Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

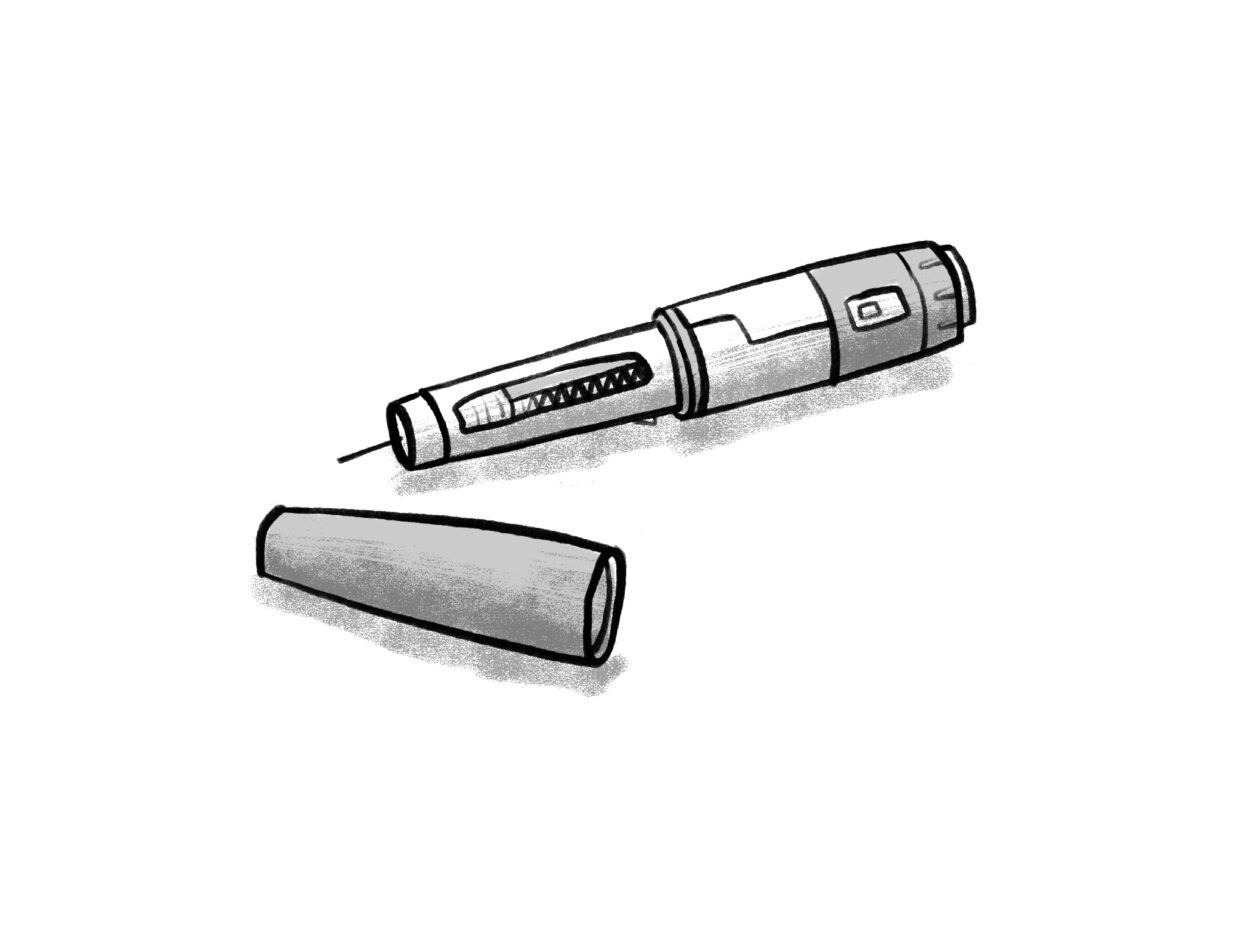

In a March 2024 special titled “Shame, Blame, and the Weight Loss Revolution,” Oprah Winfrey aired what was essentially an infomercial for a new class of drugs that promised to revolutionize the way we thought about obesity. The hour-long segment promoted Ozempic, Mounjaro, and Wegovy, which target GLP-1 (and, in Mounjaro’s case, GIP) receptors to make people feel fuller and slow the rate at which their stomachs empty. On the show, patients noted that the medications silenced their cravings for the first time. “It felt like I was freed,” one said. Winfrey agreed: “All these years, I thought all of the people who never had to diet were just using their willpower, and they were for some reason stronger than me,” she said. “And now I realize: y’all weren’t even thinking about the food! It’s not that you had the willpower; you weren’t obsessing about it!”

The new class of weight loss drugs has been accompanied by a reversal of much of the progress of the 2010s, when the body positivity movement promised to accept, and even celebrate, all types of bodies. Ad campaigns for companies like Dove and runway shows for brands like Fenty featured models of many sizes and shapes. But it’s now clear how empty the promise of body positivity was, and how persistent the cultural fixation on weight loss remains. Today, hunger and appetite are themselves pathologized; in the discourse surrounding medications like Ozempic, hunger becomes “food noise,” eating itself is rendered suspect, and fatness is reclassified as a disease that can — and therefore should — be corrected through pharmaceutical intervention.

The proliferation of GLP-1 forums, “what I eat in a day” videos, weight loss reveals, and new “skinny” influencers across social media illustrates this shift in real time. In “GLP-1 journey” posts, users describe side effects such as hair loss, fatigue, food preoccupation, and dry skin, and commenters cheer them on, recommending supplements and strategies to overcome weight loss plateaus. Meanwhile, celebrities Lizzo and Demi Lovato, once celebrated for rejecting diet culture, have visibly diminished; some, like Meghan Trainor and Serena Williams, publicly credit GLP-1 agonists (the drugs’ medical classification), while others remain conspicuously silent. Our feeds are filled with shrinking bodies, all repeating the same refrain: that they have never been healthier, happier, more well.

This doubling down on pharmaceutical weight loss as “wellness” exposes how profoundly our culture continues to misunderstand body size and appetite as levers under individual control rather than complex negotiations with our genetics and material environments, but American life today is often defined by the kind of precarity that forces bodies into survival mode: an increasingly unstable labor market; soaring rents; crushing education and medical debt; inaccessible healthcare; cities hostile to walking and public transportation; and food systems built on ultra-processed products engineered to be both addictive and nutritionally hollow. Under such conditions — what one physician, on a recent GLP-1-themed episode of “The Oprah Podcast,” clinically termed an “obesogenic environment” — it is no wonder that we struggle to nourish ourselves, oscillating between voraciousness and shame for feeling hungry at all.

Rather than attending to these structural factors, as Emmeline Clein and Jia Tolentino have both argued, we have developed a medically approved style of eating disorder. Between 2019 and 2022, eating disorder-related health visits increased by 41 percent, and, according to the CDC, emergency room visits for eating disorders doubled among teenage girls. In the same period, the newest iteration of appearance anxiety began to take hold: “Zoom dysmorphia,” so named by a Harvard Medical School professor who connected the fact that people were staring at their faces on screens for hours a day with an uptick in the prevalence of Botox, filler, and other cosmetic procedures. Wegovy was approved for weight loss in 2021, catalyzing the meteoric rise of GLP-1 pharmaceuticals. In May 2024, roughly one in eight U.S. adults reported having used them.

Dr. Elizabeth Wassenaar, a regional medical director at a national chain of eating disorder recovery centers, told me in an interview that she is already seeing patients come in with eating disorders that were reactivated by GLP-1 agonists. What’s more, the internet is rife with stories of people who have had to give up the drugs due to adverse side effects, loss of insurance coverage, or changes in financial circumstances, and — because most patients regain nearly all of the weight within a year of halting the injections — the results can be devastating. People who stop taking these medications “have these massive weight shifts,” Dr. Wassenaar noted. “I think we’re going to see a group of people who have also taken GLP-1 agonists who have long-term disordered eating.”

GLP-1 medications aren’t going anywhere; they’re too profitable. From 2020 to 2022, Novo Nordisk, the Danish pharmaceutical giant that manufactures Ozempic and Wegovy, nearly doubled its market capitalization, becoming responsible for the majority of Denmark’s economic growth. Ozempic and Wegovy sales generated $26 billion for Novo Nordisk last year, and the figure continues to climb. Analysts predict that the global market for GLP-1 medications will reach $105 billion by 2030. With an array of even more powerful drugs on the horizon, including oral forms, it’s hard not to imagine a sea change in the ways eating disorders manifest. Oprah’s so-called “weight loss revolution” has simply repackaged an old story — of hunger, willpower, and the fantasy of a body finally under control — and put it up for sale.

Vivian Hu is a writer from Texas.