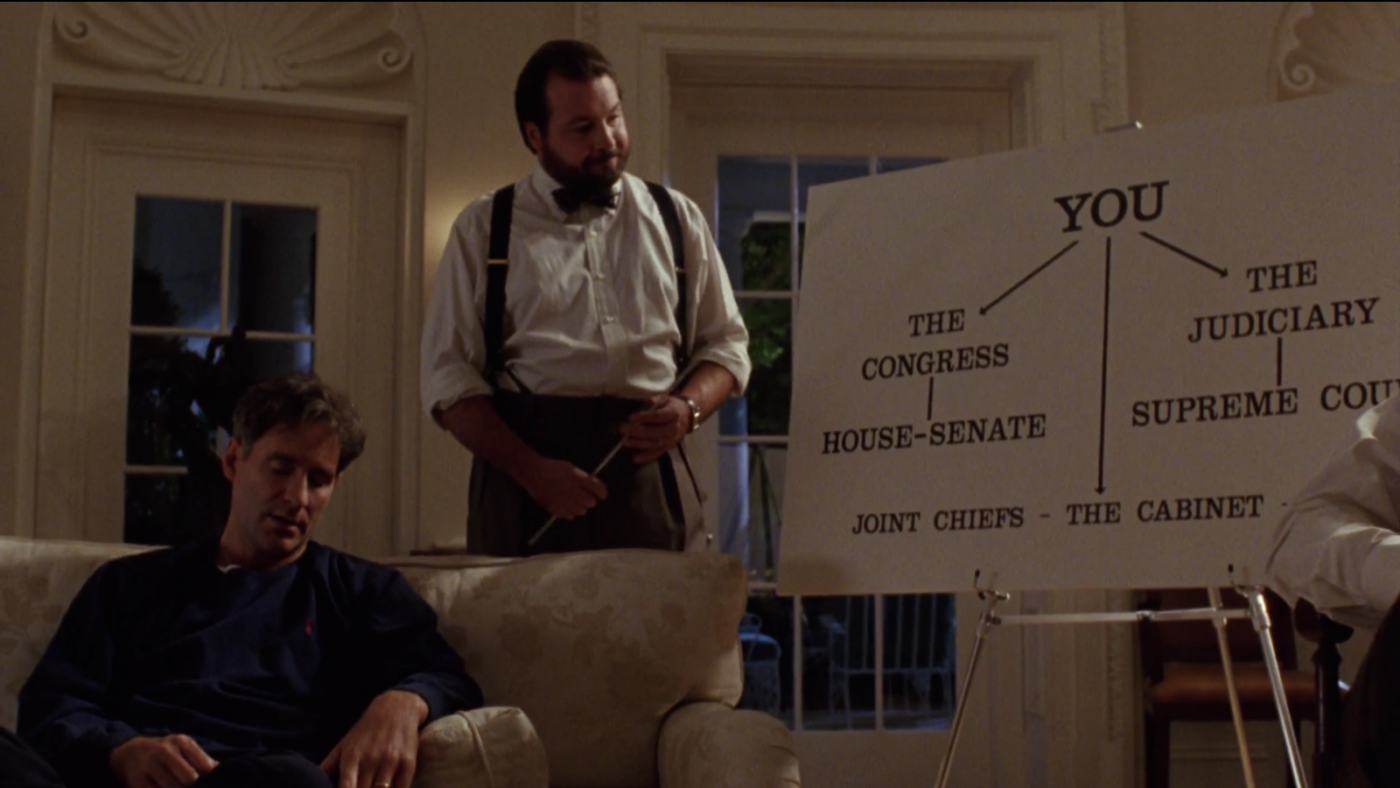

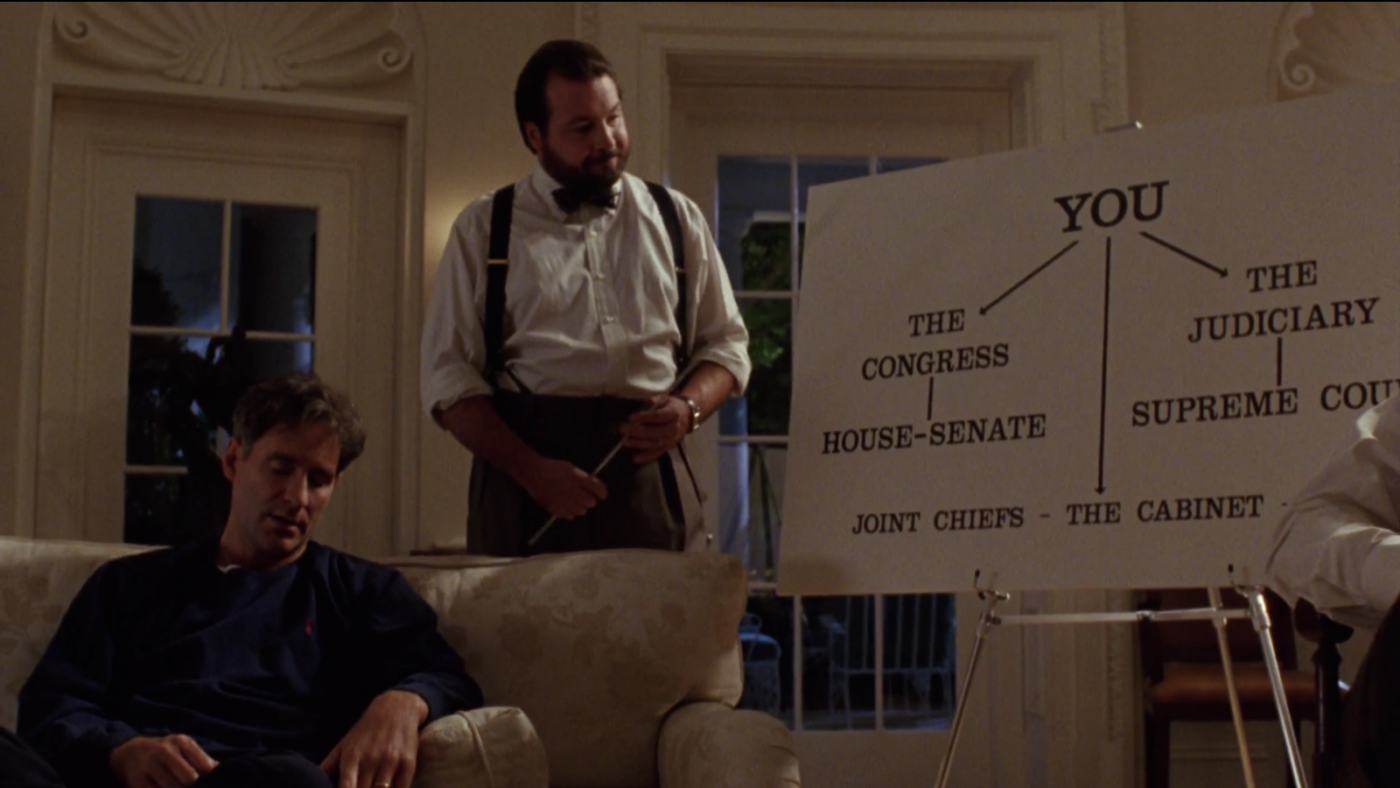

Kevin Kline learns civics in Dave (1993)

Kevin Kline learns civics in Dave (1993)

Surveying the canon of schlocky president movies will tell you there are two things a Hollywood audience loves: drama with the first daughter (kidnapped? new boyfriend?!), and an accidental president. The former can be explained away through our nostalgia for monarchy, or at least for princess tales; the latter by our democratic ideals.

The accidental president is a pipe dream — an unthreatening premise from which to launch a political critique. This is the fantasy: through some twist of fate, the president is swapped out for an absurdly unqualified everyman. Maybe the candidate is selected by the party for improbable reasons, or he (it’s nearly always ‘he’) decides to run and pulls off a surprise win, or else he finds himself almost magically transported into the Oval. Maybe there’s a plane crash or a heart attack to blame. However he’s installed in power, the newcomer has a good heart and a healthy ignorance of beltway politics, and some progressive policy victory is either promised or achieved — much to the chagrin of the politicos, who tend to end up with egg on their faces. But these films are driven by more than just schadenfreude; there’s also an earnestly proletarian moral, namely that an average Joe would make a better president than anyone poisoned by the DC establishment.

The genre dates back, arguably, to the Depression-era picture Gabriel Over the White House (1933). Produced by William Randolph Hearst, it stars Walter Huston as a corrupt, unfeeling president who gets into a car accident and, rather than dying on the spot, is transformed into a mouthpiece of the titular angel. With heaven pulling the strings, he declares martial law and browbeats the rest of the government into fixing everything from mass unemployment to racketeering, before achieving peace on earth and promptly suffering a fatal heart attack. The Nation called Gabriel an attempt to “convert innocent American movie audiences to a policy of fascist dictatorship,” but others saw it differently: The Hollywood Reporter predicted that the film “may put an end to the great problems that confront our nation today.”

Subsequent accidental president movies are comparatively uncontroversial. In Being There (1979), Peter Sellers is a middle-aged illiterate who lives in the house of a wealthy old man, tending the garden and watching television without ever setting foot outside. When his benefactor dies, Sellers finds himself ejected quite literally out of the garden and onto the mean streets of Washington, DC. He is capable of exactly two feats: mimicking whatever’s on TV and intoning basic gardening instructions. Due to his slow, measured affect, these botanical maxims are misinterpreted as economic metaphors and sage political advice. “In the garden, growth has its seasons: first comes spring and summer, but then we have fall and winter,” he says, earning a citation in the State of the Union. At the film’s conclusion, party hacks hold a hushed discussion about a potential substitute for the flailing president, and unanimously agree on the gardener. (Though he never has the opportunity to test out his governing chops, Sellers does walk on water in a memorable closing shot.)

A decade and a half later, Kevin Kline gets some Oval Office time in Dave (1993) as a part-time presidential impersonator recruited to stand in for the comatose commander-in-chief. Initially obedient, Dave soon learns that the real president, also Kevin Kline, is a schmuck — embroiled in fraud and cheating on First Lady Sigourney Weaver with secretary Laura Linney. Power-hungry West Wing staffers treat Dave as a pawn, but unfortunately for them, he has a conscience: using common sense and ordinary empathy, he outdoes his doppleganger, becoming a better president (universal jobs program, funding for the homeless, a balanced budget) and a better husband to Sigourney.

“There are no red states or blue states, only the United States” is often misremembered as the signature line of Barack Obama’s 2004 DNC speech. In fact, Obama said something subtler and wordier about Little League and worshipping an awesome God. He did use the line in 2008, but not before accidental president Robin Williams, who tosses it off in Man of the Year (2006). Possibly the worst of the bunch, the film features Williams as a late-night comedian whose joke campaign for the presidency turns serious when a glitch in the new digital voting system accidentally declares him the winner — a premise that might sound unbelievable, if an app hadn’t botched the caucus results this past year in Iowa, presenting Pete Buttigieg with an accidental victory and throwing a spanner in the works of the Bernie Sanders campaign. “There are no red states or blue states, only the United States,” Williams says in a big address intercut with scenes of tech company whistleblower and genre veteran Laura Linney evading kidnappers in a mall. (This movie is very very bad.)

An exhaustive taxonomy might list many more accidents. In Americathon (1979), after Jimmy Carter is lynched, the electorate picks out the unqualified Chet Roosevelt solely on the basis of his last name. Head of State (2003) tells the story of a DC alderman (Chris Rock) nominated to replace a dead presidential candidate in a craven party bid to turn out Black voters. Expected to act as dutiful patsy, Rock soon bucks his handlers, delivering barnburners on working class issues, releasing a rap video campaign ad, adopting the slogan “That Ain’t Right,” and ultimately winning the presidency. Swing Vote (2008) is about a typical, disengaged citizen who, due to a close election and an irregular ballot, is tasked with choosing the president and develops a sense of responsibility for the suffering of ordinary Americans. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939, feat. Jimmy Stewart), Bulworth (1998, Warren Beatty) and The Distinguished Gentleman (1992, Eddie Murphy) are congressional variations on the theme.

The palace intrigue is frequently goofy — filled with machinations and contrivances, gimmicks and misunderstandings — but it also spotlights a question mark at the heart of the American political identity. “Prince and the pauper” narratives, theoretically, should have no place in describing a representative government; the point of an electoral system, as opposed to a monarchy, is government by the people. What these movies tell you is that the audience-cum-electorate harbors no such delusions. The notion that only someone inexperienced could “drain the swamp” is baked into our national consciousness. You, too, could be a great president!

Sometimes, fantasy spills over into real life. In a Ukrainian spin on the plot, Servant of the People (2015-2018), a high school history teacher played by Volodymyr Zelensky is elected president after a classroom video of his curse-filled rant on the subject of government corruption goes viral. By 2019, the eponymous Servant of the People party had won a parliamentary majority, and Zelensky had quit comedy to serve as Ukraine’s actual president. (He now faces allegations of corruption and abuse of power.)

The case of Donald Trump is not quite as parodic. Trump never played a president on TV — only a generic rich guy, in comedies like Home Alone 2: Lost in New York (1992) and Two Weeks Notice (2002), before landing the role of a successful businessman in The Apprentice (2004-2017). But Trump, too, rose to power on the animus that motivates the accidental president genre: the dream of a rookie politician able to shake things up.

A joke right until the moment the New York Times’s election needle began its surprise rightward tilt, a Trump vote was a fuck-you to the establishment. The best-case scenario, for Trump supporters, was that their candidate might fix DC politics, because in the style of a Kevin Kline or Chris Rock, he wasn’t beholden to any of the hucksters in either party. The concomitant nightmare, for anyone left of Mussolini, was that Trump might succeed — that he might embody a Bannon-style populism, overhaul the Republican party, start jobs programs, and (amid an upswing of nativism and xenophobia and racism) make life easier for a white majority.

Four years later, it’s safe to say that hasn’t happened. And Trump has faced something that none of the accidental presidents do: a bona fide crisis. In the films, the day-to-day elements of overseeing a massive bureaucracy remain hazy. Presumably the staffers, despite their elitism and cronyism, have been around long enough to know how to coordinate with the CDC, but their administrative expertise is never put to the test. Since Trump, unlike the fictional executives, was able to pick his own advisors, we found ourselves relying on a ragtag team of as-yet-unfired family members and sycophants to round up PPE.

But the prospect that a President Joe Biden would be any less dependent on staff seems far-fetched. The movie most frequently cited to mock the Biden campaign is Weekend at Bernie’s (1989), a comedy in which two young employees prop up the corpse of their company’s CEO and pretend he’s alive. With his dead-eyed gaze and his bumbling debate answers, Biden would make, in his own way, for an accidental president. Unlike any of the fictional protagonists, of course, he’s been running his whole life. But even in middle age, Biden was hardly a paragon of political prowess. In 1988, he withdrew from the race after it was revealed that he had fabricated parts of his family history to better plagiarize a speech by Neil Kinnock of the British Labour Party. Nor was he a strong contender for the nomination in 2008. He came in fifth in Iowa and was only chosen for the vice presidential slot because he was white, male, experienced, and — per a contemporary New York Times article — considered too old to spend his term vying for a post-Obama presidency. The accident of Biden’s nomination is that it only happened this time around, with the candidate clearly past his prime. It took a perfect centrist storm — Pete Buttigieg’s unexpected Iowa victory, some progressive vote-splitting, and a coordinated mass exodus of moderates right before Super Tuesday — for him to eke out a win.

There’s something uncanny about the run-up to November: two accidents talking past each other in their respective town halls. No one expected the Trump-Biden debates to be Mensa-level meetings of the minds, but watch the candidates side by side, and you get the impression of accident versus accident — men in varying levels of cognitive decline whom different segments of the electorate have decided to pretend are up to the job, as if we could render either adequate by sheer willpower. This election season, in a reversal of the accidental president trope, we’re effectively choosing which set of staffers we’d rather have in charge during the Covid-19 crisis. A vote for Joe Biden is a vote that his staff will be better equipped at the managerial functions necessary to coordinate pandemic response than Trump’s. We can only hope that the behind-the-scenes hacks running Biden’s candidacy will stick around and continue to pull the strings of a Biden administration.

If the accidental president genre is our reality, some meaningful segment of the political-cultural elite is nostalgic for a different brand of political fantasy. On October 15, HBO aired the clunkily titled “West Wing Special To Benefit When We All Vote,” an hour-long production in support of Michelle Obama’s GOTV organization. The event was not a reunion, showrunner Aaron Sorkin insisted. Instead the cast recreated, line for line, a 2002 episode as a filmed stage play (a form favored only by Broadway superfans, and abjured by everyone else in the history of television reunions for a reason). In commercial breaks, Michelle Obama, Bill Clinton, Lin-Manuel Miranda, and Samuel L. Jackson, as well as original cast members, chime in on the importance of voting — apparently under the illusion that many non-voters are sufficiently gaga for The West Wing to tune in.

After fourteen years off the air, the long-running drama still has remarkable purchase on the national political imagination. As has been well documented, it was instrumental in shaping the worldview of a generation of politicians, aides, and commentators. Pete Buttigieg, who organized West Wing watch parties in college, told an interviewer that the show “created a certain view of what we hope the White House would be like, in terms of the intellect and in terms of the intentions of the people who are there.” Obama speechwriter David Litt has likewise written that he was “raised, in part, by Aaron Sorkin.” Other Obama advisors have spoken openly of being dismayed, post-inauguration, to find the HBO satire Veep (2012-2019) a better approximation of real-world politics. Campaign in Sorkinese, govern in farce.

The West Wing universe, indeed, is anything but accident-prone, and its president, Josiah Bartlet, was born for the job. On the show, politics is not a tangle of corruption and incompetence, but an arena of hardworking idealists, worthy institutions, and principled compromise in the name of patriotism. In “Hartsfield’s Landing,” the episode reenacted for the HBO special, Communications Director Toby Ziegler articulates the show’s ideology over a game of chess with Bartlet. The president, Toby thinks, is pulling his punches, afraid of being seen as obnoxious or over-intellectual. Toby tells him to cut the folksy act: “You’re not a regular guy. You’re not just folks. You’re not plainspoken. Do not, do not, do not act like it!” Instead of dumbing himself down to avoid a perception of snobbiness, Bartlet should play to his strengths. “Make this election about smart and not,” Toby says. “Make it about engaged and not, qualified and not.” It’s a pivotal scene, one that determines Bartlet’s aggressively erudite posture in the campaign that follows. And because The West Wing is fiction, the strategy works.

As has been pointed out in a slew of post-2016 takedowns of the show, qualifications, engagement, and intellect did not win Hillary Clinton the presidency. But decades before the episode was originally written, “smart and not” had already been attempted. In Reaganland, Rick Perlstein writes that the Carter campaign used nearly identical logic in its disastrous reelection bid, placing an all caps directive atop its media plan: “CARTER IS SMARTER THAN REAGAN.” Democratic strategists imagined this to be an unimpeachable argument, but Reagan characterized Carter as “mean,” and the charge stuck. Polled on whether a candidate had been “especially unfair,” 40 percent of the general public picked Carter, next to 23 percent for Reagan. In 1980 as in 2016, the electorate wasn’t interested in picking the smarter of two rivals.

And in 2020, smart and engaged are not on the menu — which is perhaps why Toby’s pep talk in the HBO special plays strangely as part of a plea to support Joe Biden. While he may share some critical mass of moderate-liberal West Wing policies, Biden is in every way the antithesis of a Bartlet. Joe Biden is a regular guy. Joe Biden is just folks. Joe Biden is, when he can rise to a certain level of coherence, plainspoken. Joe Biden may be just the accidental president America wants.

But accident or not, Biden has made clear that he won’t bring about any ruptures in the system. The accidental president who saves the day is as much a chimera as The West Wing’s vision of government by the best and brightest. Absolute democracy or meritocracy, the twin myths of our political life. And if The West Wing has overstayed its welcome in the collective consciousness, so too has the accidental president. The shtick makes for a fun movie premise because it lampoons the political sphere without seeming remotely plausible — Dave and Head of State are whimsical comedies, not realistic dramas. But it’s hard to find the joke charming, or the potential for transformative change credible, anymore. We’re unlikely to have more feel-good accidental president flicks, at least in the near future. Regardless of who wins in two weeks, the genre may have jumped the shark.

Rebecca Panovka is an editor at The Drift.