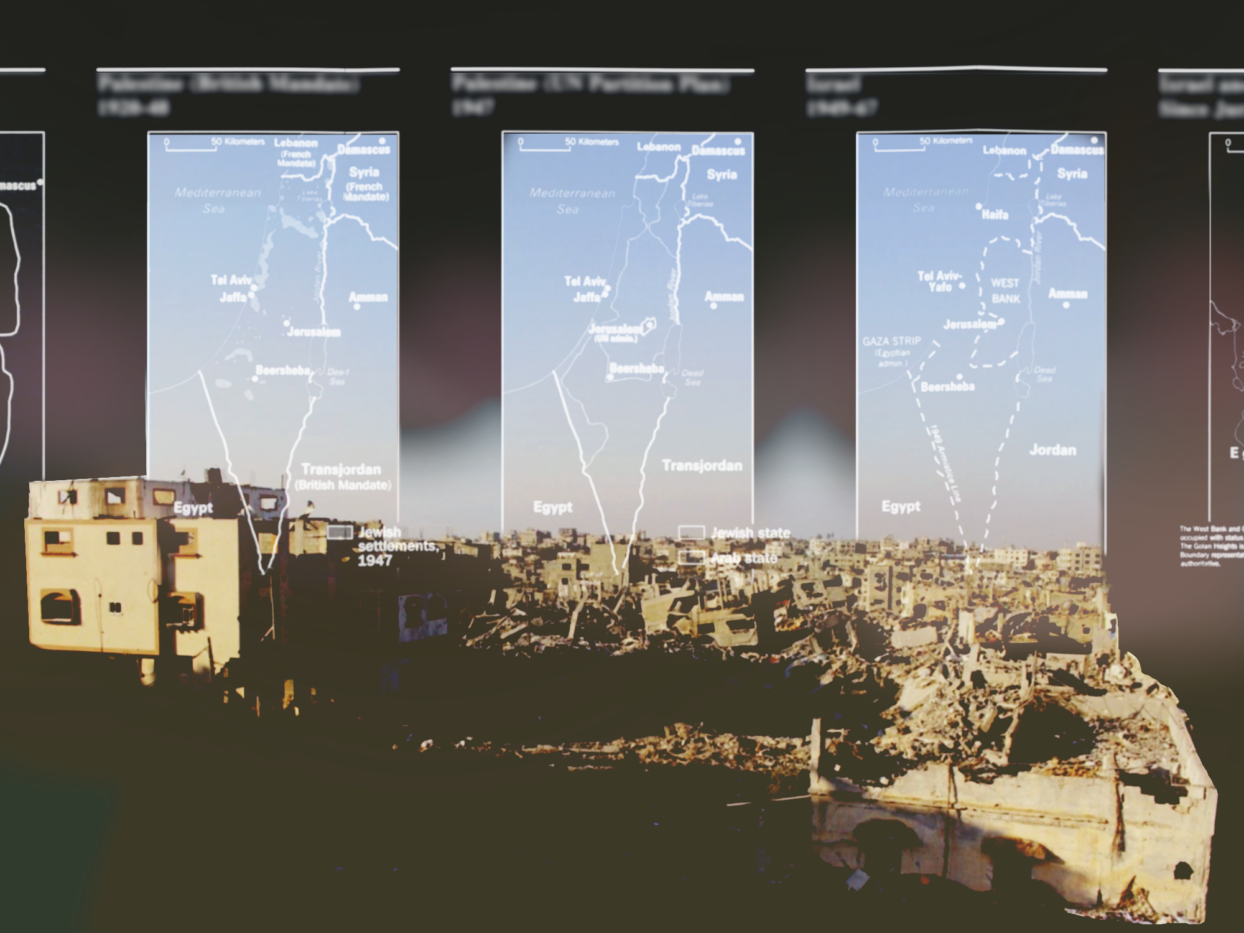

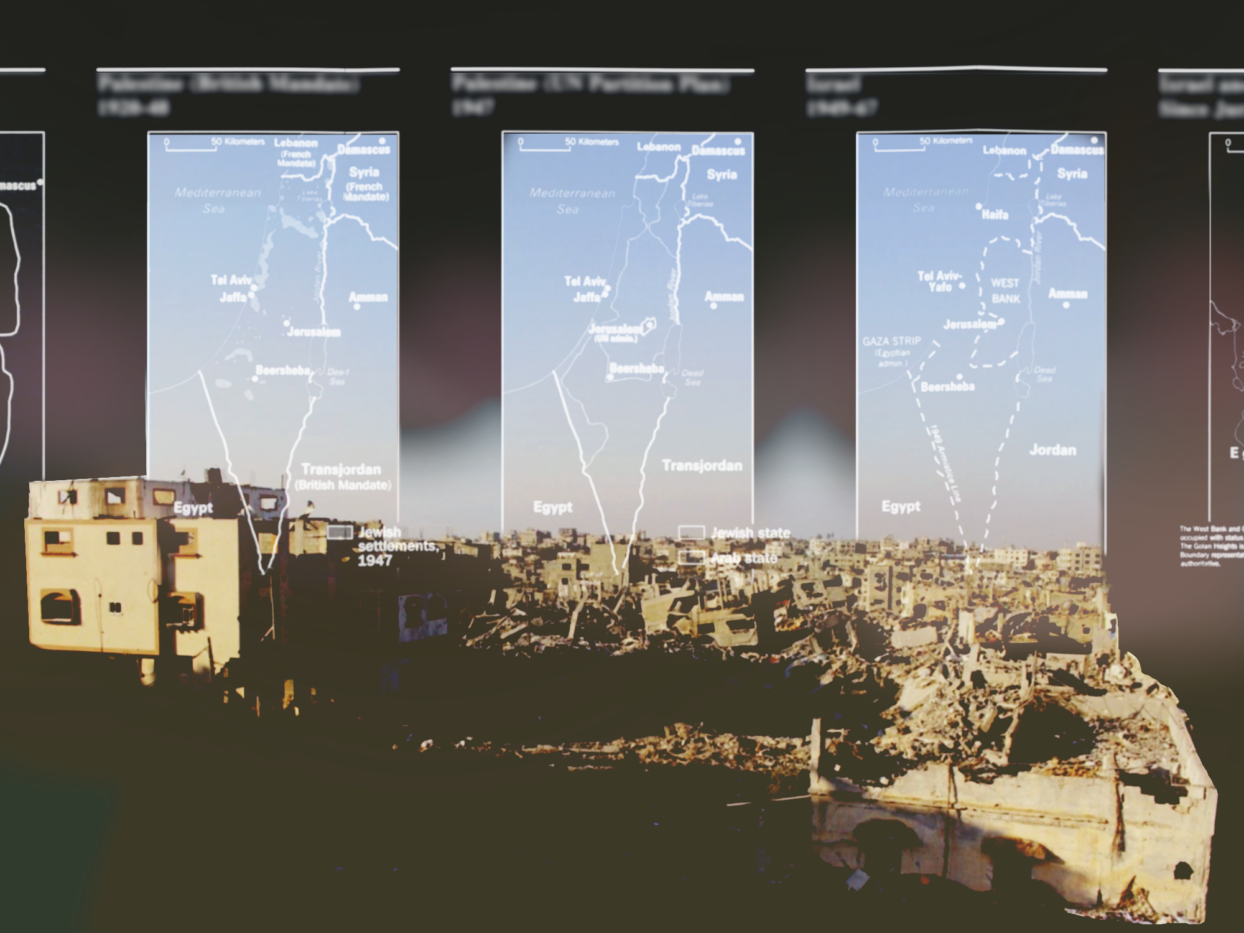

Image by John Kazior

Image by John Kazior

The image of the “fog of war,” former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara explains in Errol Morris’s 2003 documentary of the same name, suggests that “war is so complex it’s beyond the ability of the human mind to comprehend all the variables.” In this way war resembles the rest of reality — a fact that McNamara perceives dimly but often succeeds in putting out of mind. “Belief and seeing, they’re both often wrong,” he observes elsewhere in the film, as if this were an insight at which one could arrive only after years spent overseeing imperial butchery from the Pentagon. The military man’s characteristic need to see himself as outside and above normal life is capable, apparently, of exceptionalizing even fallibility itself.

McNamara’s sensibility seems increasingly to have infected the rest of us. “We kill people unnecessarily,” he avers, because “our understanding, our judgment, are not adequate.” This presumption — that the horror of war is at its heart an epistemological problem, that pointless death is a consequence of the limitations of our capacity for knowledge — is pervasive today. It has been on full display since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, and it has attained a feverish new intensity since Hamas’s massacre of some 1,400 Israelis on October 7, which included appalling crimes against civilians whose full extent we are still learning, and the genocidal military operation Israel has unleashed on Gaza in response. It lurks in every grainy video of atrocity circulated on social media: pixelated slaughter is slowed down, magnified, reversed, highlighted, and replayed. It animates the interminable debates over who is responsible for particularly horrific acts of killing. And, of course, it supplies the “humanitarian” justification for the Israeli military’s colossal, U.S.-subsidized outlays on high-tech surveillance and reconnaissance systems. Behind every Israeli cyberweapon, every glossy infographic-explainer, every fifty-tweet thread from an amateur “OSINT” (open-source intelligence) enthusiast, there is the same presumption: we could make all of this right, if only we knew.

The left, alas, is frequently complicit in this fetish of factuality. After all, its intellectuals and activists are excruciatingly aware that belief and seeing are both often wrong, as McNamara puts it. Sooner or later, every movement for social transformation must confront the problem of why so many people fail to grasp the magnitude of injustice or to perceive the power they are capable of wielding collectively. This week, watching the catastrophe unfolding in Gaza along with the stirrings of mass mobilization against further escalation, these questions have taken on new acuity. Why isn’t everyone in the street? How can people accept their government’s moral and financial support for all this horrific violence? Didn’t we learn anything from the war on terror?

For the last century, active deception has been the most common explanation for why people fail to agitate and resist to the extent we on the left would like them to. The wool has been pulled over our eyes by powerful institutions. The shorthand for this account is “propaganda,” once a relatively neutral label for state messaging, and even a self-description, as in the case of Britain’s World War I-era War Propaganda Bureau, or the Russian Marxist strategy of “agitation propaganda” (agitprop). It became a term of abuse in the interwar period. Propaganda was the preferred explanation of liberal social scientists for the rise of fascism and nationalist militarism. In the eyes of early-twentieth-century scientists, ordinary people were vulnerable to rhetoric designed to manipulate their primal emotional instincts. Citizens lived in a fog of modernity, condemned to cope with the complexity of their advanced industrial societies only through the easily manipulated representations of the press, the radio, and the moving image.

The propaganda theory lent itself more readily to technocratic than democratic politics: appointing responsible professionals to operate the machinery of public opinion seemed more realistic than systematically redressing the limitations of ordinary citizens’ social knowledge. Nonetheless, this theory also shaped the way that many on the left thought about the rise of fascism and the appeal of militarism — mainly because modern states did, indeed, churn out enormous amounts of propaganda. To many observers, propaganda also seemed to exemplify the “totalitarian” aspirations that distinguished twentieth-century authoritarian states from their predecessors. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell depicted propaganda as a regime’s chief weapon for reshaping the hearts and minds of its subjects; ever since, the left has wielded the Big Brother cudgel as eagerly as its opponents on the right and center have, often with considerable justice. In recent weeks, as surveillance and proscription of pro-Palestine sentiment have once more kicked into gear, including outright bans on Palestinian solidarity protests in France and parts of Germany, we have received another reminder that even our liberal democracies define and punish thought crimes.

In the late twentieth century, propaganda as a term moved even closer to the heart of the left-wing vernacular, thanks to Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky’s 1988 book Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. Herman and Chomsky plucked the titular concept from Walter Lippmann’s 1922 book Public Opinion, one of the quintessential statements of early-twentieth-century technocratic liberalism. Herman and Chomsky maintained that Lippmann’s fixation on propaganda and the dissemination of misleading information in the mass media could be recuperated for the cause of “radical democracy,” and generations of readers have tended to agree. Like earlier propaganda theories, Herman and Chomsky’s account benefits from the fact that it describes a real phenomenon, observable on a daily basis. It is hard to watch Anderson Cooper accidentally use the phrase “civilian loss of life” in his description of the al-Ahli hospital bombing before backtracking to omit “civilian”; or read the State Department’s new list of forbidden phrases, which includes “de-escalation/ceasefire,” “end to violence/bloodshed” and “restoring calm”; or witness a White House spokesperson retract Joe Biden’s claim that he saw photographs of terrorists beheading children (he, in fact, had not, because no such images are known to exist), and not feel manipulated, pressed onto the assembly line at the consent factory.

The same goes for that subset of propaganda known since the Cold War as “disinformation,” which has become an object of obsessive concern among American liberals since the 2016 presidential election. It is an easy target because it is real, at once inescapable and intensely obnoxious. It festers like never before on social media. The open sewer of Elon Musk’s redesigned X — with links stripped of headlines and reduced to decontextualized images, no reliable mechanism for account verification, and plainly malicious actors empowered by new algorithms — is enough to make one despair about the possibility of finding out anything accurate about an unfolding crisis ever again. The consequences were illustrated spectacularly over the past week as the world scrambled to determine conclusively who was responsible for the slaughter at the al-Ahli hospital. One post from a user masquerading as an Al Jazeera journalist who claimed to have witnessed “a Hamas missile landing in the hospital” went viral before it was discovered that the alleged journalist had spent that morning posting enthusiastically about Sydney Sweeney’s breasts. I don’t have a TikTok account, but my zoomer siblings inform me that it’s even worse over there. If online reports are to be believed, the site is currently the epicenter of a campaign by Israeli activists to pay influencers to flood social media sites with pro-Israel content.

The oppressive ubiquity of propaganda and disinformation is, however, the very reason why we must remain skeptical that they truly possess the powers ascribed to them. We believe that we are being manipulated because we feel manipulated, but that feeling is itself proof that our capacity for critical thinking is greater than the anti-democratic propaganda theorists of the interwar period suspected. If propaganda and disinformation were as effective as we are often told, one suspects that we would be told about it less — that it would not all be so obvious. Who actually trusts the media these days? Who believes everything they read online?

Before the World Wars and the rise of the propaganda theory, the left thought rather differently about the inadequacy of our understanding and our judgment. The keyword here wasn’t propaganda but rather “ideology,” a slippery Enlightenment-era concept reworked by Marx and Engels in the mid-nineteenth century. For them, the notion of ideology revealed how our consciousness is determined by what Marx called our “social being” — the relations of production and power in which each of us is caught up. Misinformation is the barrage of conflicting and occasionally fabricated evidence about the al-Ahli hospital bombing — including two posts from official Israeli accounts that attached a video purporting to vindicate their account, later deleted after a New York Times visual-investigations journalist pointed out on X that the video was from 2022. Propaganda is the habitual assertion from pro-Israel quarters in the aftermath of the explosion that the IDF “doesn’t bomb hospitals,” despite the fact that the World Health Organization has reported 62 attacks on healthcare institutions in Gaza since October 7. Propaganda is also Joe Biden’s callous quip, after making clear he believes that the explosion was caused by a failed Palestinian rocket launch and not by an Israeli munition, that Hamas should “learn how to shoot straight.” Ideology is what enables a person to regard the lives of their fellow human beings with such indifference — the appearance of Palestinian life as expendable, of Palestinian death as unserious. This ideology, like all others, is grounded in social being: the objective expendability of Palestinian life in the functional logic of American empire. To dwell in this edifice — as president, but also as a tax-paying, vote-casting subject — is to learn to tolerate the violence it systematically inflicts, one act of acquiescence at a time.

If propaganda is like a lie, ideology is like the language in which the lies are told. It is a structure of thought and of personhood, and for that reason exists behind our conscious sense of self and is relatively unresponsive to deliberate attempts to modify it. In this way it bears resemblance to the Freudian unconscious, and through it to dreams. In the shared hallucination into which we have been plunged since the al-Ahli explosion, we feel it is absolutely imperative to settle the questions of truth and falsehood at stake, in the same way that in a dream we often find ourselves convinced of the importance of some obscure objective, then find its urgency difficult to recollect upon waking. I don’t exempt myself here: I spent much of the first day after the disaster arguing online about who was culpable, explaining why I felt it made sense to assume IDF responsibility until dispositive evidence to the contrary emerged. I’ve continued to follow the proliferation of conflicting assessments by independent experts: an AP investigation concluding that an errant Palestinian missile fragment was indeed the most likely cause of the blast, as Israeli and American officials maintain; analyses from the UK’s Channel 4 News and the University of London’s Forensic Architecture research center each casting significant doubt on that narrative and, in the latter case, suggesting instead that the culprit may have been an artillery shell from the northeast, the direction of Israel.

Someday these questions may be settled beyond dispute. Last year, after an Israeli soldier shot and killed the Palestinian-American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, it took nearly four months of sustained investigatory pressure by journalists and global human rights organizations for the Israeli government to recant its initial denial of responsibility. But there is also a possibility that debate about this cluster of murders will never produce a consensus truth. When people become convinced that a moral or political debate hinges on the resolution of a particular factual controversy, consensus on the facts is often forestalled indefinitely. Israel and its allies have been posturing as if the entire critique of its military operation against Gaza and its people would be vitiated if the al-Ahli explosion had been caused by an errant Palestinian munition, which makes it almost inconceivable that they will ever back down from that claim. Conversely, many of us on the pro-Palestinian left have implicitly validated Israel’s premise by the narrowness and intensity with which we have been litigating this particular incident. The tenaciousness of the humanitarian investigators seeking to uncover the truth about what happened is admirable, but it also risks masking the reality that, were it actually true that Israel had nothing to do with the slaughter at al-Ahli hospital, the fact would remain that its military has been committing unconscionable crimes against the people of Gaza every day, in plain sight.

The tunnel vision produced by factually contested reports of evil deeds is, on one level, a clear propaganda coup, abetted by social media’s unrivaled ability to muddy the facts about more or less anything. One thinks here as well of the interminable debate about whether or not Hamas beheaded Israeli children on October 7 — a claim deployed to substantiate Israeli rhetoric analogizing Hamas to ISIS. Scrutiny of this as-yet-unproven allegation has led some on the pro-Palestinian left into a discursive trap, simultaneously appearing insensitive to the fact that children losing their heads is an unspeakable tragedy no matter the mechanism, while also distracting from the fact that even if Hamas had done such a thing, it still would not be justified for Israel to have responded by killing many hundreds of Palestinian children in return. It seems clear that the Israeli propaganda apparatus seeks actively to engender these controversies, to keep people fixated myopically on sorting through disinformation about various horror stories so that they lose sight of the larger carnival of atrocity within which these events all may or may not take place.

But this propagandistic strategy succeeds because of the ideological soil into which it sinks its roots: because of the dream we share, in which we find ourselves enveloped in the fog of war, laboring under the fantasy that we could secure peace if only we could discover a way to dissipate the murk. Here, as always, ideology serves as an imaginary representation of our real social relations. In this case, we have reflected in dream logic the reality that the war machine of the American empire and its client states is totally insulated from political oversight and democratic control. American military support for Israeli apartheid has an inertia that makes it impervious to the value judgments and moral convictions of ordinary people. A recent CBS News/YouGov poll found that a majority of Democrats oppose sending additional weapons to Israel, but few honestly expect this reservoir of discontent to make any difference: all but a handful of Democratic elected officials, all the way up to the President himself, have signaled their intention to move more or less in lockstep to pour ever more American weaponry into the IDF’s arsenal.

Since our values so palpably don’t matter, we take refuge in imagining war as a kind of deadly board game, governed by objective rules that obviate the need for political debate. There are certain unquestionable premises: Israel has a “right to defend itself,” limited only by a canon of “laws of war” that distinguish acceptable from unacceptable killing. Compliance with these laws is a purely factual question, in a sense value-neutral: anyone, whatever their other commitments, ought to be able to agree that certain acts are “war crimes” and therefore intolerable, while other massacres are lawful and therefore beyond reproach. This fantasy restores to us some of the power stripped by the depoliticization of war: if we can penetrate the fog of war and prove objectively that something happened that was against the rules, we might still be able to make a difference, to arrest the progress of the catastrophe that provokes in us such impotent moral outrage.

The unreality of the dream that factual clarity will bring all these war crimes to an end is demonstrated every day. It is demonstrated every time the Israeli government states, without apology, its intention to punish Palestinian civilians for the crimes of Hamas; every time the IDF bombs, without denial, a school, a refugee camp, or — yes — a hospital (such as Gaza’s al-Durrah Children’s Hospital, which, according to the Palestinian health ministry, was evacuated after being targeted with white phosphorus bombs, which Human Rights Watch considers illegal in civilian areas); every time the sun rises on another day of illegal occupation. It was demonstrated when the Israeli military’s eventual admission of responsibility for the murder of Shireen Abu Akleh did nothing to alter the United States’s unconditional commitment to “standing with Israel.” It will be demonstrated again and again when the IDF’s anticipated ground invasion of Gaza commences, just as it was demonstrated during its last ground invasion, in 2014, after which the U.N. found evidence of “serious violations of international humanitarian law and international human rights law by Israel and by Palestinian armed groups.”

We need to recognize this dream that grips us as a nightmare — to allow ourselves to appreciate the full grotesquerie of what we have found ourselves doing: poring endlessly over photographs of human corpses, trying to ascertain, as objectively as possible, how the dead babies we see before us lost this or that appendage. From this nightmare there may be no awakening, but as courageous protestors in the streets around the world have shown us this week, it is possible at least to scream, to let the horror in which we are drowning enter our lungs and to expel it back with force at the butchers who have compelled us to accept the rules of their game. Then we may begin to weave together a new dream, a dream of Palestinian freedom and of peace with justice.

Erik Baker is a lecturer on the history of science at Harvard University, an associate editor at The Drift, and the author of Make Your Own Job: How the Entrepreneurial Work Ethic Exhausted America.