Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

Image by Ivy Sanders Schneider

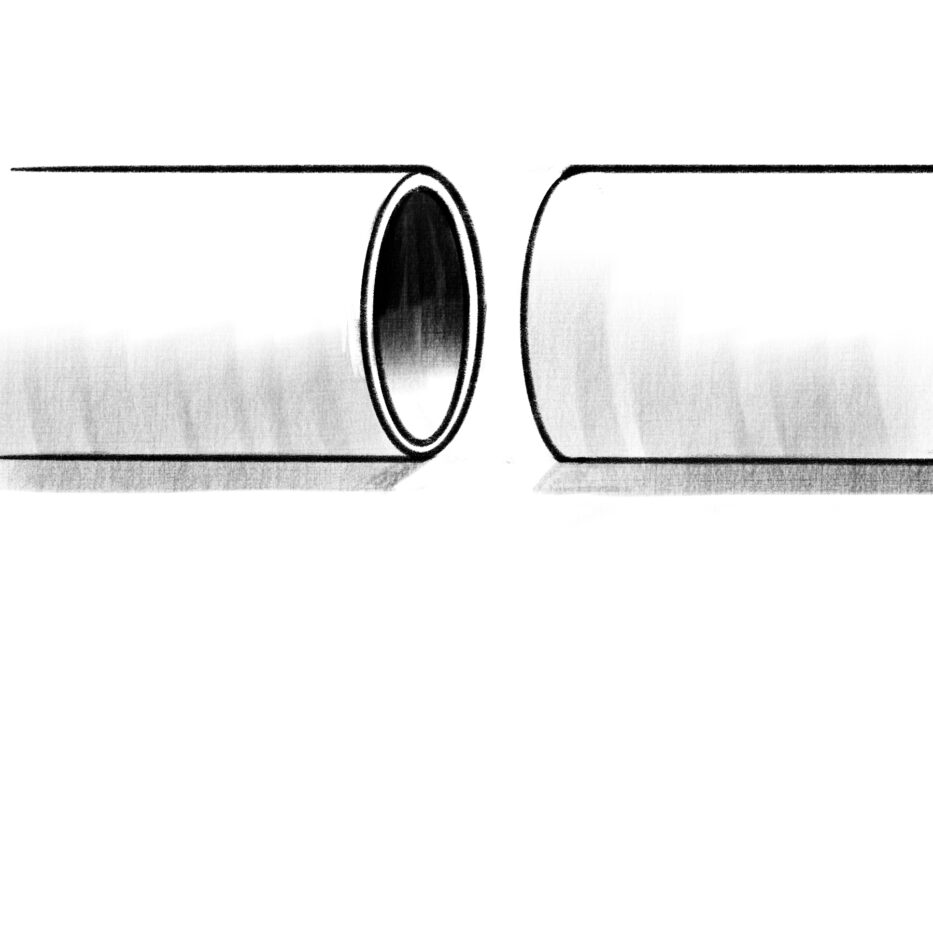

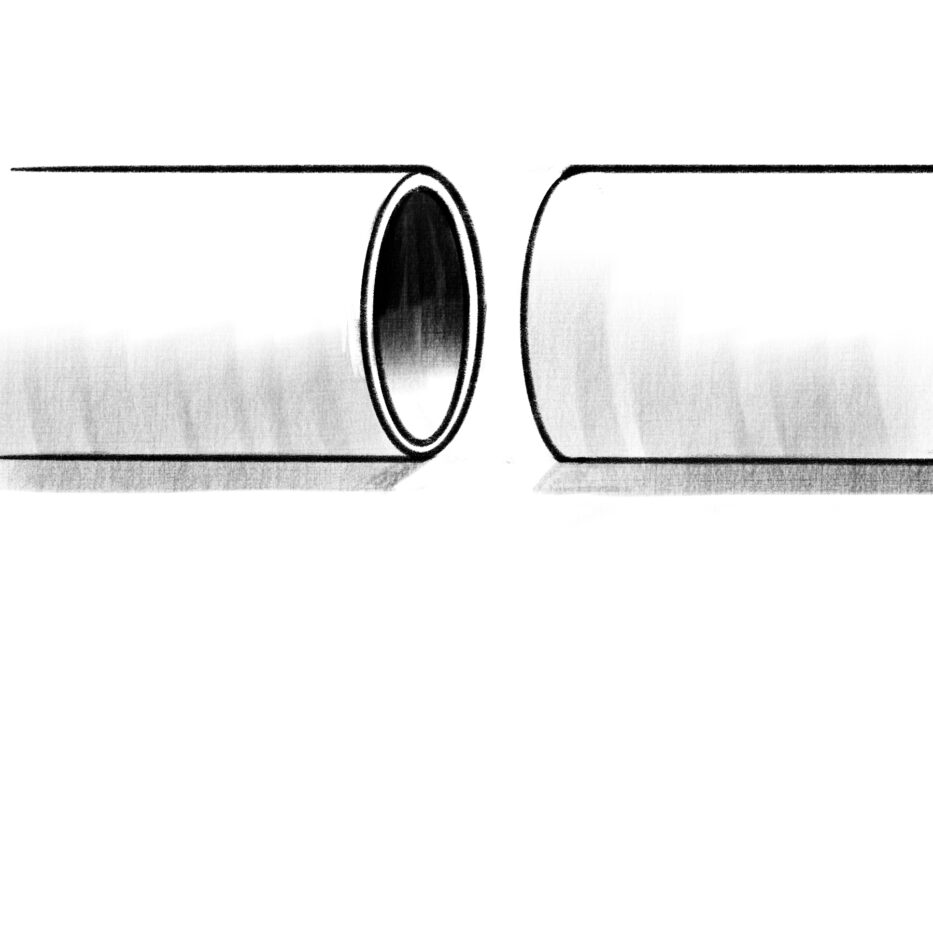

What else could have secured a “yea” vote on the Inflation Reduction Act from Senator Joe Manchin other than a juicy pot-sweetener? In addition to a promise to ease permitting restrictions for new fossil fuel infrastructure, Manchin won a pledge from Democratic leaders and the White House that they would “take all necessary actions” to “complete the Mountain Valley Pipeline,” a 300-mile fracked gas pipeline through poorer regions of West Virginia and Virginia that, if finished, would have a climate impact roughly equivalent to that of 26 coal plants. During this election cycle, the pipeline’s corporate stakeholders have been some of Manchin’s (and Majority Leader Chuck Schumer’s) biggest donors.

Resistance to the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) stretches back years. After construction finally began in 2018, local activists initiated a campaign of direct action, occupying trees and chaining themselves to construction equipment. The response from the state was severe: dozens of arrests, with several activists eventually charged with making threats of terrorism. “We’re dealing with an ecology of oppression and violent structures that are tied together and interwoven, structures that are opposed to human survival, freedom, autonomy, and the land,” one yelled from her arboreal perch. In 2019, Virginia’s anti-terror unit put out a report arguing that the Mountain Valley resisters were “co-opting” tactics from Al Qaeda and the Taliban, according to reporting from The Intercept’s Alleen Brown. But, at least for a while, the pipeline appeared to be on its last legs. “The writing for MVP is on the wall,” environmental activist Crystal “Red Bear” Cavalier-Keck, a member of the Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation, wrote in a February article in The Nation, after citizens’ groups won a series of court rulings. “It is time to abandon the project.” Manchin wasn’t deterred. A month later, he called on Joe Biden to invoke the Defense Production Act to finish the pipeline in order to boost U.S. natural gas exports to Europe. “I’ve been preaching to the heavens for a long time on this one,” he told the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

The last decade will be remembered as a moment of expanded and renewed climate justice activism. It will also be remembered as a period of steadily increasing coordination between extractive corporate interests and the repressive powers of the U.S. state. In 2017, hundreds of indigenous water protectors and other allies faced criminal charges related to protests in the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. During the brutal crackdown, local, state, and federal authorities coordinated closely with a private security firm founded during the Iraq War by retired members of the U.S. Delta Force. The firm labeled protesters “jihadists” in internal documents, and one of the activists it targeted received an eight-year prison sentence after prosecutors secured a terrorism enhancement. In the years following Standing Rock, seventeen states enacted steep penalties for protesting fossil fuel infrastructure in what climate movement attorney Ted Hamilton calls “climate law’s police phase.” Oklahoma’s version of these so-called “critical infrastructure laws” — like many others, a near-exact copy of model legislation produced by the Koch-backed American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) — made it a felony (punishable by a fine of up to $100,000, ten years in prison, or both) for anyone to damage, tamper with, or deface fossil fuel infrastructure. In Manchin’s West Virginia, merely conspiring with someone who trespasses onto a pipeline or storage facility could get you slapped with a several-thousand-dollar fine.

Just over a decade ago — long before “critical infrastructure laws” were even a gleam in an ALEC lobbyist’s eye — Timothy DeChristopher was sentenced to two years in federal prison for disrupting an oil and gas lease sale. While incarcerated, DeChristopher began to see that the movements to abolish prisons and fossil fuels were deeply connected. His time in prison, he later told a journalist, only made him “more of a revolutionary.”

Jack McCordick is a reporter-researcher at The New Republic.