Madagascar won independence from France, to validate traditional therapeutic plant knowledge. That knowledge proved difficult to commercialize in a way that benefits the Malagasy people. IMRA’s director, Malagasy scientist and fanafody gasy authority Albert Rakoto Ratsimamanga, developed a topical healing ointment called Madecassol in collaboration with French scientists, and the product is now manufactured by Bayer and licensed by La Roche-Posay, a French luxury skincare company. More recently, the drug company Eli Lilly was accused of bio-piracy after using a plant native to Madagascar in two chemotherapy drugs. In both cases, ownership is unclear. A Malagasy-French research duo studied a foreign plant, and foreign researchers studied native ones — which patent should belong to Madagascar, if either?

Even with a patent, the flow of resources is unlikely to reach those who use the traditional medication on which these drugs are based. Lab work takes too long to be competitive; Internet outages are a regular occurrence in Madagascar. Ultimately, it’s not feasible for a single Malagasy-owned laboratory to alter the global pharmaceutical market in any large-scale way.

And even if it were financially possible to manufacture it in Madagascar, traditional medicine is difficult to formalize for a number of reasons. Soil type, harvesting style, and the portion of the plant used can all alter the potency and, therefore, the recommended dosage. Whereas synthetic compounds can be measured in laboratories, traditional medicines depend on centuries of accumulated knowledge. Even when these cures have earned local or national trust, they can’t be adopted internationally until they have been tested in evidence-based studies. Ayurveda, traditional Indian medicine, and traditional Chinese medicine are both used locally and around the world, but their value is never quite appraised on par with Western biomedicine. The more prominent traditional medicine systems tend to possess written pharmacopoeia documents (such as those consulted by Project 523), which are assembled by those in power to aggregate and distill the people’s knowledge, often for dissemination. Such documents have, over the years, been used as biomedical databases.

That is because prioritization of the written word is a companion of empire. In Madagascar, where most families have never left the island, the necessity to write down materia medica is only of concern for those needing to translate across cultures or generations. Each region of the island has its own pharmacopeia due to the dramatically different plants available in the many biomes. There are few texts, and those that are available are written in Sorabe, an Arabic-based alphabet.

Madagascar’s most noted pharmacopeia was compiled by Edouard Heckel, a 19th-century French scientist and member of the colonial navy who never once set foot on the island. From a chair in Marseille, he compiled missionary notes, botanical samples from colonial administrators, and hearsay to create Les plantes médicinales et toxiques de Madagascar (1903). The text, which includes both Linnaean classifications and Malagasy names for plants, illustrates the violent epistemology of colonialism. Heckel overwrote Malagasy medicinal knowledge with European scientific jargon, privileged French applications over those used by the Malagasy, and generated both profit and prestige for the Institut Colonial de Marseille and Marseille’s Colonial Expositions, which were used to showcase France’s colonial gains.

The distinction between medicine and ritual, science and magic, is an invention of 16th century Western Europe. Taxonomies followed shortly thereafter, and, by the 18th century, Carl Linneaus’s classification system had grown to encompass the entire living world. Taxonomies are not fixed and stable: they are contingent and historical, and they shift with the attention and priorities of their creators. Older family trees were often based on morphology, for example, while taxonomies now tend to rely on species’s genetic relationships.

While many consider biology neutral, a review of the names given to the natural world reveals deep cultural markers. The person who finds the species gets to play Adam and name it. Ask Diplodocus carnegii, a dinosaur species that had its bones named after its mission’s founder, Andrew Carnegie; Begonia darthvaderiana, named for Darth Vader; Dudleya hendrixii, for Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child;” the worm Khruschevia Ridicula, named out of distaste for former Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev; or the slime-mold eating beetle Agathidium bushi, named for George W. Bush. Onopordum acanthium, or the donkey fart thistle, only has meaning where donkeys roam, and Sansevieria trifasciata, or mother-in-law’s tongue, will have little significance for some.

Madagascar has its own botanical taxonomic classification system, which alternately overlaps with and diverges from the Linnaean method. Often taught orally, many of the names contain mnemonic devices or instructions, such as tsy maty (never die), or bemaimbo (very stinky). It is not uncommon for plants to have multiple names or for one name to refer to multiple plants. Across the island, these names also shift with local community needs, dialects and attitudes. Commiphora aprevalii is otherwise known as the vahaza (“foreigner”) tree. Its peeling, red bark is a reminder of what happens when fair-skinned wildlife tourists brave the island without sunscreen.

Africans and people of African descent have long distrusted foreign aid — medical or financial — for good reason. From phrenology to to the foundation of modern gynecology and syphilis research, Black people worldwide have been treated as test subjects to prod, maim, and murder. Under the guise of “civilizing” and “developing,” settlers committed medical violence through abusive testing and forced procedures. It’s no wonder that in some places across the continent, colonizers were identified as vampires in white coats who came for blood.

This deep suspicion of imperial biomedical sciences surfaced after Joana’s televised visit to Madagascar. Tweets, YouTube comments, and Facebook replies surged with African pride, anti-colonial sentiment, and hope. If Madagascar had pulled it off, CVO could have become a rallying cry for anti-colonial solidarity and for traditional medicine worldwide. It might even have signalled to development agencies that medical answers are not always imported. (Elsewhere on the continent, nations have seen many of their remarkable Covid successes obscured by lack of testing capacity and, therefore, ignored by much of the international community.)

But as the situation in Madagascar began to worsen, the nation traded its foreign export market for foreign aid. Over a summer that marked Madagascar’s 60th anniversary of independence from France, Morocco donated 8 billion face masks, foreign doctors flew in to support the overburdened medical system, and the African nations that had once proudly promised to purchase Madagascar’s cure began to reverse course. Senegal backtracked, clarifying that it had only agreed to receive samples, not prescribe them to its people. Tanzania claimed its shipments would be used for clinical testing, not distribution. Ghana, initially cautious, repeated that its purpose in ordering CVO was always to test it. Nigeria stated definitively that CVO could not cure Covid-19, and a science advisor to the Congo’s National Covid-19 Response Committee announced that an Artemisia study had found “no effectiveness in either prevention or treatment.”

So far, only the UK HealthCare’s Markey Cancer Center has conducted human studies on CVO, and one researcher has raised concerns over the dosage level and the continued lack of public disclosure of the beverage’s full ingredient list. The Democratic Republic of Congo has been testing Artemisia alone, without the rest of the ingredients in the CVO beverage. While many in South Africa have mocked Madagascar, the country has started pouring funds into researching Artemisia afra (African wormwood), a close relative to Artemisia annua.

It is not entirely off-base to imagine that the plant could prove useful in fighting Covid-19. In a 2005 Chinese study, 200 medicinal herb extracts were examined for action against SARS, and Artemisia showed promising effects in inhibiting the virus in a petri dish. Given the similarities between Covid-19 and SARS, this lead garnered attention in scientific communities around the world. ArtemiFlow, a company that seeks to develop new artemisinin-based cures, recently undertook a study on the use of Artemisia against Covid-19, sourcing plant materials from a Kentucky-based company.

Whether the petri-observed effects can be reproduced in actual patients remains unclear, and the drug may simply need more time — herbal medicines, like vitamins, can take longer to be effective than hyper-potent synthetic drugs. These plants are non-toxic and can be less invasive, but require large doses and clinical trials. And in a pandemic, few are sufficiently patient.

The stakes of Rajoelina’s Covid-Organics scheme were obvious. Madagascar was already on the political margins of Africa, and an abrupt halt in ecotourism precipitated an outright crisis. All 43 protected area national parks, which bring in roughly $2 million USD annually, have been closed since March. Even in the absence of a global pandemic, Madagascar faces significant vulnerabilities like food insecurity; it is the world’s fourth (and Africa’s most) susceptible nation to climate disasters such as floods, cyclones, and droughts. The World Bank has provided $75 million USD to Madagascar, flagging the concern that the crisis “could reverse past progress in poverty reduction and deepen fragility.”

Jumpstarting Artemisia cultivation offered an opportunity to provide work on extant plantations while positioning Madagascar at the center of the pandemic, and Rajoelina, eager to turn a profit by any means necessary, preyed on the desire for local treatment and called it the people’s medicine. Meanwhile, as development dollars and political attention have been redirected to Covid-19, the leading morbid conditions in Madagascar remain neonatal disorders, diarrhea, malnutrition, and malaria — a disease against which Artemisia has actually proven effective. But with Madagascar’s Artemisia plantations repurposed to fuel CVO, a likely ineffective treatment, there is a strong possibility that Artemisia will not be in necessary supply.

The Malagasy government is far from reaching consensus on CVO: the Minister of Health (previously the Minister of Fisheries, president of the Malagasy Football Federation, and a senator) was sacked for requesting foreign medical aid, and most recently, the Minister of Communication has been imprisoned for protesting CVO.

But despite the corruption, ineptitude, and hokey marketing, Rajoelina’s plan seems to have worked — albeit not in the way he intended. When CVO was first introduced, deeply held anxieties about traditional medicine caused rumors to swirl on Internet forums and in smaller African newspapers, even beyond the island’s borders, that the WHO paid $20 million to squash the project, or that Trump had, or that China had poisoned the beverage stock. For a time, it was speculated that the Malagasy government would leave the World Health Organization after it refused to accept Covid-Organics as a legitimate treatment. Instead, quite the opposite has occurred.

In September, in a direct response to Rajoelina’s campaign, a WHO committee endorsed a protocol to expand and encourage clinical trials for traditional medicine against coronavirus. “If a traditional medicine product is found to be safe, efficacious and quality-assured,” regional WHO director Prosper Tumusiime said, “WHO will recommend (it) for a fast-tracked, large-scale local manufacturing.” This month, with millions of bottles of CVO still in stock — and still awaiting scientific support — Rajoelina opened PHARMALAGASY, Madagascar’s first herbal medicine factory tasked with producing CVO and CVO+, the new capsule version of the herbal drink. It has already received congratulatory support from the nation’s WHO representative.

Chanelle Adams is a researcher, translator, and writer based in Switzerland.