Image by John Kazior

Image by John Kazior

Deep down, here’s what we already know: this is not just a war. It is not just a war because wars happen between states. It is not just a war because there is a world of difference between a military with the capacity to even consider cutting off water, electricity, and routes of escape to more than two million of its captives — and the people who are those captives. It is not just a war because if you are a Palestinian in Gaza today, you have two choices: stay home and die, or run, though you risk being bombed on your way out. (If you do make it to Egypt, good luck being allowed to come back home.) Not just a war because, as hospitals and churches in Gaza continue to get bombarded, Israeli-Americans are booking flights back to Tel Aviv to join the war; or return flights to New York to escape it. Return flight? Neither of those words are possible if you are a Palestinian in Gaza today. Carpet bombing an imprisoned population in the hopes that they will flee isn’t just a war. It’s something else.

Most of all, we know that this is not only a war because none of the liberties Israel is taking in Gaza now are powers that it has not also exerted on Palestinians in times of “peace.” Take the West Bank today — where, as the Egyptian comedian Bassem Youssef pointed out in a viral interview with Piers Morgan the night that upwards of 400 Palestinians in Gaza were killed at al-Ahli Hospital, there was “no music festival, no paragliding, no Hamas.” Nevertheless: not long after the October 7 massacre, most of the West Bank’s checkpoints were shut down.

“For security,” we nod knowingly. Yes — for security, the Israeli government then supplied West Bank settlers with automatic rifles. Yes, for security, it demolished a mosque in the Jenin Refugee Camp. The moment I learned about the checkpoints’ closing, I called my friend (he asked me to refer to him here as Khaled), who lives with his family in Ramallah. Khaled is like a brother to me; we spent four years studying Hebrew together as undergraduates. I pleaded with him — though I already knew the answer — is there any way for you to come to New York, to stay with my family, because in this real-life revenge fantasy of Israel’s, who knows what will happen to Palestinians in the West Bank. He said — though he knew I knew the answer — no, I can’t, there’s no way out now. He said, if I sing in Hebrew maybe it will confuse the settlers long enough to save my life.

I should have also checked on Khaled this summer. The horrific mass murder Hamas committed on October 7 was not the first major act of violence between the river and the sea this year. Just months earlier, thousands of Palestinians were compelled to flee the Jenin refugee camp when soldiers damaged 900 homes, part of Israel’s broader plan to “Break the Wave” of Palestinian resistance while building thousands more homes in illegal settlements in the West Bank. “We have to settle the land of Israel and at the same time, we need to launch a military campaign, blow up buildings, kill terrorists,” Israeli National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, himself a settler, said on a visit to the illegal settlement Evyatar in late June. “Not one, or two, but dozens, hundreds, or if needed, thousands.” Around the same time, Tally Gotliv, a member of the ruling Likud party, scribbled on Twitter: “Anisha kolektivit. Rak kach!” (Collective punishment. It’s the only way!). This summer’s furor came halfway through the deadliest year on record for Palestinian children in the West Bank. Several months earlier, the commander of the IDF’s Judea and Samaria division — which does little to stop attacks carried out by Jewish civilians — had deemed similar settler attacks in Huwara pogroms. Meanwhile, from his perch in Doha, Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh put out a message of solidarity that warned: “The blood spilled in Jenin will determine the next stage, on all potential paths. Our people and their resistance are able to respond to this barbaric aggression.”

A cycle of violence, we knowingly sigh. “This is what happens,” David Brooks wrote in a recent New York Times column, “when the center does not hold.” Witnessing recent events, we can be forgiven for seeing it this way: a story of extremists on both sides stymieing the well-intentioned efforts of reasonable folks in the middle, “leading to the bloodshed we see today,” per Brooks. And where does holding the center get us? After our hearts go out to Palestinians, after we mourn all lives lost, after we wring our hands over violence on both sides and call our representatives to demand ceasefire, now! and pray for peace in this war-torn region and denounce Islamophobia and anti-Semitism in all their forms — after all the hospitals have been flattened, all the blame deflected, all the posts re-posted; after all the Israeli ministers have resigned (or haven’t), it will only be a matter of time before the common-sense liberal asks: what now? In response to Bassem’s comment about state-sanctioned settler violence in the West Bank, Piers assured him, “I have made no secret that I think the conditions Palestinians have had to live under are completely unacceptable.” But, he went on, “the question then becomes, how do you forge peace between two warring parts of that region who for decades have approached peace with mutual sledgehammers?” But, we nod as Piers asks, “Where is the Nelson Mandela figure in all this?”

Palestinians, the pundits say, have never been an equal partner for peace. Our minds “flash back” — per David Brooks — to July 2000, when U.S. President Bill Clinton invited head of the Palestinian Authority Yasser Arafat and Israeli Labor Party leader Ehud Barak — who had just defeated Benjamin Netanyahu to become Prime Minister — to Camp David to arrive at a lasting peace. Betraying his own promise to Arafat that he wouldn’t point fingers if negotiations failed, Clinton helped reinforce the myth, further solidified during the outbreak of the Second Intifada that September, that the Israelis had made an unprecedentedly “generous offer” (as it was described across American media), only for Arafat to reject it and escort in its stead a violent uprising just when the two parties were on the verge of reaching peace. The summit became, in the American imagination, the most enduring symbol of Palestinian recalcitrance: “It is hard to see this kind of option ever being on the table again,” Brooks writes, “And the Palestinians let it slip away.”

But what, exactly, did the Palestinians let slip away? As a former British Foreign Office advisor observed in The Guardian two years later, “even the most cursory glance at the map revealed the bad faith inherent in it.” Sure, Barak offered Palestinians up to 96 percent of the West Bank (the exact figure remains debated). That is, he offered up to 96 percent of Israel’s definition of the West Bank — which deliberately did not include parts of the West Bank that it had recently seized. What the generous offer entailed, in practice, was Israel’s annexation of land — much of it fertile and sitting on top of water aquifers. The only territory that Israel would have returned to Palestinians in this deal consisted of desert land by the Gaza Strip that had been used for toxic waste disposal. Barak’s map showed the West Bank carved up and surrounded by Israeli troops and settlements, which would have made it impossible for Palestinians to travel or trade without the permission of the Israeli state. Above all, Israel refused Arafat’s request to cede “overriding authority” over airspace and water access. Another diplomatic expert at The Guardian reported that “the Palestine that would have emerged from such a settlement would not have been viable. It would have been in about half-a-dozen chunks, with huge Jewish settlements in between — a Middle East Bantustan.”

Sound familiar? Even Shlomo Ben-Ami, a former Minister of Foreign Affairs present at the negotiations, later admitted, “if I were a Palestinian I would have rejected Camp David, as well.” The “generous offer” proposed by Barak in 2000 — the alternate reality used as proof positive that, in former Foreign Minister Abba Eban’s oft-misquoted formulation, “Arabs never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity” — reflected the arrested status quo. Who, in this reality, gets to move? Even in times of so-called peace, Palestinians are paralyzed, in more ways than one. It’s not just that they cannot travel between the West Bank and Gaza, but that Palestinian movement within the West Bank is itself hampered by more than 500 perpetual, Israeli-controlled obstacles (primarily checkpoints and gates) as well as additional periodic closures to the entrance of Palestinian villages that can last for weeks. The mass arrests that escalated in the West Bank after October 7 likewise only reflect a broader norm in which Israeli forces make arrests with abandon: as of August 2023, over 1,200 Palestinians were administrative detainees — a full quarter of all the Palestinians incarcerated by the Israeli state. They are being held for unclear reasons, without stated charges, and without the opportunity for trial. (In a broader sense, too, Palestinians cannot move: an alarming percentage of them live below the poverty line, with no prospects for upward mobility.) Whether in the West Bank or Gaza, what we’ve witnessed after October 7 is different only in degree, not kind, from business as usual. As legal scholar Noura Erakat articulated in a 2014 interview during the assault on Gaza known as Operation Protective Edge, “It becomes about a ‘cycle of violence,’ despite the fact that Israeli military and settler attacks on Palestinians aren’t cyclical at all but constant. What we witness during specific periods of escalation is just an intensification of such attacks.”

Indeed, if this is not really a war, neither, according to Israel, is it really an occupation. Hence why, in what Erakat has deftly called a “legal sleight-of-hand” deployed by Israel since the 1967 war, the territories in the West Bank and Gaza Strip are neither occupied nor not occupied: while Israel undeniably maintains military control over them, it has rejected the legal obligations of Occupation Law that such control would normally entail. In plain terms, this means that the occupation could be indefinite as long as it is not explicitly permanent, a way to secure the continued seizure of Palestinian land — and expansion of the settlement enterprise — with utter impunity.

Amid the normalized brutality of this never-ending enterprise, pointing the finger at Palestinians for arresting the peace process is not just grotesque on a moral basis. It betrays a misunderstanding of the situation before us. Before and after Camp David, the meaningful return of land to Palestinians has been a non-starter for Israel. This is the reality check that Thomas Friedman offered us in his 1989 memoir From Beirut to Jerusalem, which offers a surprisingly clear-eyed assessment of the Israeli settlement project during the Lebanese Civil War and First Intifada. This was not 1947, when Palestinians believed they could hold on to Palestine, he wrote. “Now the tables are turned: the Israelis control all the land, and the Palestinians are seeking partition, and now it’s the Israelis’ turn to ignore the Palestinians for as long as they can.” If a state of coexistence is what we’re after, then it’s Israel’s leaders, not the Palestinians, who have repeatedly been unwilling to come to the table.

More than any other factor, Israel’s unwillingness to return land explains why the Gaza Strip exists in its current form. The official story is that Israel left Gaza in 2005 as a major concession to the Palestinians. And what did it get in return? Hamas fired rockets — resounding proof that concessions to Palestinians threaten Israeli security. But while Israel withdrew from Gaza with one hand, it accelerated the construction of West Bank settlements with the other. On the eve of the withdrawal, Dov Weissglas, then a senior advisor to Ariel Sharon, explained Israel’s thinking this way: “the significance of the disengagement plan is the freezing of the peace process.” As West Bank settlements multiplied, moral outrage could be directed at Hamas, whose takeover of Gaza in 2007 prompted Israel’s “temporary”-turned-infinite blockade.

And what of Hamas itself? In the early eighties, according to Yitzhak Segev, then Israeli military governor of Gaza, “The Israeli government gave me a budget, and the military government gives to the mosques.” The hope was to finance Islamic charities in Gaza that had been providing social services for its many poor as a kind of “counterweight” to the socialist Palestine Liberation Organization. Doing so, it was thought, would fracture a unified Palestinian movement, thereby enabling the further expansion of settlements. One of the Islamic charities receiving Israeli support was led by a charismatic imam by the name of Ahmed Yassin — the eventual founder of Hamas. Avner Cohen, a former Israeli official who worked in religious affairs in Gaza for over twenty years, confessed to the Wall Street Journal in 2009, “Hamas, to my great regret, is Israel’s creation.”

None of this should be a revelation. So why — despite the sober statements of genocide scholars and the dire warnings of United Nations experts; despite the mounting accounts from Israeli human rights organizations, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International; despite the careful citations from this Institute or that one — why, against all evidence to the contrary, does it seem so difficult for the American media establishment to affix the terms “ethnic cleansing,” “collective punishment,” and “crimes against humanity” to Israel’s actions? Why, despite this being, in one Israeli scholar’s estimation, a “textbook case of genocide,” are law firms rescinding job offers for students who say as much?

Here is what now-in-vogue terms like “settler colonialism” and “apartheid” fail to address, apt though they may be: the stubborn willingness, on the part of the Israeli state and its allies, to believe that there are no innocent civilians in Gaza, to insist that hospital victims are human shields, to argue, as the liberal Israeli MK Meirav Ben Ari did last Monday, that indeed “there is no symmetry” (ein simetriya) because “the children of Gaza brought it upon themselves” (ha-yeladim be-‘Aza hevi’u ‘al ‘etzmam et zeh) while “we are a peace-seeking people” (anachnu ‘am shocher shalom). This enduring belief that Israel acts only in self-defense is buttressed by a single premise: that Jewish lives must be valued over Palestinian ones in order to keep the former safe. If we hold this to be true, then the very existence of Palestinians is, by definition, a security threat. If we hold this to be true, then any opposition to such hierarchy is tantamount to anti-Semitism.

How did we become beholden to such a morally bankrupt paradigm? The sentiment, as voiced by American commentator Ben Shapiro, that “Israelis like to build” while “Arabs like to bomb crap and live in open sewage” is not just an outlying position of right-wing radicals; it is precisely what unified liberal American support for Zionist settlement in Palestine in the crucial years leading up to Israel’s formal establishment almost exactly a century ago. In April 1922, the Foreign Affairs Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives convened a hearing amid Arab protests in Palestine over the 1917 Balfour Declaration, which articulated British support for “a national home for the Jewish people” there. In his questioning of Selim Totah, a law student and native of Ramallah representing the Palestine National League, Representative Ambrose Kennedy remarked, “These Jews are making this land fertile where it was sterile.” To which Totah responded, “No, sir; I disagree with that in its entirety.” Kennedy persisted: these “have been lands that were sterile when they got them and they have turned them into fertile lands.” Totah insisted, “We could do that ourselves.” Yet throughout the hearing, the idea that Palestine was a “deserted country” where “the coming of the Jewish colonists commenced to change things for the better” prevailed. The Arabs opposing such migration, meanwhile, were “anti-Semitics,” “near-Turks” who, in the words of another Congressman present at the hearing, “object to the newer Western civilization which the colonist Jew is bringing to Palestine.” That June, the American Congress would endorse Balfour by voice vote.

The colonial nature of Zionism was best articulated by Theodor Herzl himself, who, in a 1902 letter, petitioned the notorious mining magnate Cecil Rhodes to support a project for Jewish settlement in Palestine. “You are being invited to help make history,” Herzl wrote. “It is not in your accustomed line; it doesn’t involve Africa, but a piece of Asia Minor, not Englishmen, but Jews.” He continued: “How, then, do I happen to turn to you, since this is an out-of-the-way matter for you? How indeed? Because it is something colonial.” Central to this endeavor, for Herzl, was the establishment of a “Jewish Company” that, like Rhodes’s British South Africa Company, would garner “immense profits.”

Contrary to both anti-Semitic and Zionist talking points, this colonial approach was far from the only, or even the most popular, vision for Jewish politics in the years preceding the establishment of the state of Israel. When I say this, I’m not just referring to the Jewish Labor Bund, the explicitly anti-Zionist workers’ coalition stretching from Vilna to Warsaw and beyond, and whose Polish wing dominated municipal elections even on the eve of the Nazi invasion in 1939. By claiming the lives of these Bundists, the leftist what-if goes, the gas chambers of the Holocaust incinerated an entire mode of Jewish collectivity directed at both combating anti-Semitism and participating in the struggles of other workers — a mode that we are desperately in need of today, yet one whose memory, due to its socialist presentation, was further disappeared during the Cold War.

Here is what critics and lionizers of Israel’s origins tend to elide when invoking the memory of the Holocaust: even in its immediate wake, mainstream American audiences, including Jewish institutions, did not see the establishment of a majority-Jewish national homeland as the obvious solution to the threat of anti-Semitism. And they did not need to resort to socialism to justify such skepticism. Widely expressed reservations about Zionism came from a far simpler source: as the late scholar of American culture Amy Kaplan recounts, “humanitarian sympathy often foundered on the political notion of a state based on an exclusive ethnoreligious identity.”

Indeed, as Bartley Crum, a civil rights attorney from San Francisco, remarked to Chaim Weizmann while serving as a member of a 1946 Anglo-American Committee assembled to collect Arab and Jewish perspectives on the question of Palestine, “We’ve had many difficulties with the words ‘Jewish state.’ Judge Joseph Hutcheson feels it suggests a narrow nationalism which he and, I think, many of us find abhorrent.” Weizmann nodded: “Yes, we are forever explaining that.” But, he continued, “Surely the world does not think that the Jewish people, who have suffered so much from narrow nationalism, would themselves succumb to it?” Notwithstanding Weizmann’s dodge, this Committee’s later-superseded final report rejected the establishment of a Jewish state, maintaining that “Jew shall not dominate Arab and Arab shall not dominate Jew in Palestine.” For his part, Lessing Rosenwald, then president of the American Council for Judaism, could not countenance “the Hitlerian concept of a Jewish state.” “In the immediate aftermath of World War II,” writes Kaplan, “‘narrow nationalism’ evoked the specter of parading brown shirts and fascist salutes.” The idea of a Jewish state nullifying an Arab majority offended the democratic sensibilities of most Americans, especially — not “even” — in a world recovering from the Holocaust.

So Israel’s ethnocratic state did not rise unchallenged from the ashes of the Holocaust: it had to be argued for. And in these arguments, it was assertions of Jewish supremacy, not concern for Jewish welfare, that ultimately justified the colonial project of settling an already-populated land. Nowhere were such arguments more vigorously pursued than in the offices of American liberalism’s most cherished left-leaning publications — think The Nation and The New Republic, not The New York Times or even Commentary. Take Freda Kirchwey, head editor at The Nation. From the pages of The Nation to the halls of the U.N., Kirchwey, a secular intellectual from a Protestant family, promoted the argument that a Jewish homeland would vindicate the struggle against fascism and anti-Semitism because — even if Zionism was by definition undemocratic — Jews themselves embodied a democratic ethos: their very presence would bring “peace in the Middle East and a more democratic development in that whole area.”

Far from being democratic, the development that Kirchwey and her liberal colleagues envisioned explicitly hinged on racial hierarchy: the “hierarchical coexistence,” to use historian Liora Halperin’s term, of Jewish workers over Arab ones. Such hierarchy went beyond superficial observations of Jewish whiteness. (Though that, too, played a role: James McDonald, a colleague of Crum’s on the Anglo-American committee, upon visiting an Orthodox synagogue in Jerusalem remarked, “I would have sworn that most of them were of Irish, Scandinavian or Scotch stock, or at any rate of the ordinary mixture of the American middle west.”) Entangled in these hierarchies were new development plans guided by the idea that, with the help of New Deal-style public works, enterprising Jewish farmers could make the desert bloom. In turn, it was thought, the lessons learned from what Eleanor Roosevelt dubbed “the democratic socialism of the labor-Zionists” could vindicate progressive efforts to manage ecological crises at home following the devastation of the Dust Bowl.

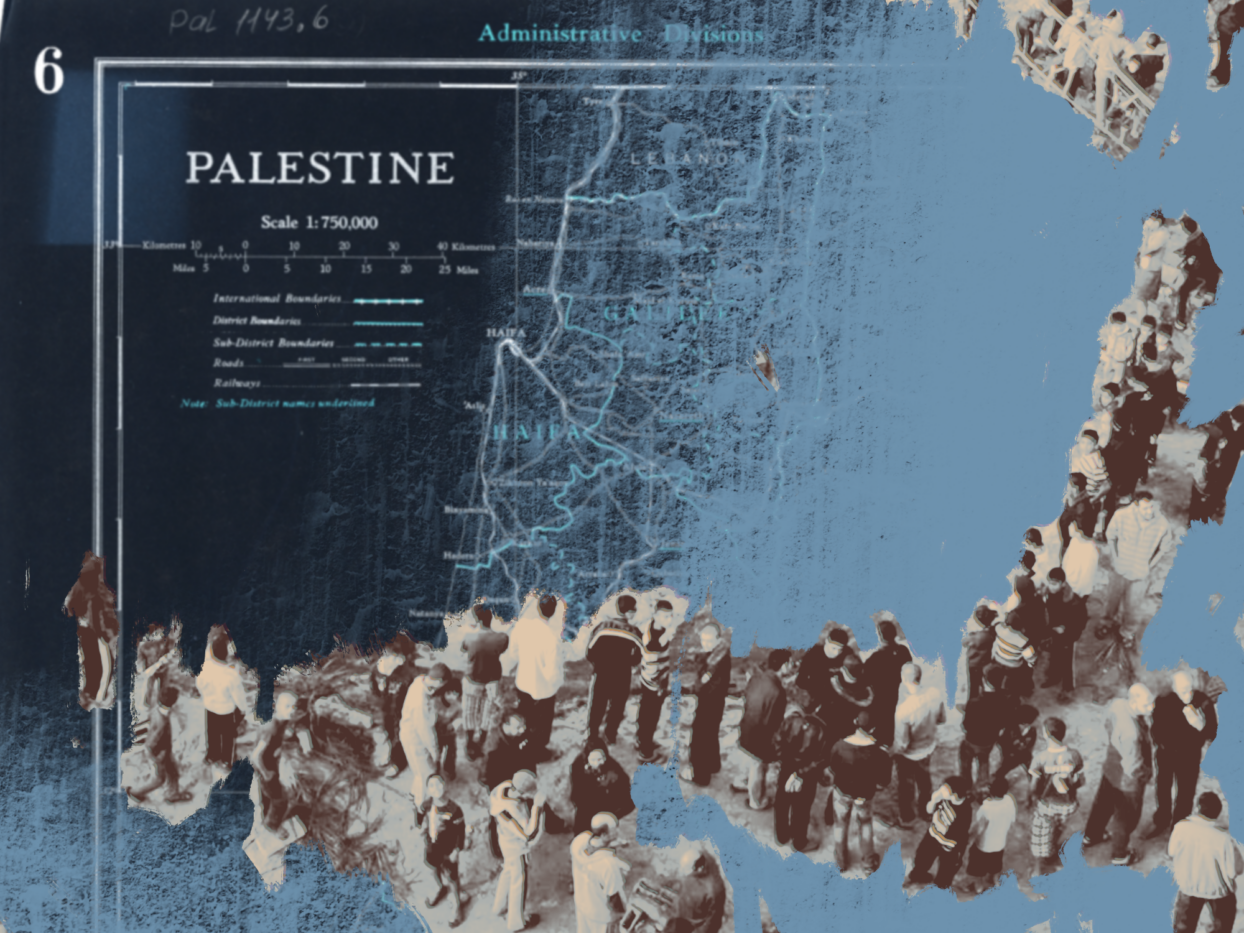

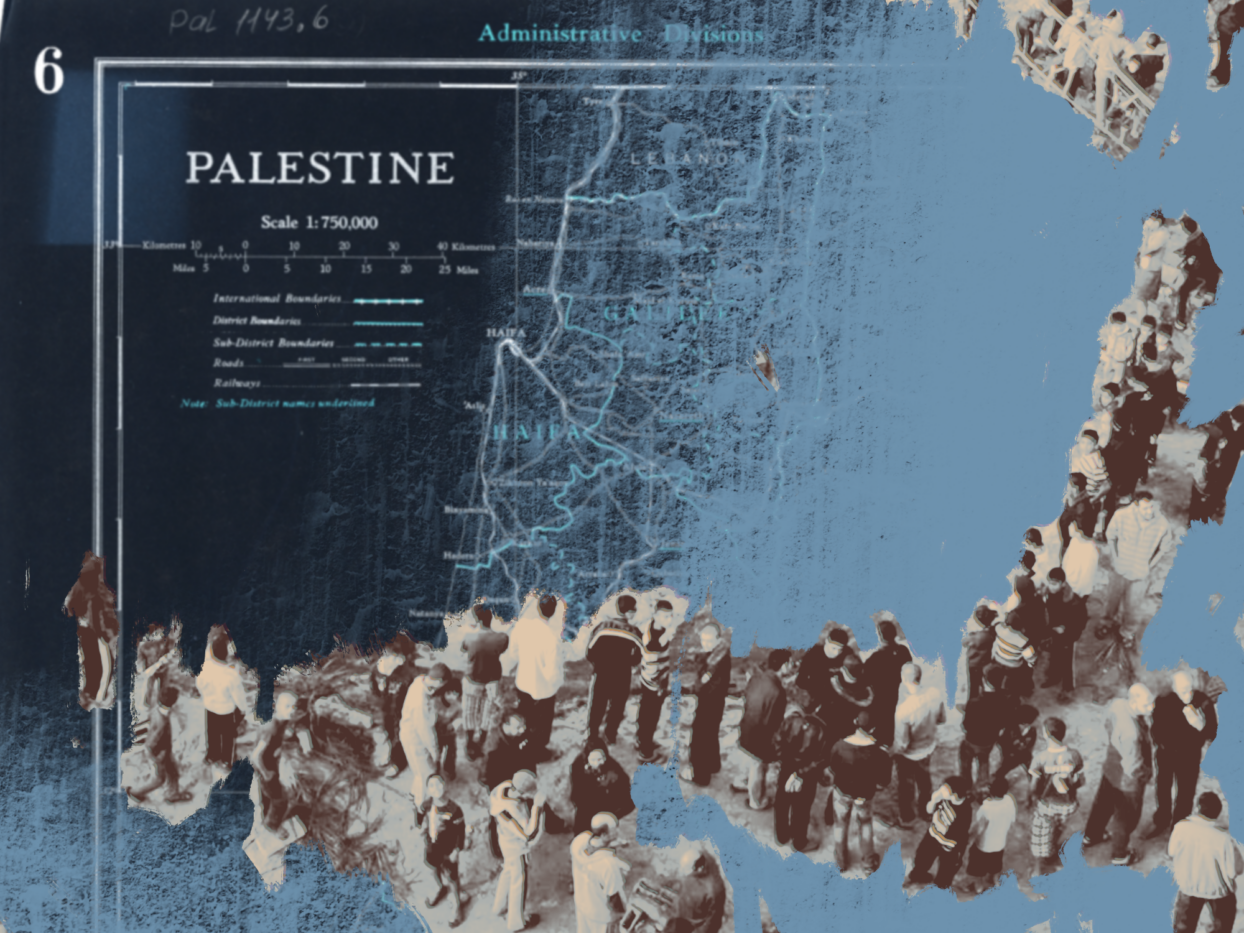

But there was one analogy, above all, that drummed up liberal American support for Jewish colonization in the leadup to the U.N.’s fateful adoption of the 1947 partition plan for Palestine: that between American and Jewish settler colonists. As agriculturalist Walter Clay Lowdermilk declared in his 1944 book Palestine: Land of Promise, which was published with the help of the American Zionist Emergency Council, “Colonization in America was like the colonization of Palestine.” That is, with one crucial difference: whereas American colonists in the New World were met with “new and bountiful land,” Jewish settlers would have to meet the “herculean task of reclaiming the long-neglected Holy Land,” a land whose decline began “with the first Arab invasion” of the seventh century. “Nowhere,” he insisted, “has the interrelation between the deterioration of a land and the degradation of its people been so clear as in Palestine.” Analogies between Palestine and the American wilderness allowed liberals to recast Zionists as resistors, not practitioners, of empire: in a 1947 article, Henry Wallace, the head editor of The New Republic, wrote, “Just as the British stirred up the Iroquois to fight the colonists, so today they are stirring up the Arabs.” What would become of these Arabs? In 1951, Kirchwey assembled nineteen “religious, labor, education, and liberal leaders” to co-sign a memorandum to the U.N. calling for the “permanent resettlement of the Arab-refugee population in the Arab States” — a plan, in other words, for ethnic cleansing.

Today, the justificatory tale of Zionism — that Jewish supremacy is necessary because it keeps Jews safe — can no longer hold water. I could say: because it endangers even Jewish lives. I could tell you that, after the joyous holiday of Simchat Torah, I turned on my phone to learn that my Israeli friend had been murdered in the largest massacre of Jews since the Holocaust. I could reveal that this friend was Hayim Katsman, a recent PhD from the University of Washington who spent his adult life writing about religious Zionism and working against the Occupation. I could tell you about how we walked around Lake Washington when I first visited Seattle in 2019, trading stories about the risks and obligations, as scholars of Jewish Studies, of naming settler colonialism. I could divulge that Hayim and I were research assistants for Liora Halperin, the historian who first applied the term “hierarchical coexistence” to Israel, that Halperin’s private endowment funding was once pulled after she signed a statement condemning Israeli state violence against Palestinians and supporting colleagues “working towards a process of structural change that would bring equality and justice in Israel/Palestine, a systemically unequal space that, nonetheless and inescapably, has a common history and future.” I could even share a video of Hayim’s sibling, Noi, pleading on television: “Most important for me and I think also for my brother is that his death won’t be used to kill innocent people.” Of Noi saying, “They always tell us if we’re gonna kill enough Palestinians, it’s gonna be better for us. But of course it never brings us peace, and it never brings us better lives; it just brings more and more terror, and more and more people killed like my brother.” Saying, “That’s not the way to bring peace and security to people in Israel.” Here is where I’d end by saying that the imperative to stand with Israel is a far cry from the values for which I converted to Judaism, a tradition that reveres machloket l’shem shamayim, disagreement for the sake of heaven. A tradition that repeats, “do not oppress the stranger, for you were once strangers in the land of Egypt.” I could say all of this. And it would all be sincere.

But that’s not how I will conclude. Are we so numbed to Muslim death — is the lingering smoke of post-9/11 racism so thick — that a 75-year campaign of ethnic cleansing, the longest of its kind, could not speak for itself? That we needed its Jewish casualties to finally help us recognize this kaleidoscopic catastrophe for what it is? In his interview with Bassem Youssef, Piers Morgan remarked that one thing, in all this, remains “inarguable”: “I feel that the scale of what Hamas did on October 7 supersedes anything else I’ve seen in this conflict, really ever.” As Palestinian casualties push 6,000 in the deadliest continuous assault on Gaza ever undertaken, is that so? As Israeli MKs call for a “Nakba that will overshadow the Nakba of ’48,” is that really so? Given all we know about the land theft, the displacement, the murder, the arbitrary arrests, the spatial and bodily crippling — the brutal occupation — of Palestinians since 1948, can that really be true?

On October 13, the Israeli military ordered a mass evacuation of one million Palestinians from northern Gaza to the south, ultimately directing them towards Egypt. It then bombed the humanitarian passageways leading there. Days after Israel’s ominous order to evacuate northern Gaza, which included 22 hospitals, Saleh al-Jafarawi — a survivor recording the bloodshed at al-Ahli Hospital — broadcast in Arabic to viewers on social media, “This is not yet another massacre [majzara]. Every time, we tell you ‘massacre.’ This is not a massacre. This is extermination [ibāda]. Extermination!” Behind his grief-stricken desperation is a political truism Weizmann dismissed, yet we must never forget: even a state built on the collective memory of ethnic cleansing and genocide is nevertheless capable of perpetrating them.

Who gets to resist Jewish supremacy? Certainly not Palestinians. What do those who decry violence have to say about the 2018 March of Return, when Israeli snipers shot at the legs and kneecaps of 40,000 peaceful Palestinian protesters in Gaza, killing 214, in an attempt to quite literally cripple their political movement? Never mind that Nelson Mandela founded the paramilitary wing of the ANC; if it’s a Palestinian Gandhi you’re after, look six feet under. (As Noura Erakat said in a recent media appearance, “This is about the right of Palestinians to resist at all.”)

Now, however, not even Jewish Israelis are spared. In response to a video in which he recited Kaddish for all victims of the war, including children in Gaza, the Orthodox-Jewish journalist Israel Frey was harassed by protestors after Shabbat last Saturday. Some of them threw flares at his home in Bnei Brak, intimidated him, even followed him to the hospital. In a video sent from hiding, he said that “Israel is in trauma,” but recent events “bring out what has been sown in us Israelis for years, only to grow stronger in this extreme and racist government: giz‘anut (racism), le’umanut (nationalism), and ‘eliyonut yehudit (Jewish supremacy).”

Last week, Israeli cabinet members proposed regulations to hunt any citizens deemed to be spreading information that “undermines the morale of Israel’s soldiers and residents in the face of the enemy.” Would our cherished “democracy in the Middle East” ever really implement such measures? It already has: as of October 18, more than a hundred Israeli citizens, many of them Palestinian, have been arrested for social media posts perceived to be sympathetic with Palestinians in Gaza. Perhaps only in this sense have we entered a state of war: not by Israel on Gaza (for no power they are exercising there is novel), or on Israel by Palestinians (for they have no state, and no real allies, with which to meaningfully wage one), but of Israel on its own citizens. The distinction now is not simply between who is an Israeli citizen and who isn’t, but between those who support occupation and those who — often by dint of simply existing as Palestinian — dare to resist it.

In a landscape where even peaceful resistance to occupation is met with brutal retaliation, Hamas opted to plan and carry out an evil, unspeakable act of violence. I do not condone it. Yet I also have the wherewithal to not condone it: I have not been living under siege for sixteen years. Instead, I am an American citizen. I can move practically anywhere I want, even in times of war: in the summer of 2014, I was tear-gassed by the Israeli military at a peaceful protest in Bil‘in on a Friday — and still managed to make it back to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in time for class that Monday. Palestinians, on the other hand, never escape conditions of war, even in times of peace: writes historian Seth Anziska about the gap year he spent studying in a yeshiva in Gush Etzion, an Israeli settlement in the West Bank, “Why were Palestinians unable to move freely, in the very same space where I, a U.S. citizen, could come and go as I pleased?”

Such is the privilege, and the responsibility, of being full-fledged citizens of empire: we are the only perfect witnesses of its crimes — the only ones who can look on with perfect immunity. Last Friday, Biden asked Congress to approve another $14 billion in funding for Israel’s war crimes. We finance Israel’s special relationship to the U.S., but it is others, ultimately, who have had to pay for it. Far from being “outsiders” to this carnage, you and I, dear reader, are its very conditions of possibility.

Days after the devastation at al-Ahli hospital, the U.S. used its veto power as a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council to quash a resolution calling for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza. And if it hadn’t? What kind of peace would we have returned to the morning after? We can make all the land acknowledgments we want, but for 75 years, our free and democratic countries have offered their utmost support to a state that violently enforces the supremacy of one people over another, at the cost of both. As long as we continue to enable these conditions, then it is we, not just Hamas, who have endangered human welfare. We, not just Israel, who have chosen ethnocracy over equality. We, not the Palestinians, who have been unwilling partners for peace.

How much more must we witness before we come to the table?

Nancy Ko is a writer, critic, and historian. She is based in New York and Rhodes, Greece.