Ronnie did not know the bed-and-breakfast was haunted until she checked in. Then, there it was, proudly announced on a leaflet propped up on the desk. The Fifth Most Haunted Building in the Country. They went all over, assured the woman retrieving Ronnie’s room key, and this place came in the top five!

The woman was proud, referred to the ghosts as “they.” Told Ronnie that they must have put on a real show that night, the night the judges came to stay. She winked, which made Ronnie wonder if the whole thing was a farce, until the woman began her description of the ghosts, a woman in gray — who frequently broke windows in the attic and, once, a glass salt shaker — and her supposed husband, also gray, who liked to lurk in corridors.

Now, the woman lifted her hands as she spoke, all the salt shakers are metal and there’s only one local builder left who’s brave enough to come back to do the repairs! Ronnie nodded. Did the woman want her empathy? It was hard to tell. They’re angry about something, the woman conspired, holding onto Ronnie’s key until her explanation was over, or at least she is, the wife, we reckon it’s her daughter, drowned right on the beach, can you imagine? Of course you’d come back, as parents, that’s what you do!

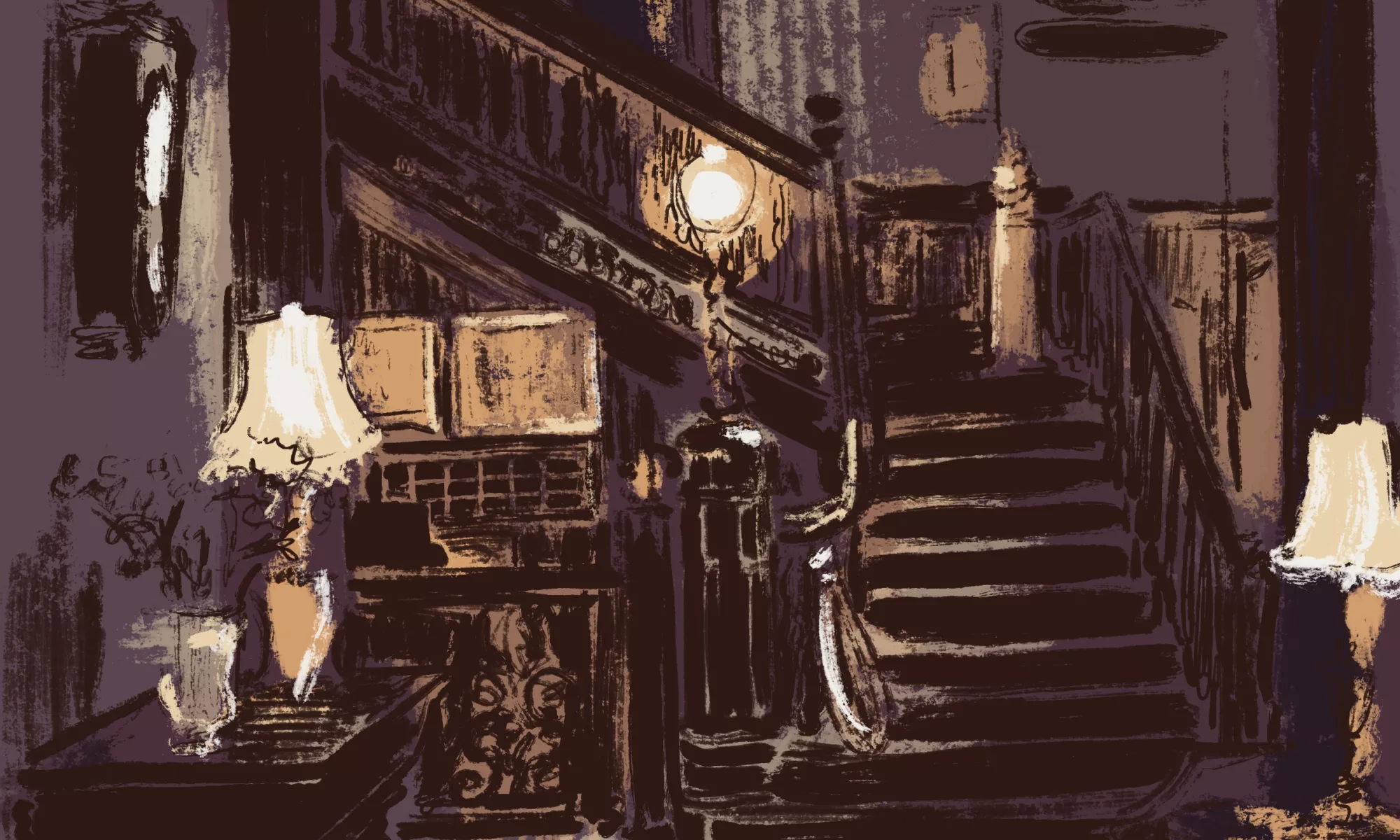

Ronnie disagreed. It was better to stay where you’d been left. Especially if you were a parent. She looked around the room more nervously than she would have liked. Don’t worry love, you won’t find her in here. The woman handed over the key, enormous and brass. The wife prefers it upstairs. Ronnie felt she had to ask: and the husband? The dining room, one of our guests saw him at the breakfast buffet once, it was very early mind. She winked again. This time Ronnie wondered if she was flirting.

Which reminds me, you can get your breakfast from 5 a.m., if you want company. No wink this time. The woman was talking about the gray husband. Ronnie pictured him, lanky and awkward in a suit, peering out at stale croissants. Finishes at 8:30 sharp, all the good bits go early and won’t be replaced, when it’s done it’s done. Spectacles hung around the woman’s neck. She polished them, her navy blouse pinched between finger and thumb. Not a problem, Ronnie added, I’m a morning person. Well that makes one of us. The woman smiled vaguely, as if being asked to pose for a photograph she did not want to be in.

Ronnie went to take the leaflet then decided against it. Carried her duffel bag up the narrow staircase. There were only ten rooms. She’d chosen the place because it was small. Each room offered a view of the sea, had an old bathtub balanced on clawed feet. She’d missed the part about the ghosts. Perhaps they did not directly advertise it. The status just for people in the know. She sat on the edge of the bed and waited, briefly, for something to happen. She believed in ghosts, but not in any dramatic way. The feeling was accidental, unprocessed. Inherited from somewhere, maybe her childhood. They’d gone to church, both her parents believed in heaven and hell. A ghost wasn’t much of a step.

Out the window the sea was molten blue. Gray funnels of cloud raised on the horizon, rain over the deep. She studied her reflection in the glass, double-checked the space above both shoulders. No husband, no wife. The room was cozy, on the verge of too warm. The window was painted shut. She fiddled with the heating controls. Drank a glass of water. Spring had been damp, she hoped for a break in the thick sky, she leaned to look left and right. The town was quaint. Buildings painted bright pastels, a charming stone harbor, fishing boats rocked on a departing tide. There was no sun, not even enough blue to patch a sailor’s trousers, a phrase that belonged to her mother. Seagulls settled and screamed on the connecting building. Ronnie unpacked. Placed a toothbrush on the sink and wondered if it would move, made a mental note of its exact position. Her stomach rose and fell. Other footsteps in the hallway made her jump, but the voices were human, a couple arguing softly about who had the room key.

Ronnie paused at her clothes. Without thinking she’d packed an old jumper, a favorite, pale green, the name of a hockey team across the front, from her days playing club. Spotted short white hairs caught in the fabric. She was aware of the space below her diaphragm, imagined it unzipped, hard black all the way down. When a dog died people were only sorry for an hour or so, the length of a coffee, a slice of carrot cake. She had not been able to move Davy’s ashes since. They remained in the tacky vase, the tacky card from the vet still sellotaped to the front, Our Condolences, a watercolor picture of a sheepdog and a tabby cat surrounded by pink hearts. She’d come home afterwards, panicked, and wedged him in between the Christmas booze, a sticky bottle of Baileys and an unopened Cointreau.

She stuffed the jumper back inside the duffel. The bedside alarm clock claimed 12 p.m. Grateful she could go out for lunch. At the front door Ronnie smiled at the woman behind the desk, who leapt into action, want me to recommend anywhere? Everything ok with the room? She also wore jewelry that jiggled, her necklace made up of ceramic shells, the polished spectacles, green plastic bangles around her left wrist. All good, just going to wander. Lovely, yes, have a lovely wander, you enjoy yourself!

It was shoulder season. The town bolted down. Ice cream shops shuttered, the small museum closed. Wind barrelled off the sea and into her side, flattening her jacket against her body, like she’d been cling-wrapped. She peered over the edge of the harbor. A great stink rose from the exposed sand and sludge, seaweed stacked against the walls. She followed a path through the houses, angling up, until there was a view of the coast, the next three villages over. It was bearably beautiful. Purple light, veins of wash.

There was one pub open. A proper fire, a promise the building was at least three hundred years old, the ceilings low enough that they grazed her head. She ordered scampi and salad. Peeked at other tables, examined their orders. Smoked kippers and brown sauce, potatoes weighed out in a pale Cullen skink. Two men, still in their slicks, had battered sausages, yellow chips. At their feet was a damp Labrador, nose held high. One of the men peeled some batter from the sausage and slipped it to the dog. Davy. Death was not easily remembered, she’d realized early on. She’d bought tins of his food at the supermarket, filled his water bowl. Living was a routine he had to be edged out of. His possessions were gradually bagged up and left in the garage.

The scampi was good. Langoustines come in off the boat this morning, the waitress had promised, you can’t get better than that. A tattoo of what looked like a garden gnome winced on her forearm. She was young, although at 55 Ronnie could no longer tell how young. She returned with Ronnie’s pint. There you are. Thanks. The waitress clasped her hands together. Anything else? No, thank you. Ronnie spoke again as she turned to leave. You live around here? Yeh, literally here, I’m upstairs. She pointed to the ceiling. Ah, nice. Not really, the waitress shrugged, gets a little crowded. Right, right.

Ronnie’s friends, Ellis and Kay, wanted her to meet somebody. To them, Davy dying was a sort of sign. Celestial, ordained, finally, they were at last allowed to say what they’d always thought. It was nice to have a pet, but really, get out in the world. Ronnie had gone on the apps after bottles of merlot, the pair of them bent over her phone and giggling, wondering why she didn’t have any decent photos of herself. Because there hadn’t, Ronnie had said at the time, been anyone around to take any!!! She’d meant it as a joke. Debbie had left four years ago, or five, maybe even six? There had been a few dates, a few fucks.

The waitress returned with another pint. Ronnie tried to stack her plates helpfully. A fork dropped to the floor. The men in slicks looked over, the Labrador stood gallantly. I’m sorry. No stress. The waitress bent to pick it up. The waistband of her trousers pulled wide across her hips. Another tattoo, this one a cartoon sun, or was it a clown, sat poised on the last rung of her spine. You want pudding? I’m good, thanks. Ok.

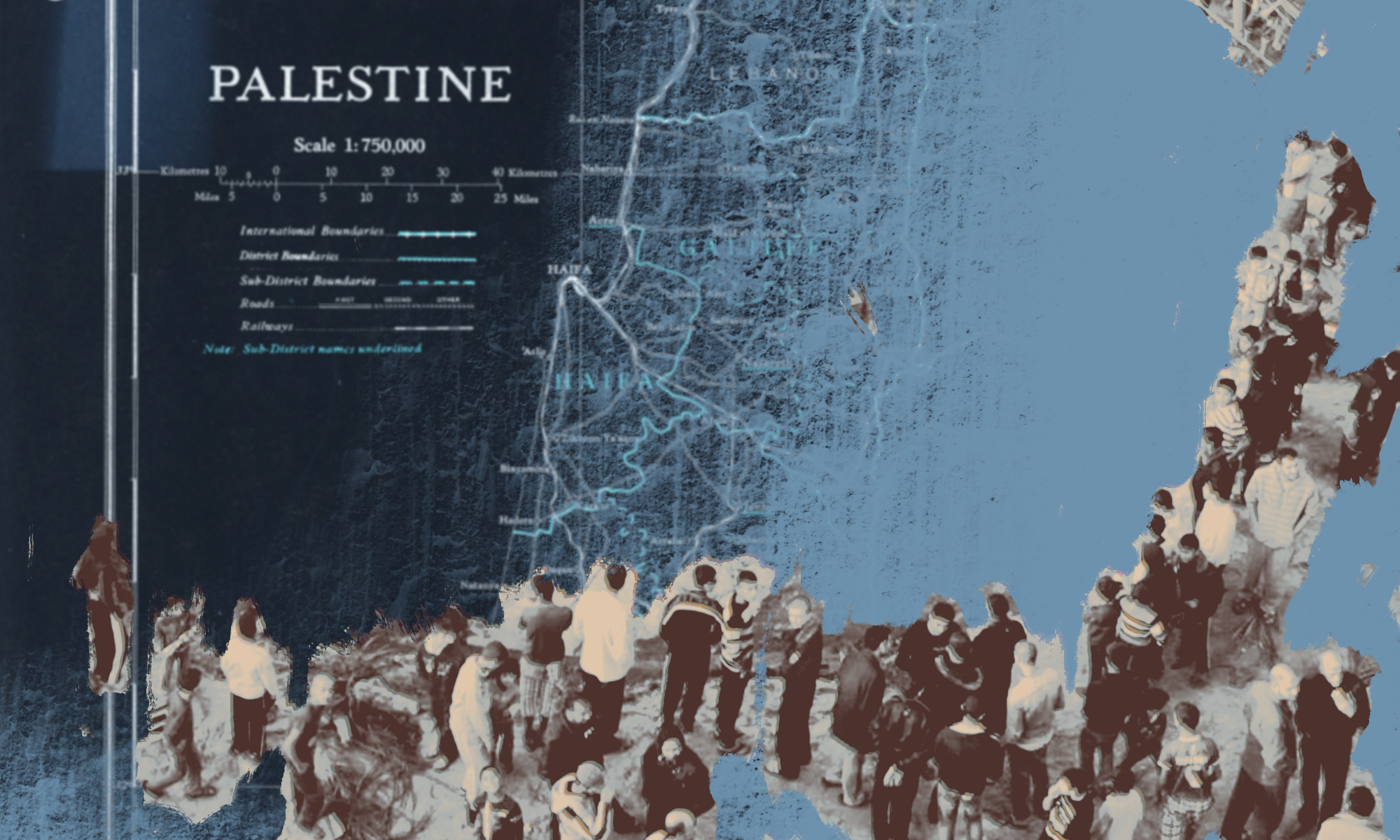

Ronnie swiped past her screensaver of Davy. Googled the hotel again. Saw she’d missed, in the menu bar, a subtitle in cursive caps lock, MEET OUR GHOSTS. Clicked through to find blurry photos. One, taken from the street fifteen years ago, showed a smudge with eyes in a top floor window. Another, remnants of jagged glass, a broom threatening against a clapboard wall. There were testimonials, too. Mostly women, only women, Ronnie clocked as she scrolled. Presences were described in detail. Some shivered and then promptly saw a gray figure at the end of a corridor. Brenda from Edinburgh had woken at 4 a.m. and felt somebody get into her bed. After a few hours, whatever it was climbed back out, leaving behind a distinct dint in the sheets. When she’d touched the dint, it had been warm. No, Brenda had disclaimed, she wouldn’t stay again. But yes, it did feel special to have been chosen. A separate paragraph confirmed the woman behind the desk’s theory. A husband and wife, unnamed, had lived in the house. Their youngest daughter, one of four, had drowned in the harbor, knocked in after an abnormally high tide.

A text arrived from her mother, who was alive. Ronnie opened it. Saw a picture of a pink and white flower. Her mother exclaimed underneath: The naked man orchid!!! This text was followed quickly by another, which was only a winky face. The orchid had a tiny penis, a soft looking lobe dropped between two short petal legs. Dash marks near the stamen looked like a shocked face. Ronnie sipped her pint. Omg! she replied.

The waitress was slow to return to her table. Instead Ronnie went to the bar and waited. A third pint would be fine, it was her holiday. The bar was made from wood, resplendent with dark whorls, the varnished surface sticky to the touch. She thought of other things that she could have messaged her mother: who do you think that’s supposed to attract?! Size isn’t everything! Not my cup of tea!

Another, please. She tapped her empty glass. Sure thing. Ronnie’s mouth had slackened but she was not yet drunk. She’d always been able to hold her beer. She looked longingly at the Labrador, who had fallen asleep with its head between its large blonde paws. The food had been cleared. It could finally relax.

Debbie had loved Davy. She’d thought about emailing her when he died, had saved a few drafts, but could not reduce her feelings efficiently enough. Debbie had been good at that, a self-proclaimed clear communicator. Was quick to blame Ronnie’s long and confused silences on her star sign. As an Aquarius, you’re so prone to this, you have this whole world in your head and no one else is on the guest list. It had been a relief to be described by somebody else. Ronnie felt hung on a wall, occasionally admired. Debbie had even done Davy’s chart. Gemini rising, Ronnie couldn’t remember the rest, but that part had pleased Debbie. My little charmer, my little creeper, Debbie would say, and he’d skitter over, twist into her legs, request that she scratch a particular spot beside his tail.

Ronnie drained the last of her drink. Entered the weather bolstered.

The hotel entrance had a sort of lounge. There was a bar, too, but it would not open until 6 p.m. Shelves of worn novels and a framed poster of an attributed John Waters misquote, “don’t trust ’em” if they’ve got no books on their shelves! Ronnie could not remember exactly how it should read, but knew it involved fucking. Wondered if it had been purposely censored, or if the phrase had been altered by somebody else, maybe even a series of different people, all of whom imagined John Waters to be a mild poet, or philosopher, or lifestyle guru. She picked a book. A collection of local oral histories. Between the first pages found a curled white hair, pulled it free and let it float to the royal blue carpet. The woman behind the desk had left. In her absence there was a number to call if you were checking in late. She’d left her water glass, a lipstick mark clear across the rim.

Her mother texted again. Howz the hol? She’d always loved Davy, announced it loudly, obsessed over his little red jacket, addressed him directly, you’re my favorite grandchild, my only grandchild, I suppose you’ll have to do.

Ronnie did not take a breath up the stairs. She went quickly down the corridor and unlocked her room. At the bathroom door she paused. Remembered the toothbrush. Like a child scaring off a monster she clapped loudly before entering the white-tiled room. She reached for the light and hit the fan. Leapt at the heavy whir. The toothbrush was where she’d left it. The jumper, too, balled into her duffel.

Once again she was imprisoned by the green numbers of the alarm clock. She closed her eyes, looked back, found herself only a minute in the future. She would go to the bar at 6. In the meantime a headache threatened. She took a painkiller, downed another glass of water, hummed to block out any extraordinary noises.

At 5:58 she rose. Back twanging. Changed into a shirt. Outside the purple light had faded to black. She reset the heating. Figured she might sleep with the radio on. Stuff the other side of the double bed with pillows. She checked her hair in the mirror. Considered, at Ellis and Kay’s request, taking a selfie, one to better her chances online. Her white sweep of hair hard-set with wax, immovable. During the short time she’d spent on the apps, she’d been categorized as a silver fox, the old guard, a butch daddy, a butch grandaddy, TERF?

A few ducks, beautiful, sauntered up the wet street. In the streetlight the male, with his color-blocked head, looked like a puzzle piece.

She took a picture of the empty bathtub and sent it to her mother. Relaxing!!!

The bar was in an old and ugly extension out back. Ronnie thought she could smell gas. Above the row of gin bottles, a piece of plywood read THIS WAY TO THE BEACH. Shells lined the damp windowsills. Along the walls were small paintings of frogs doing various summertime activities. Building sandcastles, surfing, wearing sunglasses. Each thick with color and signed GREGG in huge capitals.

A teenage boy was on duty in a stiff white apron. He acted like he was in a movie, vintage Tom Cruise, a tea towel slung over one shoulder. What can I get you? Four piña coladas. He frowned. Ok. Only kidding, I’ll have a gin and tonic. Ok.

Ronnie was not alone. A couple tittered in one corner. Nearer to the bar, by the screen doors that would in summer open onto a small patio, she spotted the woman from the desk. She’d changed, wore a different necklace, a dress decorated with yellow moons and stars. The boy slid Ronnie’s drink towards her. She tasted it. Don’t suppose you’d top it up? He reached for the open bottle of tonic. No, with gin. Oh I can’t do that. Sure you can. I’ll have to charge you for a double. Do what you’ve got to do. He measured out another pour with careful hands, dribbled it in. It won’t all fit, there’s still some left, he blinked, I can save it for your next round? Ronnie reached across, took the measure from his pursed fingers, and downed the rest. You can’t do that. Too late. She felt bad enough, though, to tip him a fiver.

The woman from behind the desk raised her glass. Bit early for shots? Never. Ronnie approached. Leaned over the small table to cheers the woman’s white wine. Is he Gregg? What? Ronnie pointed to one of the frog paintings that hung above the woman’s head. In this one, the frog rollerbladed while licking an ice cream with a long, thin tongue. Oh, you know I don’t know. The woman called across to the boy. Are you Gregg? No, I’m James. He arched his hand against his chest. Mystery solved. Well, unsolved. We’ll never know who the real Gregg is. I’m sure I could find out, I know people. The woman winked again.

Ronnie noticed an empty wine glass next to the woman’s full one. Allowed the silence that fell between them. The woman spoke first. I’m Jemima, Jem. Ronnie. Well sit down Ronnie, if you like, join me in my tragic after-work-at-work drinks. Sure. Ronnie edged into the soft armchair opposite. The woman had, Ronnie thought, a theatrical face, like a director of a school play, ready to show other people how to emote. A high, creasing forehead. Sweeps of bronzer up her cheekbones. Narrow brown eyes widened with mascara. Her jewelry had been reduced. Now she wore a long gold chain, a large turquoise pendant swung close to her waist. No bracelets.

You see, they give me a discount, on my chardonnay, hard to resist with what they pay me, it’s a vicious cycle, so I basically never leave. You live nearby? Ish, ish, I can’t afford to live in this town, only the terrible can, but you’ll find me half an hour that way. Jemima thumbed over her shoulder. Inland the landscape was arable. Dairy farms, organic vegetables, a spate of new breweries. Ronnie had driven through, felt depressed by the flatness. Had a fleeting image of Davy bowling through the wet green, overwhelmed by possibility, the way he was when she walked him over a football pitch. Each blade of grass, she’d understood, had an entirely different smell. A dog could tell the difference.

Jemima gulped her wine. And yourself? City life for me. Ah, very brave. Is it? I think so, in this day and age. Ronnie thought it was braver to perch amongst the fields, she wouldn’t know where to start, couldn’t light a decent fire, was afraid of cows. I like the city, keeps me busy. See now, Jemima still held her wine glass, unclasping one finger to point at Ronnie’s chest, I’m deeply against being busy, let me wallow, let me overthink, I’ll wander the desert alone.

Rain ticked on the roof. Ronnie looked up to see it was half plastic, that they sat under the plastic half. I can understand that, Ronnie replied. She couldn’t, though.

James the barman eyed them nervously. He looked over his shoulder as he unloaded a dishwasher full of glasses, wiping his brow as the steam rose. Jemima had a loud voice. It carried over his tinkering, the rain’s footsteps. So how do you like our little hotel? It’s very nice. And have you been visited yet? Jemima widened her small eyes. Oh, no. But you believe? In ghosts? What else! Plenty else, Ronnie thought to herself. But instead remembered a good stock reply and delivered it: I believe in something, that this can’t be it, you know?

Her mother had wept when Ronnie called to tell her about Davy. In fact, it was her mother who had called; Ronnie had only sent a text. She’d kept it formal, guessed at how a minister might message a member of his congregation. Mum, I’ve got some sad news: Davy passed away this morning, he was very peaceful. She deleted he. It was very peaceful. Her mother had rung almost immediately, what, she repeated, what, I don’t understand, what, how can this be. Ronnie explained what she could. That Davy had an epileptic fit and that was it. She’d left out that it hadn’t been peaceful, that she’d been stroking his head, a normal Sunday, when his body turned and wouldn’t stop turning. Each of his small valves suddenly open, bared to the world, that the beige, two-seater sofa could not be properly cleaned. A fit? A fit? Yes. Her mother had the phone on speaker. Would have been sitting in her armchair, pulling an old tissue out of her sleeve, Ronnie was convinced she could hear the scrape of skin as her mother’s fingers scaled her wrist to retrieve it. Her mother had blown her nose, added, at least he’ll be in doggy heaven now. Laughter had torn through Ronnie’s numbness. She’d managed to reduce it to a snort. The notion of Davy, who’d hated other dogs, who’d wanted only people, forced to frolic for eternity with all the Bozos, Rosies, Midnights, and Morags that he’d wronged on earth.

Spirituality, that’s what you’re talking about, that some part of us stays behind, that we can split, become a presence. Jemima planed a hand up her chest. Sure, sure, I feel that. Ronnie did, in a way. An image brightened in her mind. Her soul folding and unfolding like a bedsheet.

So have you ever seen the ghosts? Jemima took a deep breath through her nose. I wouldn’t say seen, it’s not that simple. No? No, it’s more a feeling, an imprint. Right. You don’t believe me. I do, actually. Jemima lifted her empty wine glass and flicked it. Another please, Gregg. It’s James. Then another please, James. She turned to Ronnie, who drained the last of her gin and tonic. Same for you? Yes, please.

Debbie had been spiritual. The question had come up on their early dates, Ronnie indifferent to the thought, but she explained her semi-religious upbringing, hammed up the rules in her childhood home, borrowed a scene from television in which an American family bowed their heads in a severe grace before each meal. After a couple of years Debbie’s spirituality had distilled into a kind of feminist paganism. She joined a group that met in a wine bar after work. Leather pouches filled with runes were bought online, a hand-painted tarot deck. At a party one night Ronnie had got it wrong, told a mutual friend that Debbie believed in Wiccan. Later, at home, when they’d been undressing for bed, Debbie had corrected her. I don’t believe in Wiccan, I am Wiccan, next time you feel like bringing it up.

Jemima and Ronnie watched James, Ronnie thought she saw his hand shake a little as he unscrewed the chardonnay. He made a point of placing the drinks on the bar so they would have to get up to retrieve them. Ronnie took a swig as she stood and faced him, gently unsteady.

I read about the woman on the website, the one who’d felt someone get into bed with her.

Jemima licked her bottom lip. Ah yes, I remember her. The wine glass in Jemima’s hand slipped a millimeter, the yellow liquid reached up and kissed the rim. She was very calm about the whole thing to be fair, and get this, she thought it might have been the wife and not the husband that got under the covers, can you imagine?

Well there’s your unfinished business, Ronnie slurred slightly. She felt each ‘s’ drop from her tongue. Had never considered a lesbian ghost before but sure, why not?

Jemima was slow to the joke, laughed, startled, after a long second. No, no, but listen, but really, this woman, god I can’t remember her name. Brenda. Yes, well done, Brenda, she’d only recently lost her husband. Grief, it creates this portal in you. Ronnie imagined a silver coin, a fifty pence piece, appearing where her belly button should be. We’ll see about that, Ronnie snorted, I’ll let you know in the morning if I’ve gotten lucky. Jemima dropped her head to one side, found the right angle to ask a personal question. You’ve lost someone? My Davy. Sadness threatened to rush out of Ronnie, that tragedy already written and shelved in the archive of her guts, some dank and Greek and horny play. Persephone? No, the other one.

I’m so sorry. Jemima’s head titled further. Was Davy your husband? She placed her elbows on the table, inched her chair closer.

The conspiracy of death, thought Ronnie, eugh. At the same time Ronnie felt Jemima look her over, double-check the possibility of a husband, ascertaining the unlikelihood. It was the scar through her eyebrow, Ronnie rubbed it with her forefinger, as she’d done since she was a child, her most lesbian bit. But there was also the hair, the stride, the barrel chest. My Davy. Ronnie’s body paused. A different piece of music swelled in her. She looked at the floor, saw it was linoleum made to look like wood. Davy, that was my wife, a nickname, you know, just between us. Each word out of her mouth like a spring that wouldn’t uncoil. Gin, it was gin she could not handle. Beer before gin is never a win. Gin before beer, hooray you’re queer. She rhymed in her head, proof she couldn’t be too drunk, not 100 percent. Closed her eyes just for a second.

God, I mean, that’s one of the worst things that can happen to a person, I really am very sorry. It’s ok, I’m ok. Ronnie held out her palm like a stop sign. Was it recent? Jemima got closer to the table. The orange LED candlelight reflected in her pupils. Last month. Oh God, I’m so sorry, were you together a long time? Ten years. That’s amazing, that’s incredible.

Eurydice, it was Eurydice Ronnie had meant, not Persephone.

Jemima sighed. At times like these I wished I still smoked. Ronnie, who had never had a cigarette in her life, agreed. She let her lies bloat into a Venn diagram, pain at the center. Here’s to those we’ve lost. Jemima offered her glass in a cheers. You too, you’ve lost someone? I mean, I’ve never been married, but I had this boyfriend, we were only together a few months, then he died suddenly, an aneurysm they said.

My Dad died of an aneurysm. This, at least, was true, Ronnie’s father collapsed twenty years ago walking home from the pub. It had been autumn, he slipped into a ditch, brambles vaulted above him. Jemima wrapped her hand around Ronnie’s. That must have been tough. It was, but a long time ago now, much harder on Mum, you know. Ronnie’s father had been a particular kind of cruel, liked to leave a dead sparrow in the cutlery drawer, to dig his fingers into Ronnie’s ribs when he passed her in the kitchen. She learned to walk with her back pressed to the wall.

Jemima patted Ronnie’s knuckles with her fingertips. To me, I don’t know, when Morris died, that was my boyfriend, I kept thinking how death, it can make you feel fake, I felt fake when he died, like I was doing it wrong, that I was way too sad and then not sad enough but maybe that’s because we weren’t together that long? I hadn’t even told him I loved him, I don’t think I actually did, the memory’s a mess isn’t it? But when he died all I could think was, I probably should have told him I loved him anyway, even though I didn’t. Jemima put her head in her hands. Is that completely nuts of me?

No. Ronnie was definite. No. Relieved to almost have another lie in circulation. It’s ok to say something that makes you feel good, and you’re making someone else feel good, it’s harmless. I suppose so. Jemima kept her head in her hands, massaged her temples with her thumbs.

I didn’t feel fake, I don’t think, when Davy died, when she died. No? Ronnie wanted to make herself completely clear, as transparent as a window, but it was difficult. Her brain bobbed. That moment in the vet’s, when Davy had passed, and she’d wanted to see him one last time, his small pink tongue poking out where the tube had been inserted, she’d felt the opposite of fake. Reality filled her body like cement. Or maybe I did, feel kind of fake, I don’t know, there’s no real help, no real guidebook, death is a made-up place.

How true, yes, Jemima nodded nobly, we’re all just making it up as we go along. Ronnie sucked an ice cube. I know I am. The couple in the corner had left. Ronnie tried to see the clock above the bar, to the right of James’s combed hair. She squinted, felt the bottles move. Couldn’t make out the numbers. Here, here. They cheersed again. She wasn’t sure what for.

Jemima sat close enough now that Ronnie could smell her breath. Wine, the cure of her tongue. Jemima sighed heavily. Listen, listen, can I ask you something personal? Sure, why not. Ronnie’s mind wandered, the scene in front of her a little bleary, she tried hard to narrow her internal vision, challenged herself to think of a lesbian ghost but came up short. Realized, in that moment, she could not think of any living lesbians, either, except herself. And Debbie, miles away, or not, she had no idea where she lived now.

Do you think, you know, do you think you could be with someone again? After what’s happened? Ronnie squinted. You mean sex? No, God, no, I meant marriage, although. Jemima took a heavy pause and Ronnie watched her enjoy it, the weight that settled between them. Although, I guess marriage should mean sex. Most of them don’t. Well, I wouldn’t know, I’ve never been married. And why is that? Ronnie’s line of inquiry sharper than she’d intended. Why haven’t I been married? Now there’s a question, how long have you got. Jemima did not punctuate her question. She turned over her hand, investigated the lines.

Sorry, you don’t have to answer. No, it’s fair game, I brought it up I suppose. Jemima looked off to the side, through the conservatory plastic, which dulled even the rain, the oily streetlights. Ronnie followed a speck, a person in a red coat, as they walked fast up the cobblestones. It’s not that I don’t believe in marriage, it’s not some grand moral thing, although maybe I should start saying it is, honestly I just never had the energy to do it, it’s something you have to constantly give energy to, not even the marriage itself, just the fucking buildup to it, to keep the relationship moving, my God. Jemima spread her arms wide. I could never do it, quite simply, wasn’t for me.

Ronnie dredged up another of her mother’s phrases. A couple is in a rowboat. What? Hang on, one sec. She saw her mother’s face as it was now, her skull beginning to show, the air gone out of her. But Ronnie was a child, her old mother’s face spoke to the child Ronnie with her crisp mouth, and child Ronnie, by comparison, had pink, soft cheeks, a scar healing through her eyebrow, she could feel the tug of newly healed skin. A good relationship is like a rowboat, you both have to be pulling in the same direction. The image floated in her brain like a loose negative. She tried to focus on Jemima’s face. I don’t know, Mum used to say that to me. Jemima whistled through her teeth. Sounds arduous. I always thought so. Jemima’s arms stayed wide. It’s the capitulation I can’t stand. Right. The size of the word, capitulation, bore down on them both. Throw me overboard, just let it be over, for fuckssake. As she spoke Jemima threw back her head, rolled her eyes. Ronnie found it thrilling, the long exposure of her neck.

God, Jesus, fuck, that’s insensitive of me. Jemima returned her head with a snap. Why? What do you mean? Well, you know, you’ve, your partner is dead, your wife.

Dead. No one had said it to her face, since Davy, sweet Davy, with his peculiar proximity, his desire to be close to her but not cuddled, that he was dead, an absolute, a whole thing, the circle drawn shut. Dead. Ronnie laughed because it had not occurred to her. Jemima frowned. Ronnie bent over in her seat, wheezed, the lid in her knocked loose. Jemima caught on, inhaled and snorted, let out sighs of pleasure, the kind that can only come when you’ve reached the very end of your body. Oh, Jemima wiped a tear from underneath her eye, I needed that. Ronnie thought of Orpheus’s song for Eurydice and all the effort that goes into a voice, any voice. Eurydice, which she had always pronounced Uri-diss, and was most likely the wrong way to say it. E-ury-dice. Er-uri-dy-cee. Even Davy’s gorgeous little bark and its nonstop rotation, it had been his, he’d made it happen.

To answer your question, Ronnie stuck out her chin, I don’t want love, not anytime soon, but I am fine with sex. She heard the thud of her failure even before Jemima’s response. A finessed intuition, she noticed Jemima sat up straighter, receded into the fabric of her seat. Jemima lowered her eyes before she spoke. Now, just to be clear darling, I don’t do fanny. Just as well that’s not the only option then, Ronnie joked. There are other holes, was what she’d meant, different portals, but couldn’t get the specificity to land. Now she’d missed her chance to make the joke properly. Jemima already laughed again, this time her pitch was off. Well, I won’t dare ask what you mean, that’s above my pay grade. She waggled a finger at Ronnie.

The amount of holes a person could fall through! Ronnie’s laughter surged and subsided. Debbie had been the first person to fuck Ronnie in the ass. A small-ish purple dildo, rehearsals of miniature butt plugs. A feeling like flying, of forms parting, becoming the quivering outline. Or maybe, Ronnie thought now, shifting in her seat at the memory, not quite flying but diving, heading towards the molten core. It had slipped at first, poked the rise of Ronnie’s thighs, but Debbie had quickly righted. She was good like that. Calm, committed. She had been nice, Debbie. Maybe Ronnie should get in touch, tell her about Davy, Debbie had loved Davy. Write her an email and explain it all, carefully, clearly.

Jemima stood. One more for the road? She lifted her empty wineglasses with spider precision, fingers outstretched, pressure exact, four in one hand. Oh bartender! James turned. Slicked down a stray hair. That’ll be last orders, ladies. The good man has spoken, get in while you can, same again? Ronnie’s stomach wouldn’t take it, she knew, could feel the edge of her memory, the sea below. Yeh go on. He was so young, James, he could barely say “ladies.” Ronnie could give him all sorts of advice. Jemima blew him a kiss as she took the drinks. Thank you, darling. He smiled blandly and picked up his phone, sipped from a pint he’d poured himself at some point.

Jemima waited mid-air, chardonnay poised for another cheers. Here’s to our demons! May they be generous enough to carry us away! Ronnie caught a draft, shivered, wondered about the husband and wife, then her toothbrush, and where they might have moved it.

She was aware of Jemima’s proximity, Jemima who wanted to cheers with their arms linked, the crooks of their elbows touching. Ronnie almost dropped her glass. Managed to get it to her lips for a few seconds before Jemima jerked her further forward. Jemima wanted to down her wine in one. Regret, I never knew her. Jemima spoke her line quietly, pressed her empty glass to her cheek. She was taller than Ronnie, in heels maybe, close enough now to breathe in the top of Ronnie’s head.

James had chosen music on his phone, balanced it on a stack of napkins. Fast, chaotic guitars. A strained and melancholic male voice, nasal, with a point to make. He smacked the lights on. The bar, their faces, in full view. That’s it ladies, he affirmed, time to go home. They blinked, adjusted, Jemima extracted her arm. Well then, that’s us I suppose. Ronnie nodded. Yeh, that’s us.

It was nice meeting you. Jemima did not extend her hand, did not move at all. Only her gaze was left lodged between them. It was vast and blank, a space Ronnie thought she ought to fill. So she lunged forward, kissed Jemima with the full force of a bird hitting a glass pane. Jemima’s mouth opened a millimeter, then closed. Ronnie’s lips fluttered and failed. Sorry, I’m sorry. No, no, Jemima waved her hands, it’s fine, maybe I was thinking the same thing. You were? Well, no, but, in another life, a parallel universe, who knows. Right. The next track played from James’s phone, this time two male voices. One rapped, another sang, higher and higher, it was kind of ecstatic, Ronnie thought, then the drums, seeing the voices out, both left to shout, no scream, over the snare, the thrash.

This is me, I’m this way. Jemima walked towards the patio doors. James, if you wouldn’t mind. He sighed, selected a key, released her into the wet night. Ronnie waved, watched Jemima plant each heel delicately between the cobblestones.

Ronnie tried to draft Debbie’s email. Debbie! Long time no speak, Debbie! Hello from the other siiiiide, Debbie! She paused at the threshold between the bar and the hotel reception. Listened. Nothing listened back. There was the acute sense of somebody else, the husband and wife, that they were looking on from a specific elsewhere, a perfect nothing, a heightened nothing. Along the textured wall, the high skirting, she spotted little green circles. She joined their orbit, realized they were glow-in-the-dark stickers so guests could find the switches. She turned on a lamp. The nothingness did not recede. More and more shadows, the Johns Waters misquote, the marked rim of Jemima’s water glass on the desk. She paused again at the stairs, looked up the dark tunnel. Debbie! This might seem out of the blue. Debbie! I know it’s been a while. She tripped halfway up, her phone slipped from her pocket. She breathed heavily, checked over her body, rotated her ankles. Nothing broken. Only her knees burnt on the carpet. The sing-song of grazed skin.

Crawled on her belly and retrieved her phone. Saw her mother had sent a purple devil emoji, frowning pleasure. Ronnie could not remember what it was in response to. Replied slowly and carefully with a plump chick.

She stood clumsily, gripped the banister. The corridor was what they liked, the husband and wife, she was surely prepared to meet them, her body thrilled at the anticipation, like waiting for a kiss on the forehead, Jemima’s kiss. She hoped she’d get home safely. Was she walking, out there in the rain?

At the end of the corridor was a soft glow. Ronnie grunted, this was it, the ghost couple, their sad dead daughter, who had never come back to find them. Thought she should film it then fumbled her phone again. Crouched to find it, tipped to the left, righted herself, kissed the screensaver of Davy. When she looked back at the soft glow she saw it was a nightlight. Laughed. The flavor of her fear was boiled gin, boiled beer.

Managed the door to her room, just. Left the key in the lock. Forgot the logic. Pulled out the green jumper and wrapped it around her shoulders. Would count the Davy hairs if she could. Lesbian ghosts, what lesbian ghosts? Which dead lesbians? She found some Emilys. Emily Brontë, Emily Dickinson. Others. Woolf, Dietrich, Baker. Lesbians had died, plenty of them.

Debbie! I miss your cock in my ass. Debbie! Remember Davy? Well.

Ronnie felt the laboring of her chest. The alcohol had tightened her lungs, she was full to the brim. Touched her fingers to her lips and tried to imagine how they felt on somebody else’s mouth. It tickled the inside of her, she bit down, blocked the sensation. When she was young she’d had friends at school who she’d wanted to kiss. Recalled, those trilling girls, they’d made a Ouija board together out of cardboard. It had only two answers, YES or NO. Fingertips placed on an upturned tumbler, they’d coughed out hysterical questions. Believed in the supernatural pull of the glass. Yes, no, yes yes yes. Better, dozed Ronnie, better to talk that way, in the language of the dead, full sentences long gone, only waiting to be asked the right thing.