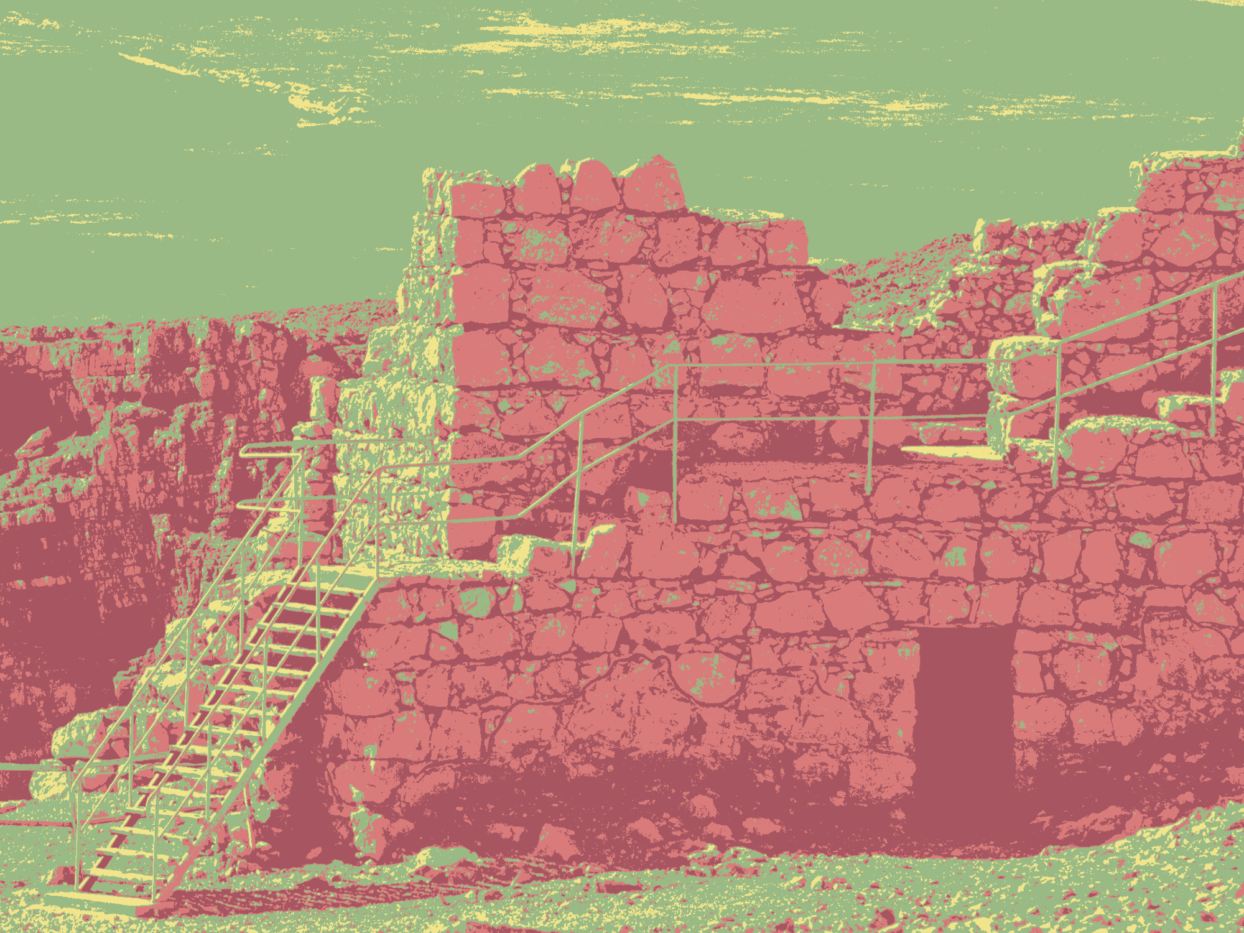

Image by John Kazior. Source image credit: Andrew Shiva / Wikimedia.

Image by John Kazior. Source image credit: Andrew Shiva / Wikimedia.

On December 15, 2023, an Israeli sniper operating in the Shuja’iyya neighborhood of Gaza City opened fire on three shirtless, unarmed men in their twenties, one of whom was waving a white flag. Two were killed instantly; the third fled into a nearby building, where he called out for help in Hebrew. He was discovered there by another IDF patrol, which shot him dead. At the time, there was already ample evidence of major war crimes perpetrated by Israeli soldiers in the Gaza Strip — only two days earlier, for example, credible reports had emerged that the IDF had executed a group of Palestinian civilians sheltering on the grounds of a school near the Jabalia refugee camp. But the Shuja’iyya incident provoked special outrage, with small demonstrations in Israel. The victims, it turned out, were escaped Israeli hostages.

An IDF massacre of Israelis was, by then, hardly an aberration. In fact, some of the first noncombatants targeted by the IDF in response to the October 7 attacks were Israeli hostages, thanks to a now-infamous protocol that permits the IDF to fire on its own soldiers. Though Israeli officials had announced in 2016 that the Hannibal Directive (named, it is reasonable to presume, for the Carthaginian general who died by suicide in the second century B.C.E.) would soon be phased out, it was deployed in at least three locations on October 7, per investigations by the United Nations and Haaretz. In one instance, the IDF killed an elderly hostage by firing into her captor’s vehicle from a helicopter. In another, an Israeli tank shelled a house in Kibbutz Be’eri, killing thirteen captives inside. On a November 2023 episode of Haaretz’s podcast, an IDF officer, Lieutenant Colonel Nof Erez, called the day’s maneuvers a “mass Hannibal.”

The Hannibal Directive has been a part of Israeli military doctrine since 1986, after a series of hostage crises involving Hezbollah and other paramilitary groups induced the IDF to develop a new internal playbook. The directive’s precise details aren’t known; Israeli military censors have prevented their publication. But the philosopher Asa Kasher, who wrote the IDF’s code of ethics, described Hannibal this way at a 2015 conference: “Better a dead soldier than an abducted soldier.” In practice, the directive is deployed more expansively than Kasher’s framing would suggest. “Better a dead Israeli,” a more honest formulation might read, “than an abducted Israeli.”

The “mass Hannibal” of October 7 reflects the ruthlessness of Israel’s martial conduct, but it also manifests a deeper pathology. Scholars and analysts, both on the ground and abroad, have observed that Israel’s recent conduct has been not only wildly murderous toward Palestinians, but also actively detrimental to Israel’s own safety and stability. Rashid Khalidi, a leading historian of the Middle East and the author of The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, remarked in a 2024 interview that, because Palestinians are “not going to lie down and let you walk all over them,” any politician “who takes Israel into Gaza without an endgame is suicidal — is a masochist.” The journalist Asa Winstanley, writing in The Electronic Intifada, observed that “many Israelis seem willing to sacrifice their own civilians on the altar of Zionism.” As Israeli strikes on Lebanon escalated, the Palestinian human rights attorney Noura Erakat wrote on X that “Israel will destroy itself and the entire edifice of a post-WWII global order.” Noah Kulwin, a host of the “Blowback” podcast (and a former Drift editor), phrased it especially colorfully: “Israel is putting a shotgun in its mouth,” he wrote on X last year, after the assassination of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, “and reaching around for the shells.” Yoav Rinon, a Hebrew University of Jerusalem professor, has written that Israel is in the process of something “akin to suicide.”

Very few (if any) governments in the postwar period have depended as profoundly as Israel’s on a certain luster of moral legitimacy and international goodwill. Israel needs Western money, Western trust, and Arab cooperation, but if the country’s current leaders were engaged in a deliberate and systematic program to invite worldwide loathing, one would expect their strategy to look much like it has over the course of the last two years. This is especially baffling given trends in public opinion even before 2023. As early as 2021, a shift in perceptions of Israel was underway; UCLA professor Saree Makdisi wrote in his book Tolerance Is a Wasteland (2022) that Israel’s bombardment of Gaza that year had “stripped the Israeli state project ever more bare of all those layers of denial, equivocation, and mystification with which it has cloaked itself for decades.” Millions protested for Palestine at the time, and, Makdisi added, “even in the halls of the U.S. Congress, the word ‘apartheid’ was uttered.”

After October 7, so was the word “genocide.” Among the sitting members of Congress who have said Israel’s attack on Gaza qualifies as genocidal are Bernie Sanders, Ilhan Omar, Rashida Tlaib, and Marjorie Taylor Greene. This summer, a majority of Senate Democrats voted in favor of a resolution, proposed by Bernie Sanders, to block some arms exports to Israel, a dramatic shift from the party’s stance just two years ago and a staggering one in the broader context of 21st-century American politics. The rest of the world is further along. Colombia, Nicaragua, and Turkey have vowed to break off diplomatic relations with Israel, and several more countries have withdrawn their ambassadors. France called for a partial arms embargo against Israel, and Germany promised to restrict weapons exports. France, Canada, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Spain, Ireland, and Norway — in all, 157 of 193 U.N. member states — announced their recognition of Palestine. South Africa, with the vocal support of China, Pakistan, and dozens of other states, brought a genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice.

In the last two years, Israel has committed a series of (almost) universally acknowledged crimes against humanity. Israel’s military has engaged in flagrant violations of international law, which forbids such acts as the destruction of civilian dwellings for no military purpose, the use of starvation as a weapon of war, and the annihilation of civilian healthcare facilities. The IDF massacred Gazans in line for food. It assassinated journalists and aid workers. It oversaw systematic rape and torture at the Israeli prison camp in Sde Teiman. Countless images of mutilated Palestinian bodies, including those of infants and children, have circulated in the last two years.

Israel’s right-wing leadership claims the war is essential for the country’s survival, but it may yet become obvious that the massacre in Gaza has permanently undermined the conditions that enable that very survival. In attempting to make sense of this contradiction, commentators frame Israel’s self-destructive provocations as strategic miscalculations, symptoms of paranoia, or evidence of Netanyahu’s desperate struggle to remain in power. But masochistic and even suicidal fantasy has always accompanied Israeli violence.

According to Professor Rinon, whose 2024 piece in Haaretz bore the headline “The Destructive Wish for Revenge Followed by Suicide Is Rooted in the Israeli Ethos,” that ethos is grounded in the myth of a few “suicidal lunatics who barricaded themselves on a hilltop.” Indeed, nearly every Israeli schoolchild is brought on a field trip to Masada, the mountain fortress where, in the first century C.E., Judean rebels known as the Sicarii barricaded themselves against the Roman army. When the Romans, using Jewish slave labor, began building a ramp up the side of the stronghold, the Sicarii chose death over enslavement. Because suicide was a serious religious taboo, the men drew lots and stabbed each other and their families, leaving only the last man to kill himself directly.

That, anyway, is the standard narrative. Its sole contemporaneous source is Flavius Josephus, a Jewish historian who, in the course of the war he would later chronicle, surrendered to the Roman occupiers and began to integrate himself into their society. As part of his larger rhetorical and scholarly project of revising Jewish history for Roman consumption, Josephus rendered the Masada episode in the standard style of the time, including concocted theatrical monologues. Most memorably, he invented a speech in which the Sicarius commander convinced the besieged (save for the few women and children who hid and recounted the tale) to leave the Romans “an example which shall at once cause their astonishment at our death, and their admiration of our hardiness therein.”

Before the advent of political Zionism, Josephus’s histories were largely ignored by Jewish religious authorities. While the rabbis of the Talmud discussed the first-century destruction of Jerusalem at length, they never mentioned Masada by name. (If they were familiar with the story, they may have considered its climactic mass suicide too obviously a violation of Jewish law to be included in the post-Biblical canon.) But early Zionists regarded the Rabbinic traditions developed in exile as embarrassingly submissive, disclosing too much of the will to live and not enough of the will to power. Josephus’s Masada became a powerful source text for the Zionists’ own Romantic nationalism. Beginning in the late 1920s, Ashkenazi migrants to British Mandatory Palestine visited Masada in the pilgrimages they made to concretize their connection with the land. As the scholar Robert Alter wrote in a 1973 Commentary article, the tale’s prominence in Israeli life can be attributed in part to the Hebrew-language writer Yitzhak Lamdan, who dramatized it in a 1927 book-length poem. The text, which rapidly became influential among pre-state colonists in Palestine, introduced a phrase which for decades would be repeated at Masada by members of the Israeli Armored Corps at swearing-in ceremonies: “Masada shall not fall again.” That “again” — which implicitly effaced the millennia of history between a siege against Jews in the first century and the establishment of a Jewish state in the twentieth — accounts for much of the line’s ideological power.

Since the establishment of the state of Israel, Masada has become integral to Israeli nationalism. This is thanks in large part to the efforts of the archaeologist and military commander Yigael Yadin, who conducted digs at the site in the 1960s. Yadin belonged to the first generation of state-building Zionists, serving in the Haganah (the paramilitary force that became the IDF) during the 1947-1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine and helping to organize the ethnic cleansing of Arabs from parts of Palestine captured by Zionist forces. He was an architect of 1948’s Operation Cast Thy Bread, which entailed the contamination of wells in Palestinian villages and towns with typhoid germs to prevent Palestinians from remaining in or returning to their homes. Israel’s leaders were obviously impressed: in 1949, he was appointed chief of staff of the IDF. Even after he retired to pursue archaeology, he continued to advise Israeli politicians (most notably in the lead-up to the Six-Day War), eventually forming his own political party and becoming deputy prime minister.

Yadin seems to have regarded his scholarly activities, including the excavation of Masada between 1963 and 1965, as a continuation of his state-building efforts. In her 2019 book Masada: From Jewish Revolt to Modern Myth, Yadin’s student Jodi Magness noted that he employed IDF officers in the dig and required participants to adhere to a military schedule. While some scholars have questioned the reliability of Josephus’s version of events, doubting that mass suicide really took place at Masada, Yadin seems to have taken it as fact. “Yadin closely followed Josephus’s account in his interpretation of the remains at Masada,” Magness wrote, “and attempted to reconcile apparent inconsistencies.” He was quick, for example, to identify human remains at the site as those of the Jewish zealots detailed in Josephus’s story, despite the fact that the intermixing of pig bones with said remains seemed to indicate that they belonged to later, non-Jewish occupants of the fortress.

The Israeli government, naturally, favored Yadin’s interpretation. In 1966, the same year Yadin published his book about Masada, Israel declared the site a national park. From that point on, official narratives presented Yadin’s reading of the excavated evidence as the truth. The bones he had identified were buried in 1969 with military honors, an absurd assertion of perfect continuity between the modern and classical periods. Today, an English-language park brochure claims that “in spite of the debate surrounding the accuracy of” Josephus’s account, “its main features seem to have been born [sic] out by excavation.” Israel’s first UNESCO World Heritage site, Masada is one of the country’s most popular tourist destinations, visited by hundreds of thousands of people per year before Covid and October 7 (when Israel’s tourism industry saw a precipitous decline). A 2020 blog post from the Birthright Israel Foundation, whose trips aim to convert young diaspora Jews into lifelong Zionists, claims that “nearly every Birthright Israel participant tells us that the sunrise hike to the top of Masada is one of the highlights of their journey.” At the site, the foundation asserts, “it is inspiring for Birthright Israel participants to learn about our people’s long history of resistance.”

Though Masada’s centrality in the Israeli national myth now goes virtually unquestioned, critiques were once commonplace in mainstream Western discourse. In 1971, after Israel declined the opportunity to make peace with Egypt and Jordan — the deals on the table included territorial withdrawal in exchange for diplomatic concessions — the American journalist Stewart Alsop wrote a Newsweek column accusing Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir of political malpractice. Alsop’s source, who remained unnamed, told him, “Golda has the Masada complex.” Two years later, Alsop reported that Meir had addressed this diagnosis at a Washington presser. “It is true,” she told Alsop. “We do have a Masada complex. We have a pogrom complex. We have a Hitler complex.” For Meir, a Masada complex meant simply the persistent consciousness of external threats to Jewish existence — threats were out there, providing meaning by way of menace to Israelis, who huddled quietly in here. But the Prime Minister didn’t seem to pick up on Alsop’s implication.

The Masada complex wasn’t just a backhanded way of talking about Jewish paranoia. It was an articulation of the idea that the Israeli government was, consciously or unconsciously, acting to bring about situations in which the country was surrounded and besieged. As Alsop wrote in the same 1973 piece, “To the horizon, it is easy to see that Israel can hold what it has. But beyond the horizon, it may be that Israel is creating its own Masada.” Only seven months after the exchange with Meir, Israel’s contemptuous dismissal of Arab diplomatic overtures indeed led to a war that mainstream historians regard as the closest Israel ever came to comprehensive defeat: in October of 1973, a coalition of states led by Syria and Egypt launched a surprise attack, on Yom Kippur, in an attempt to reconquer territories captured by Israel in 1967.

Zionism has, from the beginning, been animated by conscious and unconscious images of disaster. First as a body of ideas and then as a movement, it inherited and secularized the expectation, informed both by Jews’ understanding of themselves as the “chosen people” and by historical experience, that, at least until the final divine redemption, they would be made to endure periodic outbursts of annihilatory violence. A passage from the Haggadah, the text read by Jews at the Passover seder, gives this attitude succinct expression. “In every generation,” one translation pronounces, “they rise up against us to destroy us; and the Holy One, Blessed be He, saves us from their hand.” Zionism consists in accepting the first half of this passage but rejecting the second: expecting only malice from the world, but despairing of any protection, or any justice, from God.

Early Zionist thinkers like Max Nordau, who preached Muskeljudentum (“muscular Judaism”) and advocated the practice of gymnastics and other sports for young Jews, expressed the Zionist idea explicitly in terms of the rehabilitation of the individual Jewish subject and his physicality. The neurotic, landless nebbish of both the antisemitic and Zionist imaginations was to be replaced by the new Jew: physically fit, confident, and bound up with the soil. This archetype is in some ways a remnant of Zionism’s historic ties to the Romantic movement. As Robert Alter wrote in his 1973 Commentary piece, Zionism descended from the Romantic literature and philosophy popular in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe. Alter credited Hebrew poets like Lamdan and Shaul Tchernichovsky with producing a “usable past” for early Zionists by combining Romantic literary techniques with Biblical themes. But Alter also observed that poetry and its attendant modes of thought tended to “pursue the possibilities of present things to the limits of their most extreme realization.” For this reason, he feared that Israel could become trapped in the fantasies out of which it was born — among them, that of a morally sublime suicidal martyrdom.

Of course, Israel’s sense of its own victimhood arose not only from deep historical and cultural roots but also from the unique conditions of its establishment: though some state called Israel might have existed without the Holocaust, it would not have been this Israel. As the historian Idith Zertal observed, paraphrasing an essay by Hugh Trevor-Roper in her book Israel’s Holocaust and the Politics of Nationhood, Israel extracted its “meaning and justification from the Nazis’ evil” and “construed the Holocaust into the great, teleological process of Israeli redemption.” David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, referred to Israeli citizens as “the redeemers of the blood of six million Jews.”

Even today, Israelis are addressed by propaganda both as permanent victims of gentile tyranny and as mighty Lions of Judah whose rights rest on their ability to claim with force the land they consider their birthright. Herein lies the emotional contradiction that animates Israeli politics: Zionism initially drew its energies from the effort to overcome the persistent existential dread experienced in the Diaspora, but in order to sustain itself, it has had to regenerate that dread continually. In other words, only Zionism’s failure can prove its necessity. Perhaps more importantly, self-destruction as a political collective permanently delays the traumatic moment at which Israeli society will be confronted by the crimes which made its development possible: the successive waves of ethnic cleansing perpetrated by the IDF and its precursors since the beginning of the Zionist project. To die together is to be spared the disintegration of constitutive Zionist fictions and to enjoy the return, from humdrum history, into myth. Meanwhile, the lingering future of collapse legitimates every obscenity and crime committed to prolong the state’s survival. In 1973, the Israeli historian Benjamin Kedar warned that the siege mentality of Masada could “pervert moral criteria.” As Kedar understood, the Israeli belief in perpetual, external threat was not only a source of anxiety and uncertainty, but also gave the “threatened” the right to commit any imaginable outrage against a perceived aggressor — a logic we see extended to its full, murderous dimensions in Gaza.

Israeli politicians frequently and cynically use the history of Jewish persecution as ongoing justification for Israeli crimes against Palestinians. Take, for example, Israeli U.N. delegates’ stunt in October 2023, when they wore yellow Stars of David, like the ones Nazis forced Jews to wear, to a meeting about Israel’s aggression in Gaza. More fancifully, in September 2025, Benjamin Netanyahu’s office responded to criticism from the Spanish government by raising the issue of its country’s crimes in the fifteenth-century Inquisition. (Benzion Netanyahu, Benjamin’s father, was a historian of the Inquisition. Contrary to the scholarly consensus in his time, he believed that Nazi-style racial antisemitism had its origin in the medieval Iberian construct of limpieza de sangre, or “purity of blood.”)

This approach, in which the Holocaust and other historical persecutions of Jews are made the analogues for every political gesture counter to Israel’s interests, can sometimes become so vulgarly literal that it takes on the tones of Holocaust revisionism. In a speech to the World Zionist Congress in 2015, for example, Netanyahu went so far as to pin direct responsibility for the Nazi genocide on the Mandate-era Palestinian nationalist Haj Amin al-Husseini. Netanyahu claimed that the idea to exterminate Europe’s Jews was not Hitler’s, but Husseini’s — intended to reduce the stock of potential Zionists. The Germans condemned Netanyahu’s remarks, observing, correctly, that they amounted to a minimization of Nazism. It’s easy to dismiss this kind of Israeli rhetoric, especially given the attitude the state took toward Holocaust survivors in its early years. (Ideological Zionists who had come to Palestine before the war called the Jews who had survived the death camps sabonim — a Hebrew pun on the words for cowardice and soap.) But Israeli histrionics, and the politics they are designed to defend, also reflect genuine belief in the impossibility of secure Jewish communal life, in the inevitability of murderous antisemitism, and in the untrustworthiness of any non-Jewish interlocutors in the struggle against said antisemitism. At the same time, claims like Netanyahu’s reflect a longing for the moral certainty afforded by extreme conditions of peril. When everybody’s out to kill you, introspection is, at best, distracting.

Israel must be both victim and victimizer; otherwise, Zionism’s delicate logic will collapse. For such a nation, convinced both that it is permanently and necessarily besieged and that it is the only possibility of survival for the people destroyed in the Holocaust; convinced both that it must live by its strength and that its strength is justified by the moral authority it derives from its weakness; convinced both that it has an unimpeachable right to exist and that it is the most fragile and vulnerable of existing societies, there is only one possible future — destruction — and only one way of redeeming that destruction — enthusiastic participation. Volunteering for the pyre. “It is life that is a calamity to men,” Josephus has the leader of the Sicarii intone, “and not death.” Israel’s fate, both feared and desired, is self-annihilation. The present massacre of Gaza’s Palestinians may come to a halt, but ethnic cleansing in the West Bank proceeds apace, and the Israeli government, to all appearances, remains unchastened. The long, bloody war between Israel and the many peoples of the Levant seems certain to continue, with a single imaginable end: the very end Israelis have never ceased imagining for themselves, an end toward which they orient their state ever more precisely with each new, staggering crime.

Yoni Gelernter is a writer living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Baffler, Santa Monica Review, Mississippi Review, Ninth Letter, and other publications.