Even outside India, it can be difficult to escape the cult of Mohandas Gandhi, the lawyer, thinker, and politician who helped liberate the nation from British colonial rule in 1947. The praise ranges from the anodyne (Gandhi is a “hero not just to India but to the world,” per Barack Obama) to the ironic (“really phenomenal,” according to Burmese political prisoner turned genocide defender Aung San Suu Kyi) to the surreal (“I am Gandhi-like. I think like Gandhi. I act like Gandhi,” declared New York City Mayor Eric Adams). Seventy-six years after his death, Gandhi is not only an icon of Indian independence, but a uniquely potent international symbol of peace and nonviolence. Gandhi has been, at one point or another, as historian Vinay Lal puts it, the “patron saint” of “environmentalists, pacifists, conscientious objectors, non-violent activists, nudists, naturopaths, vegetarians, prohibitionists, social reformers, internationalists, moralists, trade union leaders, political dissidents, hunger strikers, anarchists, luddites, celibates, anti-globalisation activists, pluralists, ecumenists, walkers, and many others.” Everyone, it seems, has endorsed the honorific coined for him more than a century ago: Mahatma, Sanskrit for “great soul.”

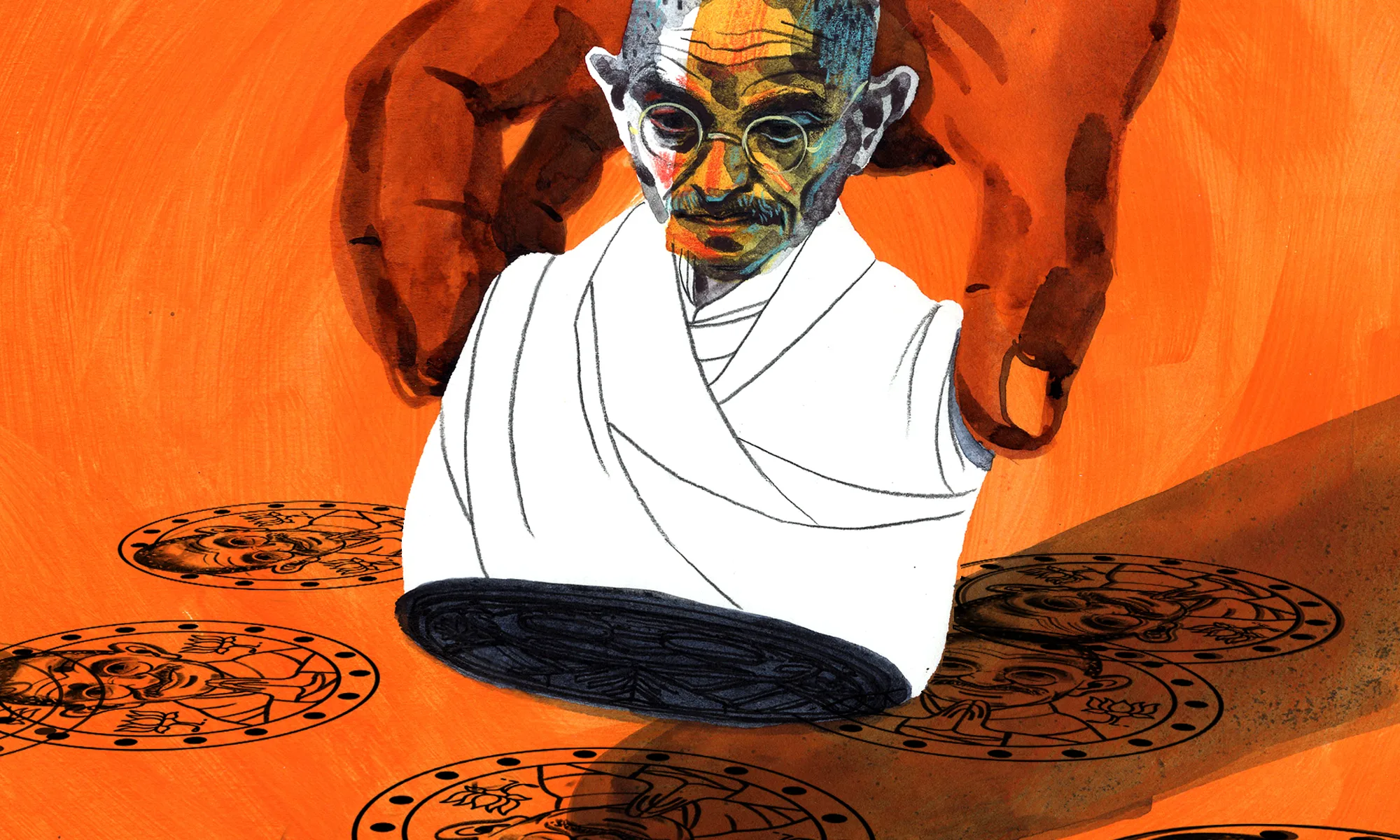

Within India, Gandhi graces every banknote and is plastered on billboards and painted on walls alongside busy thoroughfares. His bespectacled face looms over big cities and small towns alike. Countless schools, universities, roads, and public spaces are named after him. In 2013, the government of Bihar, India’s poorest state, spent several million dollars building the world’s tallest Gandhi statue, casting him in a shimmering tower of bronze with two grateful children by his side. Public figures fight to outperform one another at Mahatma-loving, something of a national sport: in 2021, one representative viral video captured a regional party leader clinging to a bust of Gandhi and sobbing. But Gandhi’s ubiquity masks the fact that among political actors, commentators, intellectuals, and a growing swath of the general public, his reputation is far from settled.

The lead-up to a general election this spring — in which the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is likely to beat out the centrist Indian National Congress Party and be reelected for a third straight term — has brought dueling visions of Gandhi to the fore. Congress, which was helmed by Gandhi himself on the road to independence, still hopes to capitalize on its historic connections to the Mahatma, but the efforts of its increasingly ossified leadership are falling flat. Meanwhile, the BJP pays lip service to Gandhi’s brand while vigorously working to counter his core values, including, most crucially, his lifelong pursuit of Hindu-Muslim unity. The far-right fringes go even further than the official party line: in some circles, Gandhi is belittled, mocked, burned in effigy. This confused state of affairs suggests that a reckoning with the competing narratives swirling around Gandhi is long overdue. Even as he has been flattened into an ill-defined figurehead by liberals and centrists, his complex legacy is being appropriated — and at times desecrated — by India’s seemingly unstoppable right.

In the popular imagination, Gandhi evokes austerity and simplicity. But despite his humble appearance, Gandhi came from a fairly well-off family in Gujarat and, like many Indian elites, studied abroad in England: in his case, law at University College London and the Inner Temple, a prestigious barristers’ association, which put him in a rarefied social echelon. But he was less straightforwardly patrician than someone like India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, a graduate of London’s distinguished Harrow School who once reportedly described himself as “the last Englishman to rule India.” Gandhi’s aesthetic was, instead, self-consciously Indianized, an elite performance of sympathy with ordinary people. In 1921, he pointedly gave up his barrister’s suits for a humble dhoti and shawl made from the hand-spun cotton he championed in opposition to foreign textiles. (On a visit to London in 1931, Gandhi even wore this uniform for tea with King George V at Buckingham Palace.) His political vocabulary, which drew heavily on Sanskrit, similarly allowed him to straddle the divide between the masses and India’s so-called Lutyens class of Anglicized elites. The most famous of his Sanskrit-derived neologisms might be “satyagraha,” or truth force, which Gandhi used to refer to his style of nonviolent resistance; other religious terms he popularized include “swadeshi,” or self-sufficiency, “swaraj,” or self-rule, and “ahimsa,” or nonviolence. His conception of an idealized form of egalitarian and democratic government was, he said, a Ramrajya — or kingdom of Ram, an important Hindu deity.

Gandhi developed his theory of nonviolence in the process of organizing against the systematic oppression of Indians in South Africa, where he worked as a lawyer before beginning his political career. He moved back to India in 1915, having already established an international reputation as an activist. There, he threw himself into the independence movement and joined the Congress Party, which he would steer, along with Nehru, for two decades. Congress had until then been a somewhat minor political force; Gandhi broadened its appeal, realigning the party away from its elite base and toward a mass audience by making heavy use of Hindu rhetoric and symbols. But while he relied on religious concepts to popularize his independence platform, Gandhi simultaneously mounted a critique of religious orthodoxy and caste inequity. He campaigned fervently against the designation of a group of people as “untouchable,” or so low on the social ladder as to be considered outside the caste system. (Gandhi himself was from a well-off merchant caste.) After World War I, Gandhi began to focus on overturning British rule. In his famous Salt Satyagraha in 1930, he led a group of followers on a 240-mile march to the sea in protest of the colonial government’s monopoly on salt. The authorities arrested some sixty thousand demonstrators. Gandhi also worked to unite Hindus and Muslims, who had often clashed on the subcontinent, believing that joining the two groups together would make a strong case for an independent, pluralistic India. Not everyone endorsed this vision: the founders of modern-day Pakistan advocated successfully for a separate, Muslim-majority nation. When independence was won, the 1947 Partition of India created India and Pakistan and led to the death of between two hundred thousand and two million people in communal violence and riots. Gandhi spent Independence Day fasting — one of his key satyagraha tactics — in Calcutta.

Gandhi’s pluralism faced opposition not only from the Muslim leadership of Pakistan, but also from the religious right within India. Hindu nationalists espouse the ideology of Hindutva, which envisions a powerful and assertive Hindu nation that subordinates other groups. Gandhi’s Hindutva critics believed his conciliatory approach had led to Partition — along with the creation of Pakistan in what they felt was intrinsically Indian territory — and looked down on his efforts to promote religious tolerance. In the words of a key architect of Hindutva, Gandhi was a “sissy.” A major organ of Hindutva is the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a volunteer paramilitary group founded in 1925, and it was a 37-year-old RSS affiliate named Nathuram Godse who assassinated Gandhi on January 30, 1948. At his trial, Godse blamed Gandhi for failing to stop Partition and then failing to protect Hindus against the subsequent religious violence. An estimated million and a half people attended Gandhi’s funeral, and Godse was hanged for his crime, but the RSS lived on. (In court, Godse baselessly claimed that he had left the RSS by the time he killed Gandhi, a dubious line the organization held for decades; at any rate, Godse was an ideological product of the “Sangh Parivar,” the term for the various Hindutva organizations spawned by the RSS.) Today, the RSS’s membership is believed to number at least five million, and the Sangh itself has ascended to a level of power that would have been unthinkable in 1947: it is the umbrella organization encompassing the BJP — the party of Modi and, today, the largest political party in the world.

A recent Washington Post opinion piece called Gandhi “irrelevant” in “Modi’s India,” but the former leader continues to haunt this year’s election and Indian politics more broadly. Senior Congress member of Parliament Rahul Gandhi (no relation) recently described upcoming elections as a Gandhian face-off: “On one side, there is Mahatma Gandhi,” he said, “and on the other, there is Godse.” Congress President Mallikarjun Kharge likewise has said that defeating the BJP would be “a true tribute to Mahatma Gandhi.” Congress still regularly deploys Gandhi-style hunger strikes and marches, like 2022’s Unite India March, a massive campaign event intended to draw attention to the BJP’s exclusionary politics. Echoing the Salt March, Congress grandees walked over two thousand miles. A sequel, the Bharat Jodo Nyay Yatra, is currently underway; its route, from the east to the west sides of the country, covers fifteen states.

Yet the desire to be associated with Gandhi is not limited to his own party. The BJP paints itself as the inheritor of Gandhi’s values rather than the spiritual home of his killer, rewriting history in the process. Since the BJP’s victory in the 2014 general election, the National Education Council has removed inconvenient facts from high school textbooks, like that Hindu nationalists opposed Gandhi’s pursuit of peaceful Hindu-Muslim relations, and that the RSS was briefly banned after his murder. Modi rarely misses the opportunity to praise Gandhi in speeches and op-eds, and frequently visits the Raj Ghat, Gandhi’s memorial in New Delhi. India’s vice president has even directly compared Modi to Gandhi, whose iconic round glasses are featured in the logo for Modi’s Swachh Bharat (“Clean India”) sanitation plan. Modi has also claimed Gandhi as the inspiration for signature policies like the Atmanirbhar Bharat (“Self-reliant India”) campaign aimed at making India’s economy less dependent on international trade, a concept that echoes Gandhi’s notion of swadeshi. Modi and his government have a keen awareness of their obligation to sing the praises of a man whose most fundamental ideas they largely despise: Gandhi’s moral force and popularity among most of the public is simply too immense, and his position in India’s founding mythology too great, for the country’s leadership to be able to cast him aside openly and definitively.

But since the BJP solidified its majority and won a landslide reelection in 2019, Modi has gone beyond mere surface-level iconography to claim Gandhian precedent for distinctly non-Gandhian ends. On the most recent anniversary of Gandhi’s 1942 “Quit India” speech, in which he called for the end of British rule, Modi announced his own call for action, twisting the uniquely Gandhian phrase for his usual populist and anti-Congress messaging: “Corruption Quit India. Dynasty Quit India. Appeasement Quit India.” (The dynasty refers to that of Nehru, whose daughter Indira and grandson Rajiv have both served as Congress prime ministers. Appeasement connotes what the right sees as Congress’s kowtowing to religious minorities.) Modi has even said that the Citizenship Amendment Act of 2019, which fast-tracks citizenship for religious minorities like Buddhists and Sikhs — pointedly leaving out Muslims, a definitively un-Gandhian move — was an example of doing “Gandhiji’s bidding.” (The suffix “-ji” is a sign of respect.) Meanwhile, the Gandhi Memorial and Museum, which is run by a Modi-chaired government body, dedicated a special issue of its magazine to the leading Hindutva thinker Vinayak Savarkar, a major influence on Gandhi’s killer Godse. And in 2023, the BJP bulldozed the Sarva Seva Sangh, an educational institute founded to commemorate Gandhi, over a suspect ownership claim from the state railway authority.

Underneath the visible edifice of official policy and messaging, the broader Hindutva base has been quietly working to erode Gandhi’s popular support, even glorifying his killer. BJP parliamentarians have recently called Godse a “patriot” and a “nationalist.” In 2019, a regional leader of a militant Hindu group hosted a public event in which she ceremonially shot and burned an effigy of Gandhi on the anniversary of his assassination. “If I was born before Godse, I would have shot Gandhi myself,” she told The New York Times. Others have attacked Gandhi’s vaunted ideal of secularism as the product of an out-of-touch elite that pandered to minorities and nearly wrecked the fledgling nation of India. Secularism, in the Gandhian sense, does not entail separation of church and state — a practical impossibility in a deeply religious country — and is instead understood as the equal treatment of all religions, a concept anathema to the right. (“Sickular” is a common term of Hindutva abuse.) Gandhian nonviolence, the taproot of one of history’s most successful strategies for mass resistance against colonialism, has also been attacked as a sign of weakness. To Hindu nationalists, nonviolence is a remnant of colonialism, evidence that it was never truly purged from the country. Modi, who frequently plays up his humble origins as a tea seller’s son, has often promised to free India of this purported baggage — calling foreign rule “the time of slavery,” arguing that Congress has absorbed the Raj’s “slave mentality,” and asserting that India will finally break these shackles under his government.

Because the Hindu right has established a stranglehold on Indian media through legal harassment, buyouts, and government advertising sponsorship — in a recent survey, fully 82 percent of journalists characterize their employers as pro-BJP — Indian television, newspapers, and websites are able to amplify the BJP’s twisted appropriation of Gandhi’s legacy with little pushback. On one of India’s most-watched English news channels, the anchor Arnab Goswami accused Congress of “trying to own Gandhi-ji’s legacy,” and “using the Godse card,” or pointing out the connections between the BJP and Gandhi’s killer. The clip was posted on YouTube, where commenters drew out Goswami’s subtext, using an alternate spelling of Godse’s name: “Gandhi was a spineless leader where as [sic] Nathuram Godsey was a real patriot,” one person posted. “We proud of godsey,” wrote another. “Long live RSS,” a third added in Hindi. Even if Gandhi himself is too totemic to attack directly in the mainstream media, the BJP’s journalistic accessories have found ways to undermine him and normalize the most extreme views on the Hindu right. Prominent media personalities frequently attack Gandhi’s character and his morals, focusing on what they see as his over-friendliness to Muslims and relationship to the Anglicized ruling classes. One regular commentator on pro-government TV channels, Anand Ranganathan, tweeted a video to his million followers on Gandhi’s birthday, a national public holiday, gleefully listing Gandhi’s alleged crimes: racism, tests of his own celibacy that involved sleeping naked next to young women, and a craven disregard for the well-being of Hindus.

India’s cinema, which plays an outsize role in social and political discourse, is increasingly rewriting Gandhi’s history, too. Last year, the film Gandhi Godse — Ek Yudh imagined Gandhi and Godse sharing a prison cell and working out their differences, culminating in a scene in which Godse saves Gandhi from a different assassin’s bullet. The Hindu Mahasabha, a militant group associated with the RSS, clamored for the government to subsidize the movie by making tickets tax-free. As the organization’s national vice-president said, “Martyr Nathuram Godse has got a chance to speak in the film.” A hagiographic Savarkar biopic is also hotly anticipated. The 2022 global blockbuster RRR, moreover, pointedly omitted Gandhi’s name from a list of Indian revolutionaries. “The time has come to let Indians know the truth, the real warriors who should be honored,” the film’s screenwriter Vijayendra Prasad told The Washington Post. “Mr. Gandhi was not a bad man, but the praise that built up around him over the decades? Today’s younger generation are questioning it, because so many historical facts are coming out.” (The BJP rewarded Prasad’s work with a nominated seat in Parliament’s upper house.) The messaging seems to be trickling down. In a 2023 vox pop TV interview, a young man in the Hindi-belt state of Madhya Pradesh compared Gandhi to the terrorists who killed 175 people in Mumbai in 2008, because “both were dividing the country.” On X, one tweet noted in response to the video, “There’s no such thing as father of the nation, fucker.” It’s perhaps little wonder that at traffic lights and pavement booksellers in New Delhi, it’s not uncommon to see the transcript of Godse’s trial speech — published as a book called Why I Killed Gandhi — on sale alongside pirated copies of John Grisham and Paulo Coelho novels.

Between the far right’s villainization of Gandhi and attempts by both the right and the center to appropriate his legacy, it’s easy to forget that there are productive ways to think critically about Gandhi’s legacy. As the political left in India has declined to the point of near irrelevancy, and academic freedoms have been eroded by the Hindu right, Gandhi’s Marxist and leftist critics have been largely sidelined. But as the South African scholars Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed have pointed out, Gandhi’s writings from his time in their country indicate serious problems with his worldview. These early texts are replete with talk of a shared Indian and English “Indo-Aryan” stock, and refer to “kaffirs,” an anti-black racial slur, as “uncivilized.” (In Africa, left-wing criticism of Gandhi, evidenced by statue-toppling campaigns, is easier to come by. One Gandhi statue was removed from the University of Ghana after protests, in what a student described as “a massive win for all Ghanaians because it was constantly reminding us of how inferior we are.”)

In his work on caste, Gandhi demonstrated more sympathy for the oppressed than interest in dismantling the systems that were oppressing them. Gandhi never opposed the caste system; instead, he praised the concept of varna, the division of society into occupation-tied classes within which castes are grouped. By clearly defining social roles, Gandhi reasoned, varnas could help “prevent competition and class struggle and class war.” As B.R. Ambedkar, the author of the Indian constitution, wrote in 1945, “The social ideal of Gandhism is either caste or varna.” Ambedkar, who as a Dalit occupied the lowest position in the Hindu caste pyramid and was subject to caste humiliation throughout his life, wrote, “There can be no doubt that the social ideal of Gandhism is not democracy.” Only the complete “annihilation of caste,” as Ambedkar titled his most famous essay, could lead to any sort of truly democratic order.

Gandhi’s tacit support of the caste system was buoyed by his relationships with — and uncritical attitude towards — business magnates. Despite Gandhi’s initial skepticism of big business — he wrote in his landmark 1909 book, Hind Swaraj, that it would be “folly to assume that an Indian Rockefeller would be better than the American Rockefeller” — he developed close ties with corporate leaders. Gandhi wrote of one industrial tycoon, “May India produce many Tatas!” When the employees of the banker G.D. Birla, a longtime donor, asked to meet with Gandhi after they were physically attacked for asking for bonuses, Gandhi refused to see them. Yet Gandhi declared in 1925 that “my identification with labor does not conflict with my friendship with capital,” and separately argued that the personal accumulation of vast wealth was acceptable as long as part of it was later used for social welfare, an approach he called “trusteeship.” Gandhi felt that his conciliatory tack would avoid spooking India’s richest people with the specter of mass redistribution, and help rally them behind his cause. In some ways, Gandhi was too compromised by the enmeshed interests of Congress and industry to truly transform India’s social structures and advance real justice and welfare. As novelist Arundhati Roy has quipped, Gandhi was India’s “first corporate sponsored NGO.”

Gandhi also did more than anyone else to theologize the language of mainstream politics, which is now being weaponized by the Hindutva right. As the philosopher Divya Dwivedi has argued, Gandhi “adopted very consciously and vocally the Hindu idiom in politics.” By injecting what the historian Perry Anderson has called “a massive dose of religion — mythology, symbology, theology — into the national movement,” reappropriating religious terminology, championing traditionalist Hindu issues like cow protection, and extolling the virtues of chanting the name of the Hindu god Rama, Gandhi brought Hinduism into Indian politics and inadvertently paved the way for Hindutva’s rise. The intermingling of religion and politics is to some extent inevitable in a deeply religious country, and there is a long road between Gandhi and the BJP’s ethnonationalist project, which would have been anathema to him. But it is fair to say that by emphasizing this Hindu past, Gandhi set the stage for Modi’s government to reject the marks of pre-British Muslim colonization between the eighth and nineteenth centuries; since Modi came to power, the BJP has replaced Muslim-sounding city and street names with Hindu-centric ones. Dwivedi added, “Gandhi is the one who inaugurated the postcolonial identity, and the Hindu one, and then postcolonial as Hindu, and Hindu as postcolonial.”

While the contemporary Congress party has nominally continued to champion Gandhi’s tradition of secularism, it has not mounted a serious challenge to religious violence in modern India, from the lynching of Muslims to sexual violence against Muslim women. Elements of the party have even responded to its recent electoral losses with the deployment of so-called “soft Hindutva”policies in an unsuccessful attempt to out-Hindu the BJP — or at least claw back some votes. Some senior figures have portrayed themselves as defenders of the Hindu faith, rolling out policies subsidizing pilgrimages and displays of cow worship. Many have largely fallen in line behind the BJP’s authoritarian clampdown in Kashmir, where opposition leaders were locked up and the internet shut down for eighteen months — a stunning show of state suppression that would have horrified Gandhi, who put civil liberties at the core of his agenda. Others have equivocated on whether India is even a secular nation in the first place — as it is constitutionally bound to be. Yet as Gandhi’s party has moved steadily away from his beliefs, it continues to draw, in style and rhetoric, upon its illustrious independence-era history. The combination doesn’t seem to be selling. Congress has been soundly defeated in the last two general elections, and appears destined for a thrashing this spring. While Congress spouts lofty liberal rhetoric and quietly caves on core Gandhian principles, the BJP has set to work transforming Indian infrastructure and developing mass programs to subsidize clean cooking gas, expand low-income housing, and end open defecation. High-minded appeals to protect “the foundation of the constitution and democracy,” in the words of Congress President Mallikarjun Kharge, stand little chance against sectarian populism and a hundred million clean toilets.

It is dangerous, ultimately, to cede criticism of Gandhi to the Hindu right. Many Indians, myself included, admire our founding fathers for their grand, if imperfect and patchily implemented, vision of a secular and pluralist country. Nevertheless, the kernel of truth behind the right-wing critique of Gandhi is that the republic was founded by patrician Anglophone elites, and its core institutions do reflect the worldview of a small, affluent group who were, in many crucial ways, disconnected from the material and spiritual realities of the people they governed. Contemporary India has severe socioeconomic, caste, gender, and regional inequalities, in part as a legacy of this paternalistic cohort’s work. But that’s a starting point for politics, not a dead end. Look a little deeper, and opponents of the BJP will find not only flaws but also invaluable resources in Gandhi’s writings, particularly his distinctively Indian formulation of secularism that stands a real chance of resisting Hindutva. And in an era of rising religious violence, Gandhian pacifism itself may be more relevant than ever: it’s no longer a set of bland phrases from history books, but an urgent directive. Beyond shallow paeans to the forgotten values, Gandhi’s message could be deployed against his killer’s ideological heirs, if only someone were willing to do it. No one — politician, citizen, or intellectual — can seriously claim to inherit Gandhi’s values until they take him down from his pedestal, rescue him from both the glibness of liberal idol worship and the humiliation of Hindutva slander, and re-engage with the great thinker himself. That is surely the only fate befitting the man we once called Bapu, or Dad.